The Internet According to Sex Workers and Cyberfeminists

Mindy Seu’s "A Sexual History of the Internet" is part performance, part artist book, and part financial experiment.

In A Sexual History of the Internet (2025), artist and researcher Mindy Seu proposes a different kind of archive: one that maps how bodies, desires, technologies, and systems of power have been entangled since the earliest days of our beloved web. Rather than frame this research through a traditional academic text or media theory, Seu retools the publishing format entirely, intentionally delivering the project as part performance, part artist book, and part financial experiment. Taken together, these components challenge the sanitized, teleological narratives that have long defined internet history. In their place, Seu offers a parallel record drawn from theorists, net artists, cyberfeminists, and sex workers — those who shaped the internet from the margins, often through websites, chat systems, forums, and cam networks used to advertise their services. These figures, whose contributions to online culture remain widely overlooked, become central to Seu’s retelling.

“The Internet developed from a military-industrial complex so it’s no wonder that it has a fraught relationship with sexuality,” Seu explains. “A clear through line between the military and sex is power.” There are indeed obvious power imbalances in early web culture, where many expressions of online sexuality were extractive — marked by stolen images, chatroom misogyny, and techno-utopian fantasies projected onto fembots and cyber-babes. “Women were the first ‘computers’ after all,” Seu notes, “they pushed forward the development of new technologies, from chatting, personal websites, cryptocurrencies, and the like.”

Part of what makes Seu’s work so resonant is her approach to narrative hierarchy. The book draws attention to dominant cultural milestones in computing — ASCII porn, the first JPEG pulled from a Playboy centerfold — while advancing lesser-known stories with equal weight. “Some of those more marginal histories have been published before, and some were told to [Mindy] in bars or book events or in her classrooms,” shares the book’s editor, Meg Miller. “She’s diligently gathering these stories, connecting them, and surfacing them to a wider public. She’s doing this in a way that is artistic, accessible, and legitimizing.”

The work began as a lecture-performance that Seu prototyped with collaborator Julio Correa in 2023, the same year she published the Google-Spreadsheet-turned-manifesto Cyberfeminism Index. The performance of A Sexual History animates Instagram Stories into a delivery device. At sold-out venues spanning Antwerp, New York, Oslo, and Madrid, the audience sits in a dark room with no central screen or podium. They navigate to the finsta profile, @asexualhistoryoftheinternet, from their own phones. Seu weaves between the seats, reading the script aloud as the stories play out on each device. “The lecture-performance was the primary vehicle,” she shares. “It was a way for the audience to reconsider their ubiquitous tools (like phones, or apps) and treat that as an entry point into their larger histories.”

The immersive, distributed performance evolves into a shared experience quite unlike any other. “The techniques she employed were so delightfully meta,” shares artist Ani Liu, who participated in a panel with Seu at SXXTXCH LIVE in New York. “Synchronizing all the bodies in the room to a social media platform, where carefully researched knowledge was dispensed through a medium which could be considered an intimacy technology in itself, was just brilliant.”

