Reexamining Picasso's Politics

Legend has it that Pablo Picasso was a lifelong Communist. But, as it turns out, it was more complicated than that.

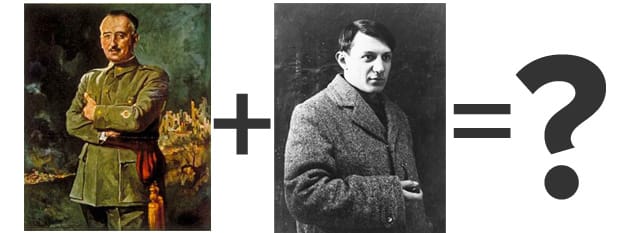

Legend has it that Pablo Picasso was a lifelong Communist. The man who painted “Guernica” (1937) is known for having been anti-Franco, anti-fascist, and possibly even something of a political activist. But, as it turns out — and not surprisingly — it was more complicated than that. Picasso, in fact, spoke with representatives from Franco’s regime and considered having a retrospective of his work shown in Francoist Spain.

Evidence of these conversations, which happened around 1957, has been discovered by art historian Genoveva Tusell Garcia, who wrote up her findings for The Burlington Magazine earlier this year. The article is behind a paywall, but a piece by Jonathan Vernon in the New Statesman lays out the charges as follows:

Although the [Franco] regime’s prevailing attitude toward Picasso was one of hostility, certain of its members came to see an advantage in taming his reputation and sharing in his achievements. In 1957, they approached the painter to discuss the possibility of his work returning to Spanish collections, and even a retrospective.

What is extraordinary is not just that Picasso took part in these talks, but that he provisionally agreed to their terms. ‘I hope Franco lives longer than I do’, he said, before referring ‘with a mixture of stubbornness and sadness’ to his political stance as an obligation.

Further digging leads to a 2010 New York Review of Books article by John Richardson, Picasso’s biographer, who paints a fuller picture of the situation (worth reading in its entirety). The artist, it seems, wanted a retrospective in his native Spain “above all,” Richardson writes, one “that would accord him a similar status [to Velázquez and Ribera, Góngora and Calderón].” Meanwhile, for the Francoists, “Guernica” “had become a crucial problem.” So in 1956, someone was dispatched to offer Picasso a retrospective in Spain. This was an offer difficult to completely turn down. After much back and forth, as well an information leak and the start of some rumors, “the artist concluded that a Franco-backed exhibition would shatter his image and amount to a victory for fascism.” Whew.

Every so often, revelations come along that change our perceptions of an iconic artist; see, for example, Joseph Beuys and his ties to the Nazis. But rather than go for bombast — no, Picasso was not a Franco collaborator — it’s much more useful to look at these new pieces of history as rounding out the pictures we have, chipping away at the artistic myths. To his credit, Vernon argues for this approach in the New Statesman, as Richardson did three years ago in the New York Review of Books. Picasso, it seems, was neither a Communist activist nor a fascist sympathizer; he was, rather, a human being.