Lotty Rosenfeld Weaponized the Line

The Chilean artist knew that survival under authoritarianism requires both sustenance and nerve — something to live on and something to stand for.

Disobedient Spaces at Wallach Art Gallery approaches Lotty Rosenfeld’s work through the slight deviations that, when repeated, begin to shift the political ground beneath an authoritarian regime. Born in Santiago, Chile, in 1943, Rosenfeld came of age under conditions that made such interference urgent. Her most iconic action, “Una milla de cruces sobre el pavimento" (One Mile of Crosses on the Pavement, 1979), was first carried out on Avenida Manquehue, and later across the presidential palace in the early years of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship. She attached white tape and bandages onto dashed traffic lines, transforming them into a trail of accumulated crosses.

Grainy black-and-white footage follows Rosenfeld's slow processional march, her body bending forward to inscribe a disobedient line. The marks read sequentially as a tally — one that adds up the dead, the disappeared, the state’s sanctioned silences. But it is also an improbable insistence that something additive and charged with possibility might still emerge from the negative. Rosenfeld repeated the action throughout the 1980s and beyond, from the Atacama Desert (March 1981) to outside the White House in Washington, DC (June 1982), letting the line migrate across sociopolitical contexts while retaining its unruly charge.

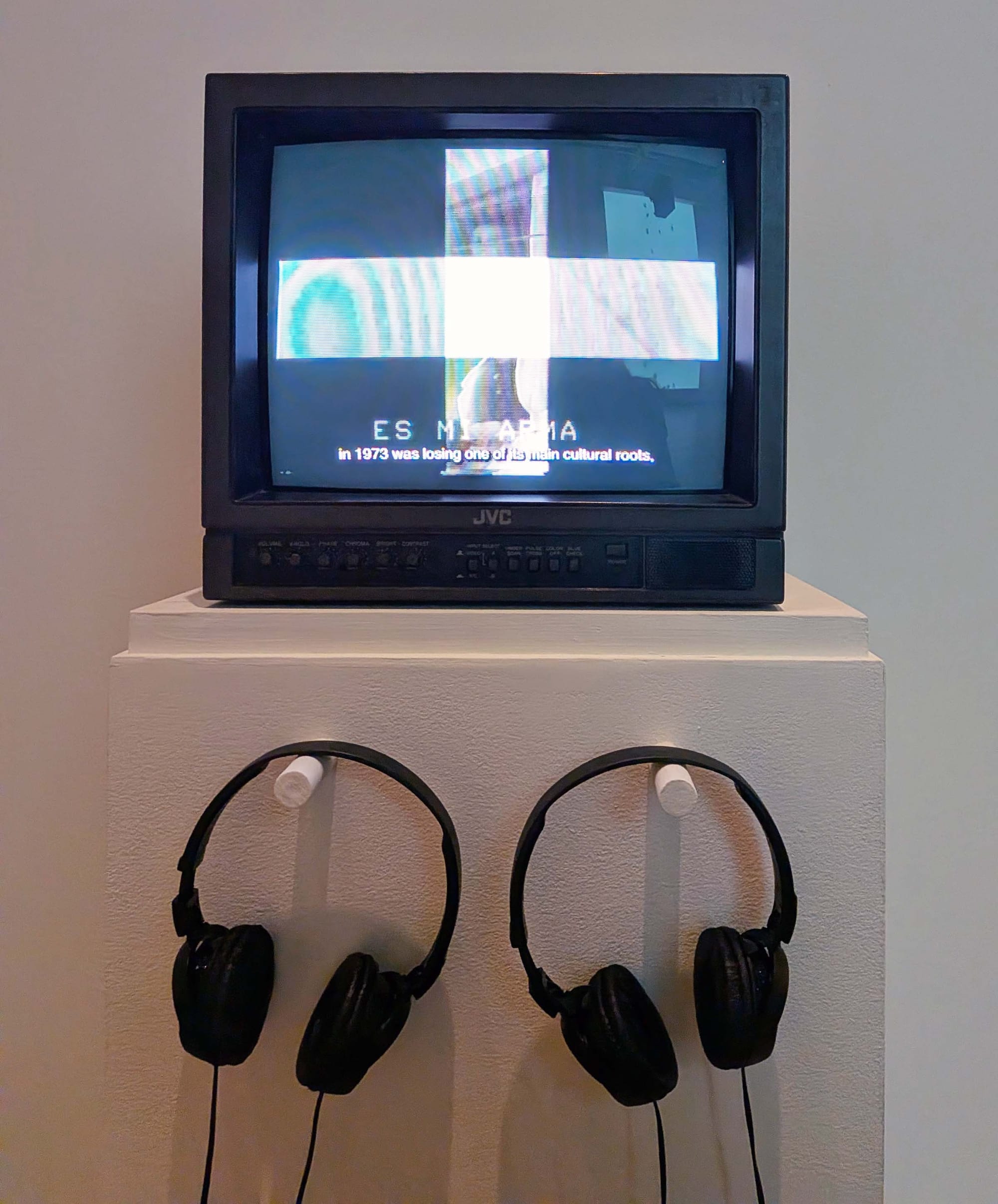

The line that is made to misbehave shows up across many works, like in the video “I - +” (1987), in which a horizontal band plays footage of her street crossings, slicing through a vertical column of state-controlled broadcast — including Pinochet rallies and Reagan-era posturing — to form a luminous cross. On a small TV monitor, the split screen reads as a quiet hijacking of the state’s visual field, punctuated by the intermittent scroll of the phrase “Esta línea es mi arma” (This line is my weapon), a caption that names Rosenfeld’s register of breach.

