Nicola L.’s Soft Power

The late artist’s playful “functional sculptures” nod to second-wave feminism, but make a broader statement about resistance through collaboration.

BOLZANO, Italy — In the opening space of Nicola L.'s I Am the Last Woman Object at the Museion, the late artist’s fabric banners hang from the walls. Emblazoned with stenciled slogans like "We Want to Breathe" or "Same Skin for Everybody," each has head-shaped spaces big enough to contain the faces of multiple people who might slip into these skins, serving as a testament to solidarity.

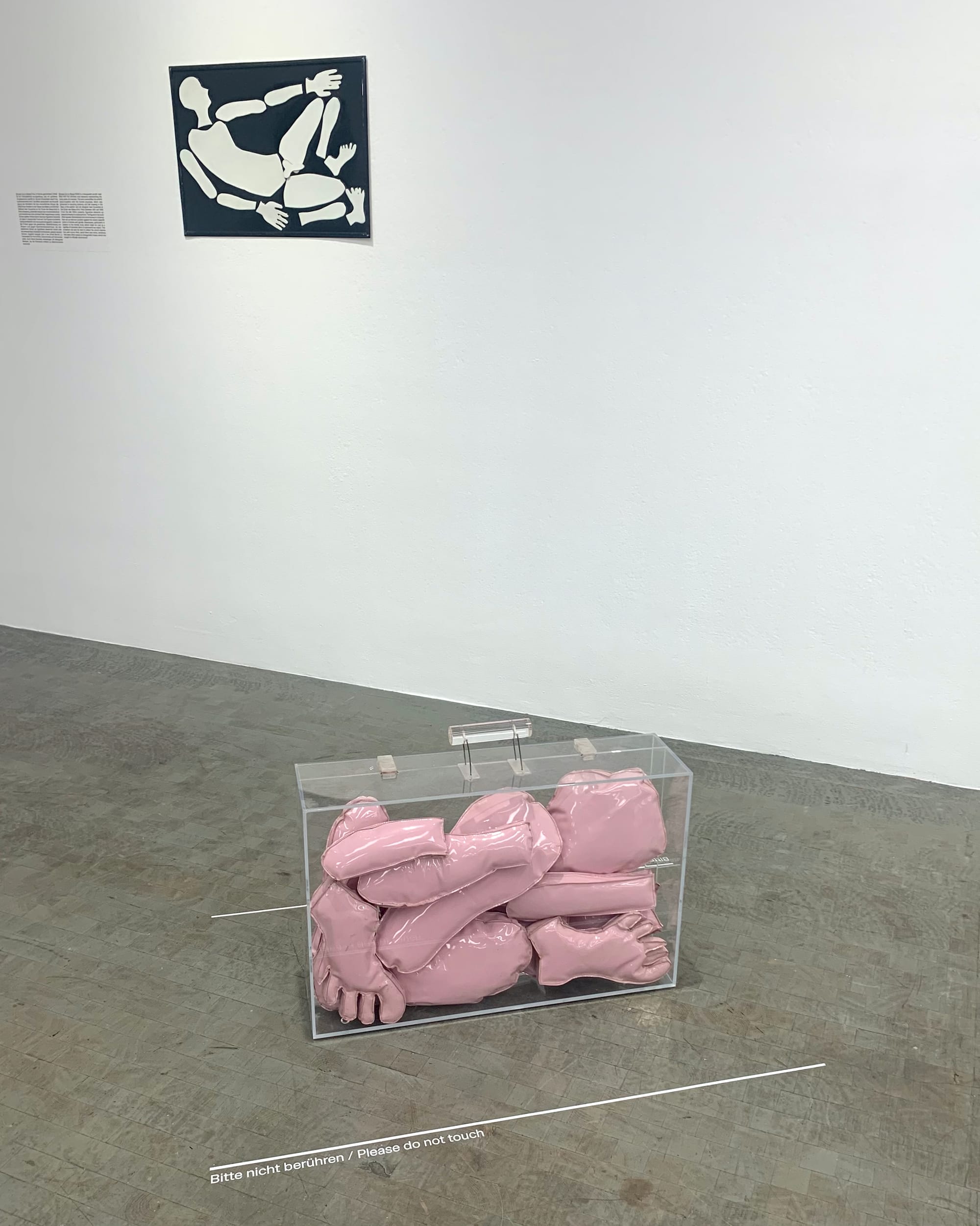

Morocco-born French artist Nicola L. (full name Nicola Leuthe-Lanzenberg) worked between Paris and Ibiza starting in the 1960s, producing art loosely aligned with Nouveau Realism: think Niki de St. Phalle, Yves Klein, or Jean Tinguely — playful pieces embedded with social commentary. Her later “functional sculptures” — among them the Femme Commodes (1969–2014), brightly colored wooden cabinets shaped like feminine silhouettes, with drawers occupying breasts, bellies, or navels — nod to second-wave feminism. Her furnishings include a large vinyl floor cushion in the shape of a foot, a sofa whose backrest traces a facial profile, and even lamps designed as popped-open eyes or red lips.