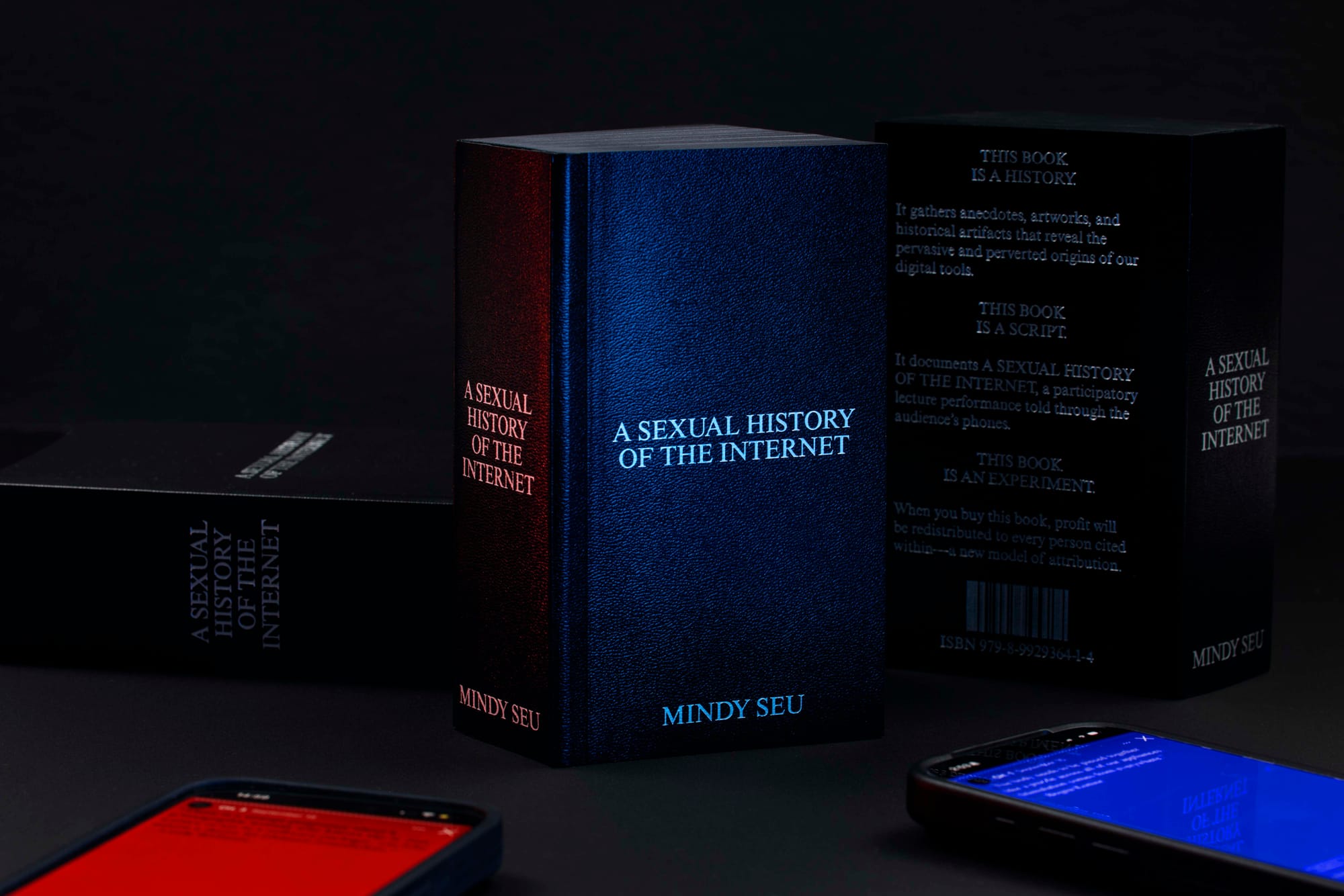

While Instagram Stories offered an accessible way to connect people through performance, it also introduced some limitations. Much of the content was ephemeral, or subject to censorship from Meta’s opaque community guidelines. The idea of printing a physical record of the performance spawned from a preservationist impulse: Books are a resilient technology. Designed by Laura Coombs, the printed edition is a palm-sized brick, bound in black leather-like vinyl, with over 700 pages of “script” printed in silver ink. At this scale, the bibliographic tome is meant to evoke the pace of the performance: one Instagram Story equals one page. However, the book expands on the digital experience with landscape images, browser windows, and widescreen videos rendered horizontally across its pages.

Published independently through Metalabel, a platform for collective releases, the book also enacts a financial experiment rooted in shared authorship. “We’re taught to valorize academic citations for good reason: Their lifeline is the peer review,” Seu observes, “but they can also be quite exclusionary.” In response, A Sexual History of the Internet introduces a “Citational Split”: 30% of profits are redistributed among those cited. Alongside formal citations are emergent forms of transfer — community citations, social citations — all of which are made equivalent in the bibliography and profit structure.

In keeping with Seu’s commitment to transparency, this test case in experimental publishing is a natural extension of the book’s core politics. “The stories in A Sexual History of the Internet are not the stories of the internet's traditional heroes,” artist and contributor Sarah Friend adds. “Instead, many of them are about the exploitations, abuses, and crimes of those heroes. This complicates a utopian understanding of how technology has been built and whose interests it's served.”

What Seu offers is a new kind of cultural infrastructure, positioning the archive itself as a kind of activism. A Sexual History of the Internet preserves informal knowledge, cleverly redistributes credits, and resists the erasure that so often accompanies digital culture. In its multi-discursive, layered ecosystem (from performance to book and back again), the project asks us to imagine what a consensual internet might look like.