The Mouse, an Unexpected and Enduring Art Muse

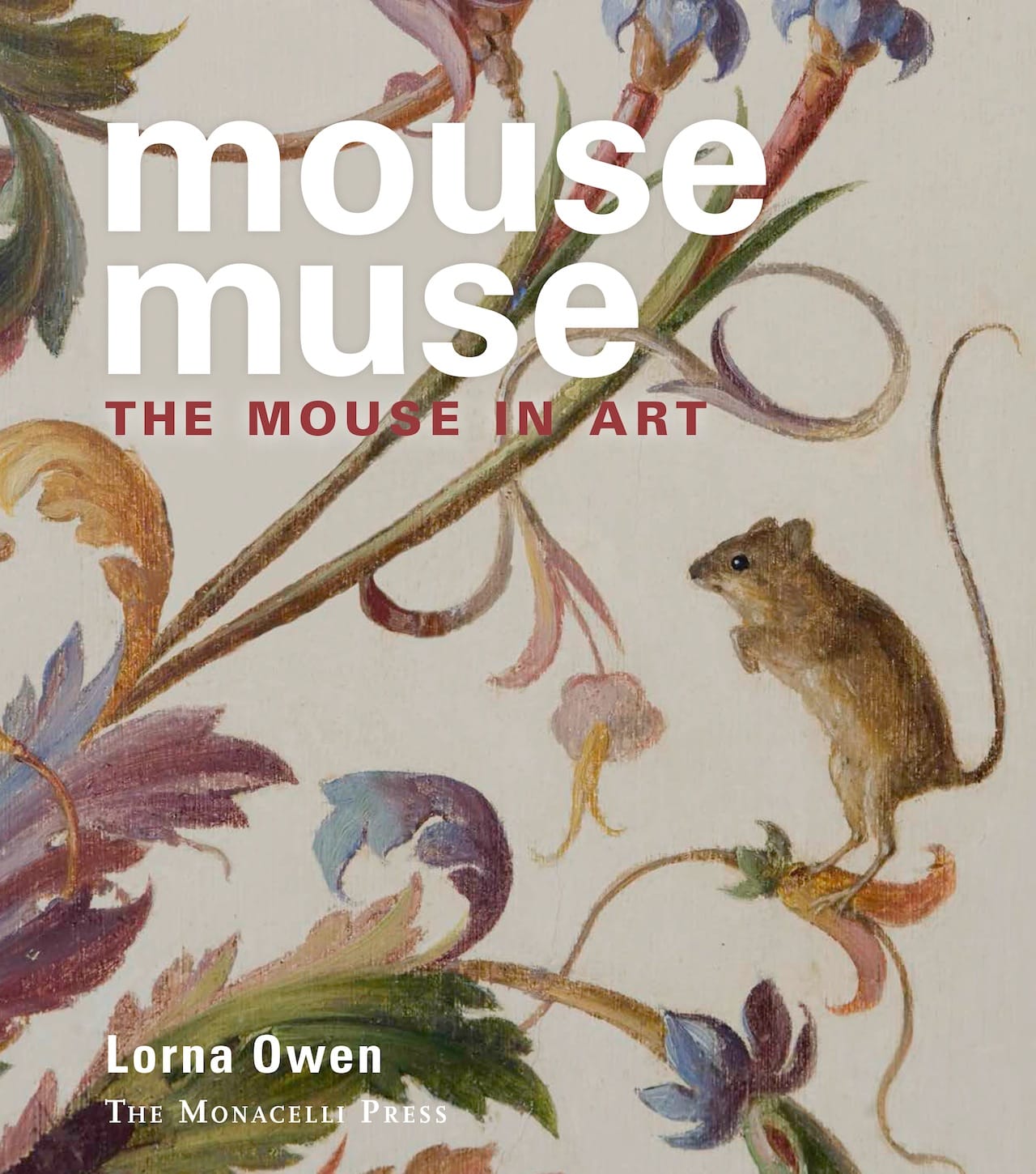

As one of the most common mammals on our planet, the diminutive mouse has been scurrying its way into art for centuries. The rodent has now finally received its own art compendium with Lorna Owen's Mouse Muse: The Mouse in Art, out next week from Monacelli Press.