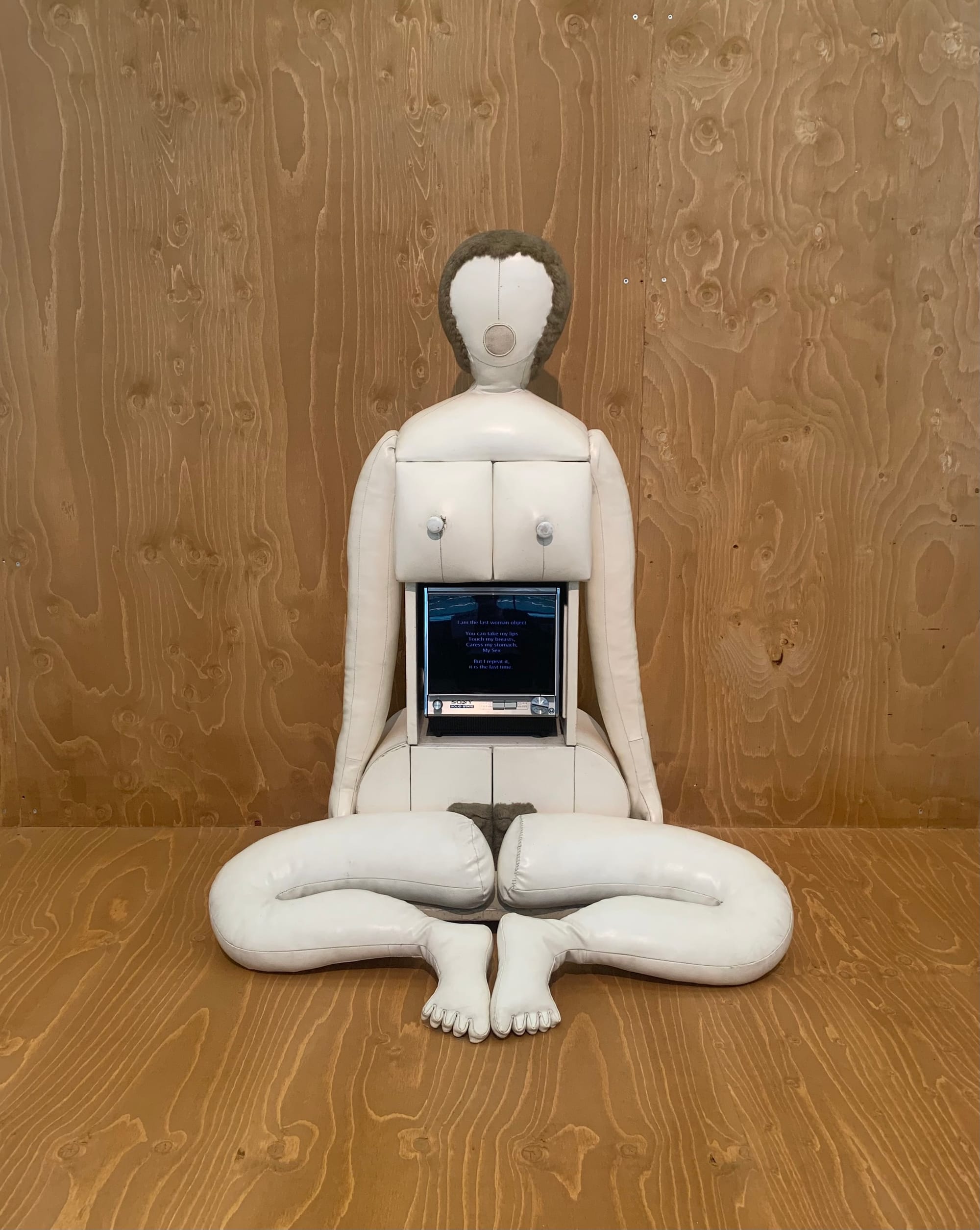

She ultimately landed in New York in 1979, where she moved into the famed Chelsea Hotel and befriended artists like Claes Oldenburg, Carolee Schneemann, and Marcel Broodthaers. In the 1970s she sent groups into public spaces in her “pénétrables” (wearable textile garments or environments), such as “Red Coat” (1969), a red raincoat for 11 people to wear at one time. Public performances in this coat, and one in blue, would continue until her death. Another iconic pénétrable is “Fur Room” (1969/2020), a womblike freestanding space lined with purple fur and containing body-shaped receptacles into which viewers could zip themselves. In fact, the body is everywhere in her art — her collages, drawings, and two-dimensional works delineate feet, heads, and hands. From 1977 until well into the 2000s, she made documentaries of the subculture, creativity, and resistance around her, recording musicians at CBGB’s in New York or activist Abbie Hoffmann, for example. Named after an eerie soft vinyl sculpture in the shape of a woman, with a television screen as a belly, the exhibition speaks to an itinerant life of subtle resistance to the status quo, a commitment to counterculture, an exploration and celebration of embodiment, and a “delirious” (in the words of the artist) optimism.