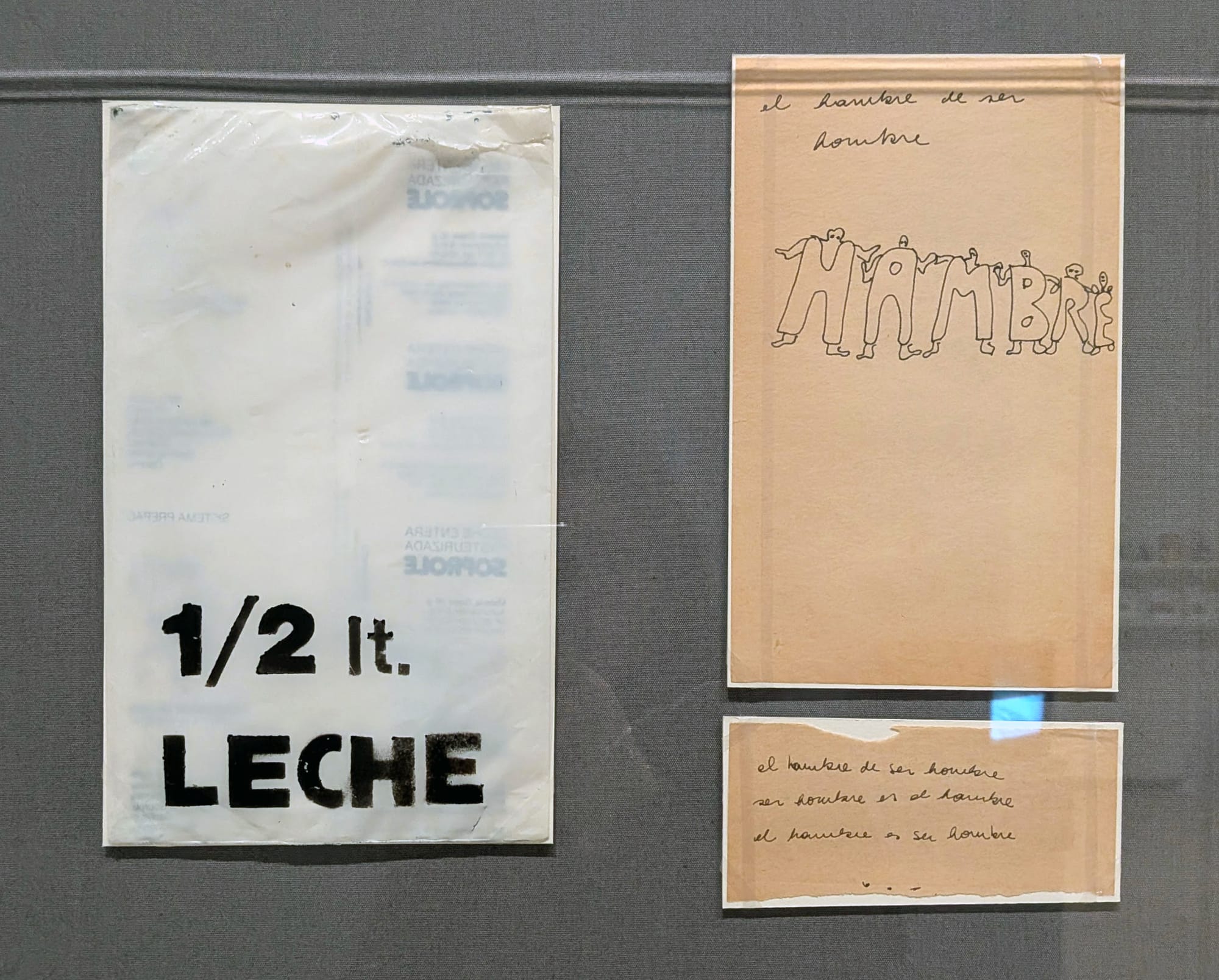

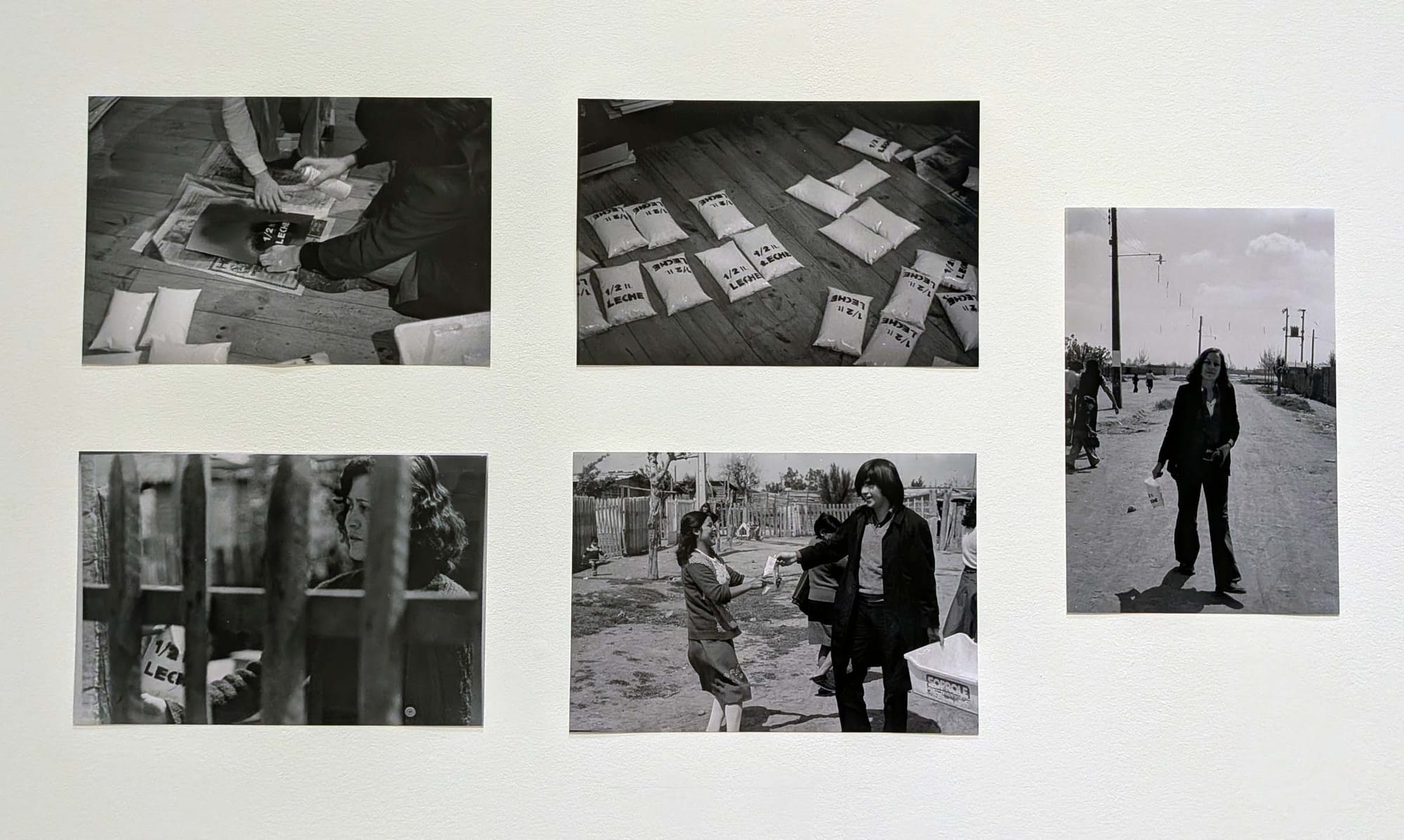

Disobedient Spaces emphasizes the networks of exchange and mutual support that shaped Rosenfeld’s practice. Moments when Rosenfeld worked alongside Cecilia Vicuña and writer Diamela Eltit situate her within a network where activism and poetry were mutually sustaining. Archival posters, pamphlets, and correspondence document Rosenfeld’s work as a founding member of Colectivo Acciones de Arte (CADA), including "Para no morir de hambre en el arte" (How not to die of hunger in art, 1979), when the group redistributed bags of milk in low-income neighborhoods of Santiago. Milk carried particular weight in Chilean public life. It was central to Allende’s nutrition programs, and under Pinochet’s dictatorship, it transformed into a marker of scarcity and a symbol of the rapid dismantling of social welfare.

