John Singer Sargent’s Essence in a Brushstroke

Though it offers little in the way of Sargent’s artistic engagement with the city he called home for a decade, “Dazzling Paris” is a reminder of his uncommonly skillful brushwork.

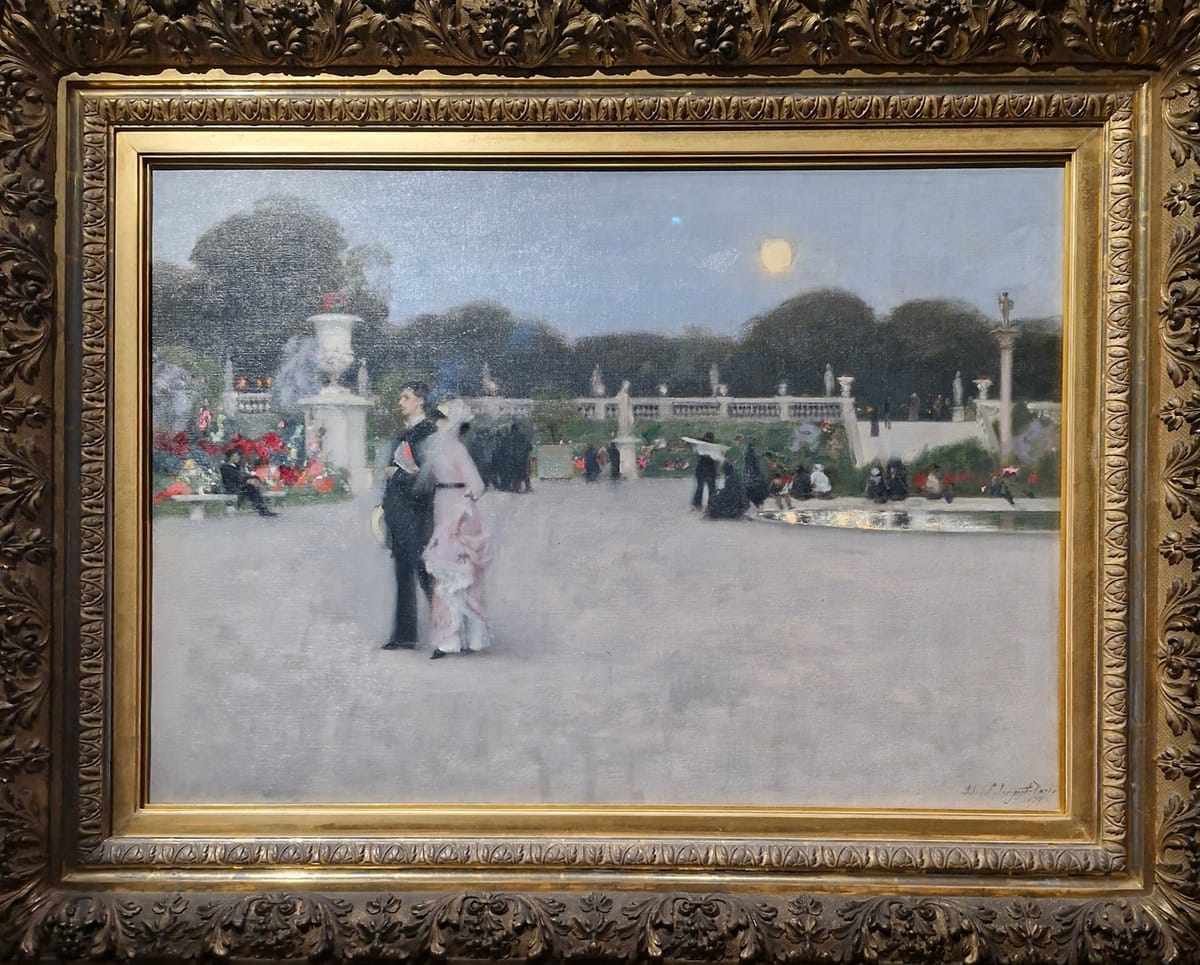

PARIS — Despite having lived and worked in Paris for roughly a decade, John Singer Sargent is difficult to pin to the city in discernible artistic ways. The peripatetic painter’s portrait subjects are as geographically scattered as his own travels across Europe, where he was raised by American parents. For John Singer Sargent: Dazzling Paris at the Musée d’Orsay, the curators set themselves quite the challenge in gathering works linked to his time in the city from 1874 to ’84 and, apparently, beyond, noting in the wall text that “Parisian subjects feature surprisingly little in his work.” One small study from 1879 of the Luxembourg Gardens near his studio, on view in the exhibition, is notable for being so incidental.

Dazzling Paris opened in September on the heels of two recent major shows: Sargent and Fashion at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and Tate Britain, and Sargent and Paris at the Metropolitan Museum of Art — whose curator Stephanie Herdrich co-organized this show at the d’Orsay. However, the artist still remains relatively obscure in France. The curators claim this to be the first monographic show by any French museum.