This is the last station in a traveling exhibition organized by Nicola L.’s estate and initiated by London-based Alison Jacques gallery. It originated at London’s Camden Center and went on to Frac Bretagne in France and Kunsthalle Wien in Vienna before reaching Bolzano. Gorgeously designed by Berlin-based Manuel Raeder, this Italian leg is the largest and most comprehensive. Spread across two floors and bathed in natural light, the artist’s work can truly breathe.

In late summer this year, I saw the slightly less expansive (but still impressive) Viennese iteration, titled simply Nicola L., without knowing much about the artist, and was stunned at how relevant her work remains today. In Bolzano, I toured the show with her son, Christophe, and grandson, Oliver. I mentioned to Oliver that his grandmother’s works could easily be used in protests and demonstrations today. Why hadn’t I heard of her? Nicola L., like so many boundary-pushing women artists of her generation, hadn’t been canonized — her first institutional survey ran at New York’s Sculpture Center only in 2017, a year before her death, and her first monograph was published in 2023.

It’s common knowledge that in the past decade or so, many women artists, often active in the 1960s and 1970s, hit big with international museum shows only in their later years, or posthumously — even if a handful of them, like Nicola L., had moments of early success and were connected to influential art networks. Other European artists, such as the late Geta Brătescu, Maria Lassnig, and Birgit Jürgenssen, were all canonized long after their heydays: Brătescu’s bold drawings, performances, collages, and quirky sculptures only became widely known after her appearance in the 2017 Venice Biennale’s Romanian pavilion. Her writings, on the solitude of the studio, working as an artist under a repressive Communist regime, and simply being a woman, are breathtaking. (Full disclosure: I copyedited Apparations, the book accompanying her Venice appearance — and the writing was so exquisite that I did not want the job to end.) Austria-born Lassnig painted self-portraits that shivered in pastels and encapsulate the inner turmoil of being a woman in the world; her later work unabashedly depicts living in an aging body. Though she was known in Europe, she had less of an international profile and died in 2014 at age 94, just two months after a solo survey opened at MoMA PS1.

Jürgenssen, who died in 2003 at age 54, and whose multimedia oeuvre was underexposed in her native Austria during her lifetime, gently critiques the rigid patriarchal structures that still linger there; her contemporary, Valie Export, was far more visible and outwardly provocative. Jürgenssen’s subtle and varied work only gained traction in the early 2010s with the publication of multiple monographs and broader exposure. Then there’s Rome-based Isabella Ducrot, now in her mid-90s. After decades of production, her intricate textile works and paintings, which she started producing in her 50s, are only now featured as catwalk backdrops at Dior, and represented by blue-chip galleries such as Sadie Coles HQ in London, Petzel in New York, and Gisela Capitain in Naples and Cologne.

While this late recognition obviously has to do with the history of structural invisibility for women, its market-driven aspect is less often acknowledged. Under-recognized artists tend to have troves of unsold inventory that dealers are keen to promote and sell. But another, more hopeful, reason that Nicola L. and others are finding such strong resonance in the 21st century is that this work seems, perhaps, even more relevant now than when it was made — it represents a more feminine, dare we say more erotic (in Audre Lorde's sense), approach to navigating a difficult world in which forceful resistance to abuses of power only seems to add fuel to toxic fires. In her catalog essay, Museion curator Leonie Radine cites Nicola L.’s “soft resistance” to the issues of her time (civil rights struggles and opposition to the Vietnam War among them), and it’s true — despite their often plush or whimsical materiality, her art invites collective action, demands embodiment, and maintains a certain levity or even joy.

We have something to learn from strategized soft strength, right here, right now. And the best artists are often canaries in coal mines: They divine the future — which, in the end, just might be female.

Nicola L.: I Am the Last Woman Object continues at the Museion (Piazza Piero Siena 1, Bolzano, Italy) through March 1. The exhibition was curated by Leonie Radine with curatorial assistant Mette Zannato.

Editor’s Note: Some travel for the author was paid for by the Museion, Bolzano.