CADA coordinated further actions across the city, from a procession of milk trucks to full-page newspaper ads and interventions at cultural institutions, eventually sealing 100 milk bags and a manifesto inside an acrylic box, to be reopened only when the public regained access to their unmet basic needs. The title “How not to die of hunger in art” might read at first as a familiar problem of artists’ precarity, but it signals that survival under authoritarian rule requires both sustenance and nerve — both something to live on and something to stand for.

For CADA, that meant refusing to let artistic discourse remain insulated from the social urgencies surrounding it and instead moving directly into the street — inviting participation, unsettling routines, and demanding visibility. This is most clearly seen in the national spread of the NO+ (“No more”) campaign, a slogan designed to be completed by citizens with their own demands and circulated across Chile through collective use. The exhibition echoes this distributive spirit by offering reprinted flyers and small NO+ pin — objects that demonstrate how the work gained force by being passed hand to hand.

Across these works, what emerges most forcefully is that Rosenfeld’s resistance was never simply oppositional, but built on collective methods. Her actions slipped past the state’s mechanisms of control, carving out fissures where dissent could take root, and making visible how disobedience often begins with the smallest breach: the refusal to let a line point only in one direction.

Lotty Rosenfeld: Disobedient Spaces continues at Wallach Art Gallery (615 West 129th Street, West Harlem, Manhattan) through March 15. The exhibition was curated by Natalia Brizuela and Julia Bryan-Wilson.

Editor's note 1/20/26 1:30pm EST: A previous version of this piece stated that “Una milla de cruces sobre el pavimento" (One Mile of Crosses on the Pavement, 1979) was first carried out across from the presidential palace. It was first performed on Avenida Manquehue, and later across from the palace.