Before inevitably opening out into Sargent’s speciality — large scale, fabulously painted society portraits — the exhibition opens with two smaller chambers. One is a travelogue of sorts, containing en plein air sketches of vistas reflecting his extensive travels around wider France, Italy, Spain, and Morocco; the quaint oil painting “Atlantic Sunset” (1876–8) or a portrait of his pal “Ramón Subercaseaux in a Gondola” (1880) in Venice. The wall text stubbornly shoehorns in Parisian references, stating under the room’s title, “Sargent, Paris and the World,” that these were brought back to the city and used as aides in his studio for the “ambitious compositions that he showed at the Salon,” hijacking each work’s singular creation for the sake of this argument.

The next room, however, contains some of the scant surviving pieces from Sargent’s earliest days in Paris, made in 1874 during his apprenticeship French painter Carolus-Duran’s studio. Far more aptly than his famous society portraits and any subject matter explicitly relating to Paris or even France, the contrast between the two utterly polarized styles demonstrates why Sargent is such a superlative pan-generational and pan-geographical talent. On the one hand, we have rare academic drawings he produced at the Accademia di Belli Arti in Florence, such as his 1873–4 study of the Dancing Fawn antique statue in the Uffizi. It is a masterclass in finely rendered, smoothly modelled grisaille with effortless foreshortening, shadowing, and tone. Similarly, the smooth marble rendered in 1877 “Drawing of Ornaments” is so astoundingly accurate and shaded as to resemble a computer-generated design to my modern eyes.

John Singer Sargent, "Drawing of Ornament" (1877) (left) and "A Male Model Standing before a Stove" (c. 1875–80) (right), both oil on canvas

Yet placed immediately adjacent is “A Male Model Standing before a Stove” (1875–80), an oil study calling to mind kitchen-sink realism. Here Sargent built three-dimensionality by constructing faceted layers, as opposed to capturing smooth antique marble in one uniform surface layer built up simultaneously. Even the surface colors are manipulated by the rough, impasto preparation of the ground underneath. Technically, he can do it all.

Take the other studies he made during his travels to Madrid's Museo del Prado and the Netherlands — specifically which artists drew his eye. Dazzling Paris includes his 1879 copy of Diego Velázquez’s “The Jester Calabacillas” and 1880 copy of the standard bearer from Frans Hals’s “The Banquet of the Officers of the St. George Civic Guard.” What all three painters have in common is an academic ability to capture life as accurately as possible, faithfully and with crisp, finely tuned shadowing. That innate, confident ability allowed them to economize their brushwork to the absolute bare minimum in their own paintings. Mature works by all three are characterized not by solid built-up layers of oil paint, where all of the thing is modeled completely, but by only the barest essential strokes giving an overall visual impression. Go up close to look at the brushstrokes of Sargent, Hals, and Velázquez in isolation and see that their people, furniture, and objects are constructed seemingly from nothing, with bare canvas boldly showing through. The collection of brushtrokes in Sargent’s “Rehearsal of the Pasdeloup Orchestra at the Cirque d’Hiver” (1879–80) indeed feel like parts of a hanging mobile that have just drifted into correct position.

In short, the d’Orsay has demonstrated the magnificence of Sargent’s painterly ability on a level with Velázquez and Hals in the very first room, and we haven’t even gotten to his society portraits yet. Must French visitors then be convinced of his greatness through his relevance to their own country? Posited as the central portrait representing a key Parisian event in Sargent’s life is his 1883–84 depiction of socialite Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, known as “Madame X,” on loan from The Met. Joined here by an additional unfinished copy loaned from the Tate, this is its first showing in Paris since the moral scandal it caused at the Salon in 1884, the fallout from which likely precipitated Sargent’s move to London two years later. Such stark treatment of this woman of society upturning her nose in profile away from us, pale white skin contrasting with daring plunging black gown (originally with one fallen strap, later reinstated), was far too sexy and scandalous for the Parisian art world. Compositionally, its simplicity and tonal contrast have more in common with the work of his fellow American artist James McNeill Whistler, and the brushwork itself is far from Sargent’s most dazzling.

Beyond this centerpiece, the plethora of society acquaintances Sargent painted are always immensely pleasurable for their sheer bombast, and there is an abundance to enjoy here. It has clearly been difficult to pull together a sense of how Sargent may be definitively aligned with Paris, and we should give ourselves permission to celebrate the paintings for what they are. In this sense, the exhibition title is perhaps less a reference to the way Sargent dazzled Belle Époque Paris than a reflection of the curators’ intent to dazzle the Paris of today.

Sargent: Dazzling Paris continues at the Musée d’Orsay (1 Rue de la Légion d'Honneur, Paris, France) through January 11. The exhibition was curated by Caroline Corbeau-Parsons, Paul Perrin, and Stephanie Herdrich.