The Hallucinogenic Origins of Art

A paper published in the most recent issue of Adaptive Behavior significantly updates the long-standing thesis that the global prevalence in prehistoric art of "certain types of geometric visual patterns" suggests hallucinogenic inspirations. The University of Tokyo authors — Tom Froese, Alexander W

A paper published in the most recent issue of Adaptive Behavior significantly updates the long-standing thesis that the global prevalence in prehistoric art of “certain types of geometric visual patterns” suggests hallucinogenic inspiration. The University of Tokyo authors — Tom Froese, Alexander Woodward, and Takashi Ikegami — conclude that this theory is largely correct, and go on to map specific neurobiological features to specific forms of geometric abstraction.

“[H]uman symbolic practices and their meanings are the historical outcome of a seemingly open-ended social process of cultural evolution,” they write. But the scholarly community in cognitive science is split among those who believe that there exists an internal “symbolic system” and those who hold that there is a “cognitive gap” between basic, adaptive behavior and more abstract forms of human cognition. The former school of thought is held to be the older, more “traditional” view — but the lead author, Tom Froese, has been active in advocating for the latter, what he calls the “enactive approach.”

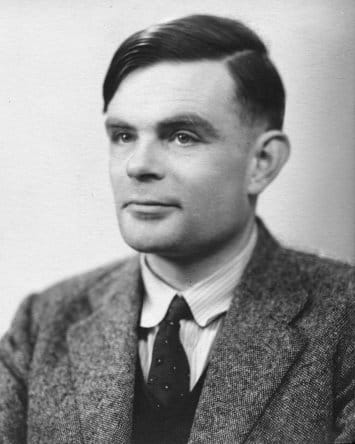

The scientific study of the geometric faculties of the human brain dates back to the 1970s, and the authors spend a great deal of time engaging the scholarship stemming from something called the Turing mechanism, which comes from a paper published by the late mathematician Alan Turing in 1952. Turing’s paper, completed shortly before he took his life, provides a model for the formation of complex geometries in nature (there’s a great Wired slideshow explaining the gist of his findings if Turing’s complex proofs aren’t quite your speed).

Froese et al. then proceed to dismantle a handful of theories relating to the appearance of geometric forms in art, most notably an established scholarly view that “social conflict and class struggle” were the primary drivers of the first symbolic artworks. They return to Turing’s idea of natural cell assemblies forming certain geometries to explain the “selective bias” of the first artists throughout the world for certain types of shapes, suggesting a common neurobiological state. In other words, the authors remain convinced that hallucinogenic altered states, shamanic or otherwise, likely played a significant role in mediating the transition from “here and now” basic motor functions to refined visual practices — the first geometric art — by “decoupling” the mind from the survival-oriented mentality driven by the immediate environment.