As one of the most common mammals on our planet, the diminutive mouse has been scurrying its way into art for centuries. The rodent has now finally received its own art compendium with Lorna Owen’s Mouse Muse: The Mouse in Art, out next week from Monacelli Press.

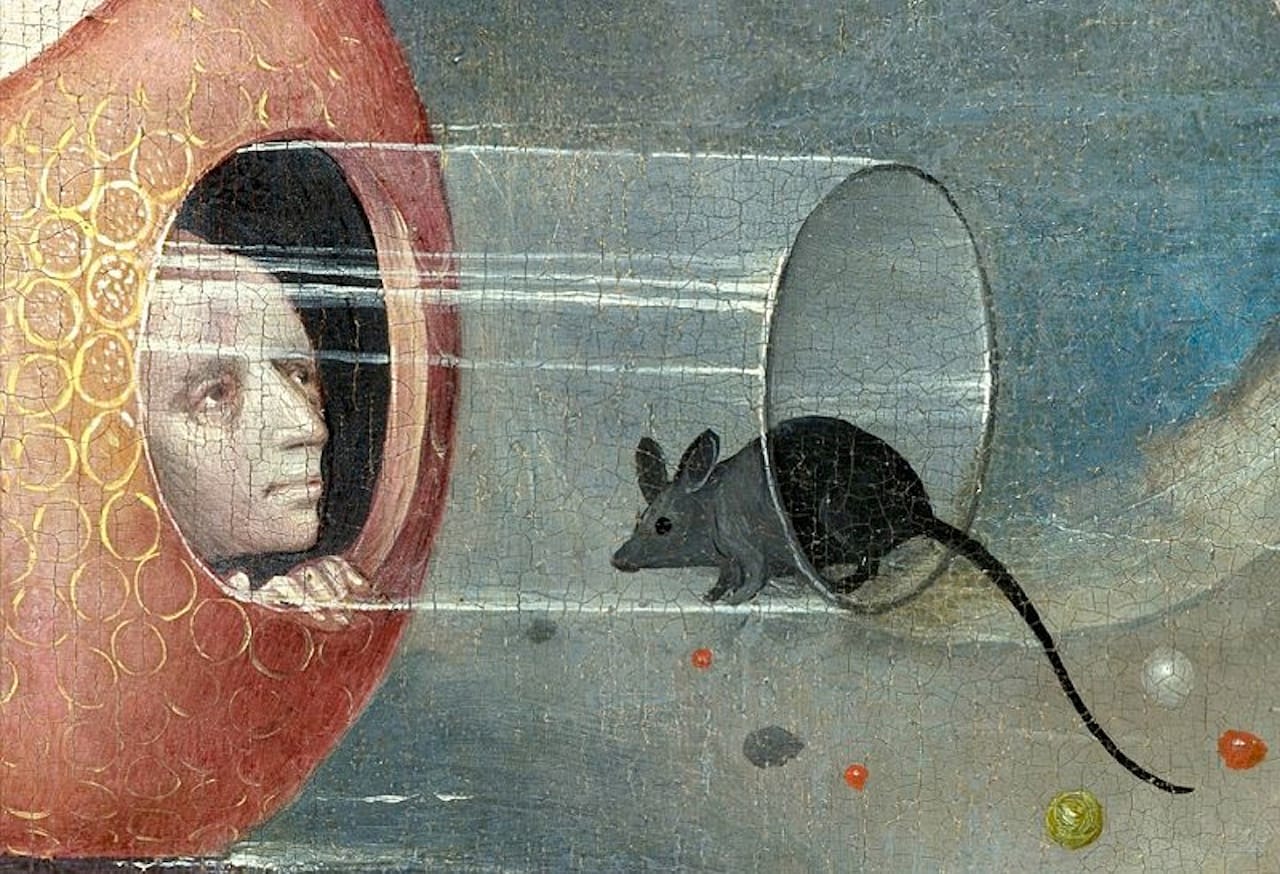

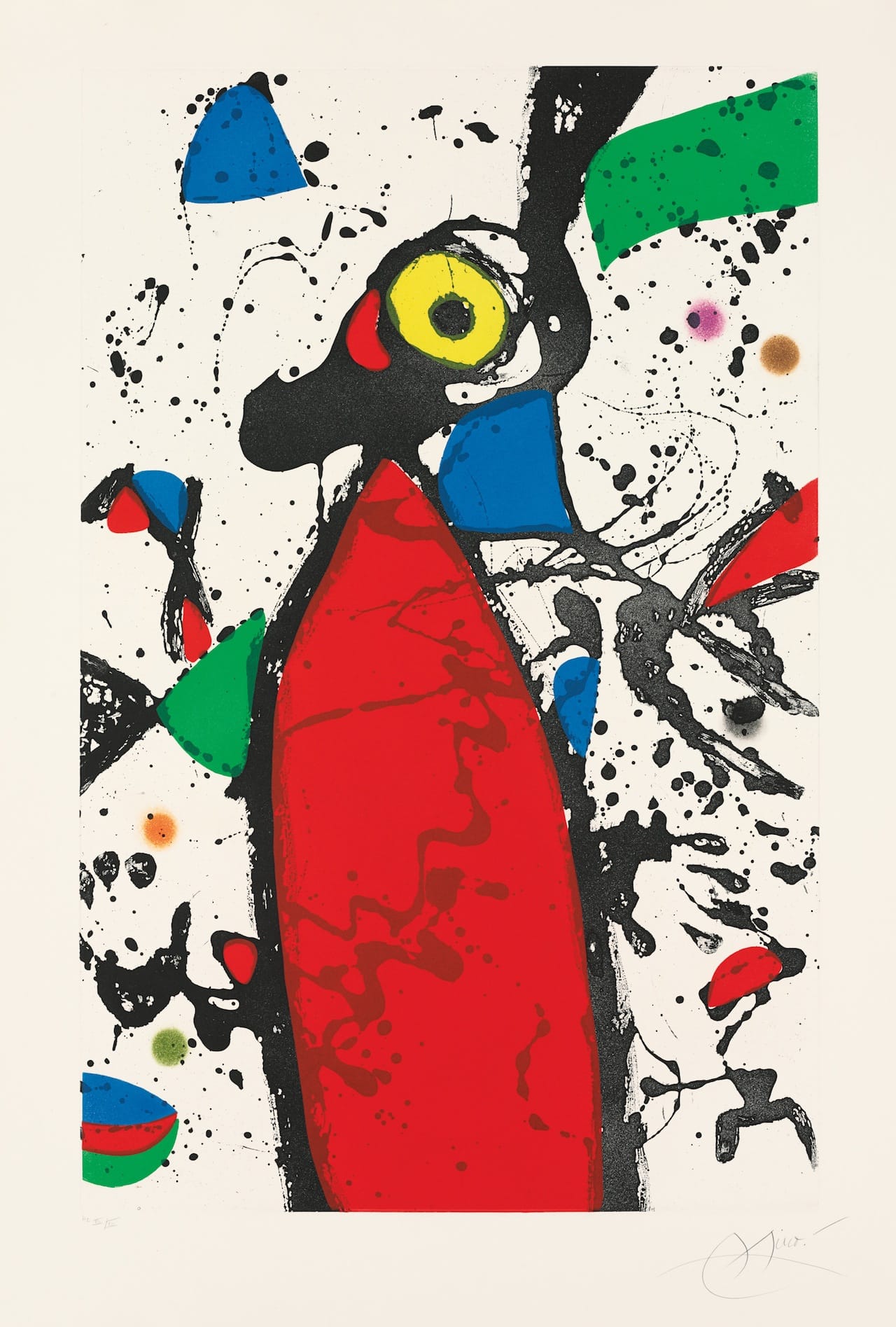

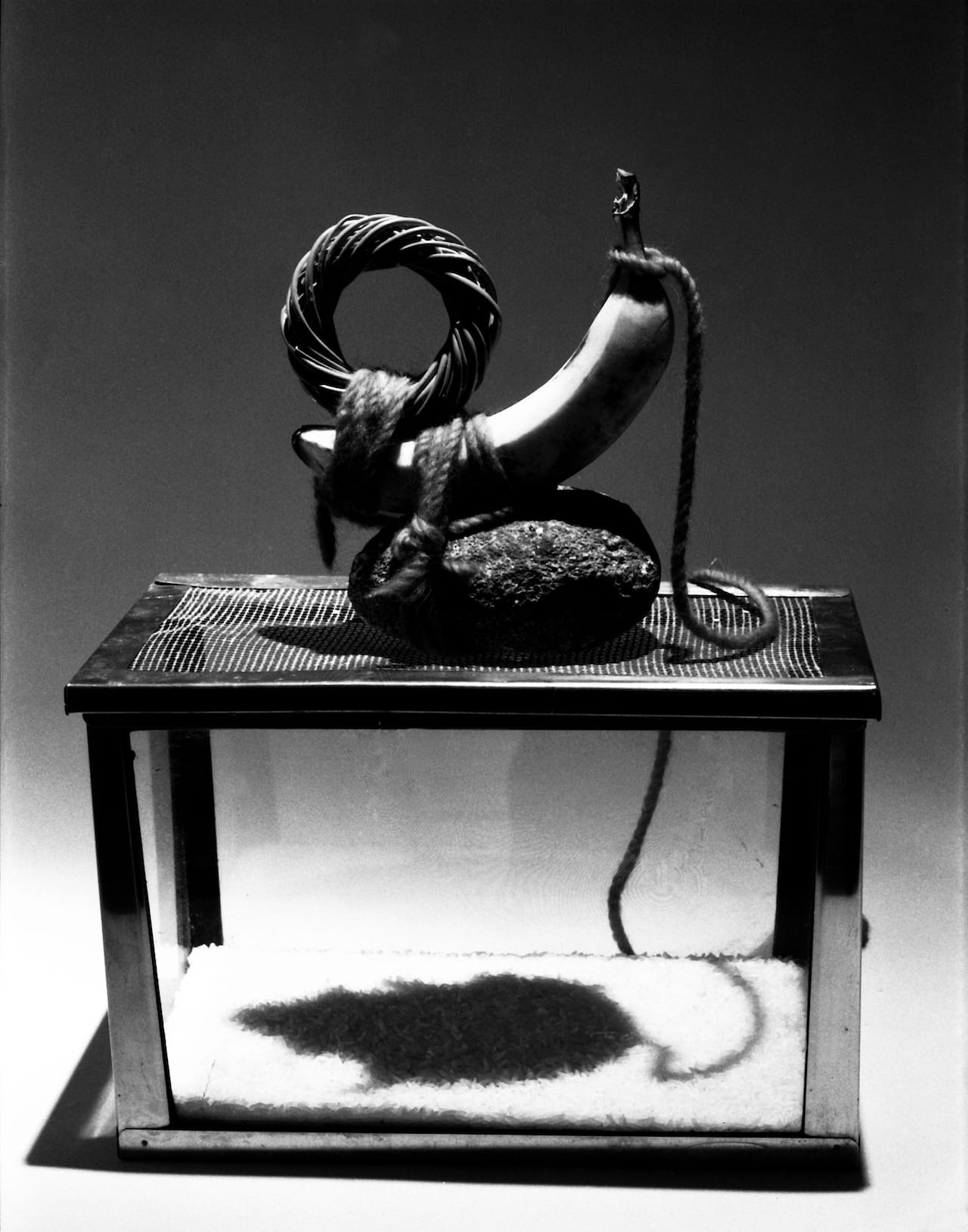

Much of the book is derived from her Mouse Interrupted blog, which seeks out the animal in all eras and forms of art, like the wide-eyed creature gazing at a human in a glass cylinder among the wild symbolism of Hieronymus Bosch’s “The Garden of Earthly Delights,” or the live creatures roaming through contemporary work by Carsten Höller and Liselot Van der Heijden. Owen explained her interest in the art mouse to Hyperallergic:

The mouse is a remarkable mammal. In broad strokes, it has an acute sense of smell that actually surpasses that of cats and dogs; it is an excellent swimmer; and it’s been found to sing, ultrasonically, with actual repertoires of specific phrases. But what is provocative is that here we have a mouse, which many consider to be an insignificant creature; yet its well-known traits have sparked in art some of the most powerful expressions of who we are as humans — qualities that are often diametrically opposed: good and evil, industrious and shiftless, cowardly and courageous.

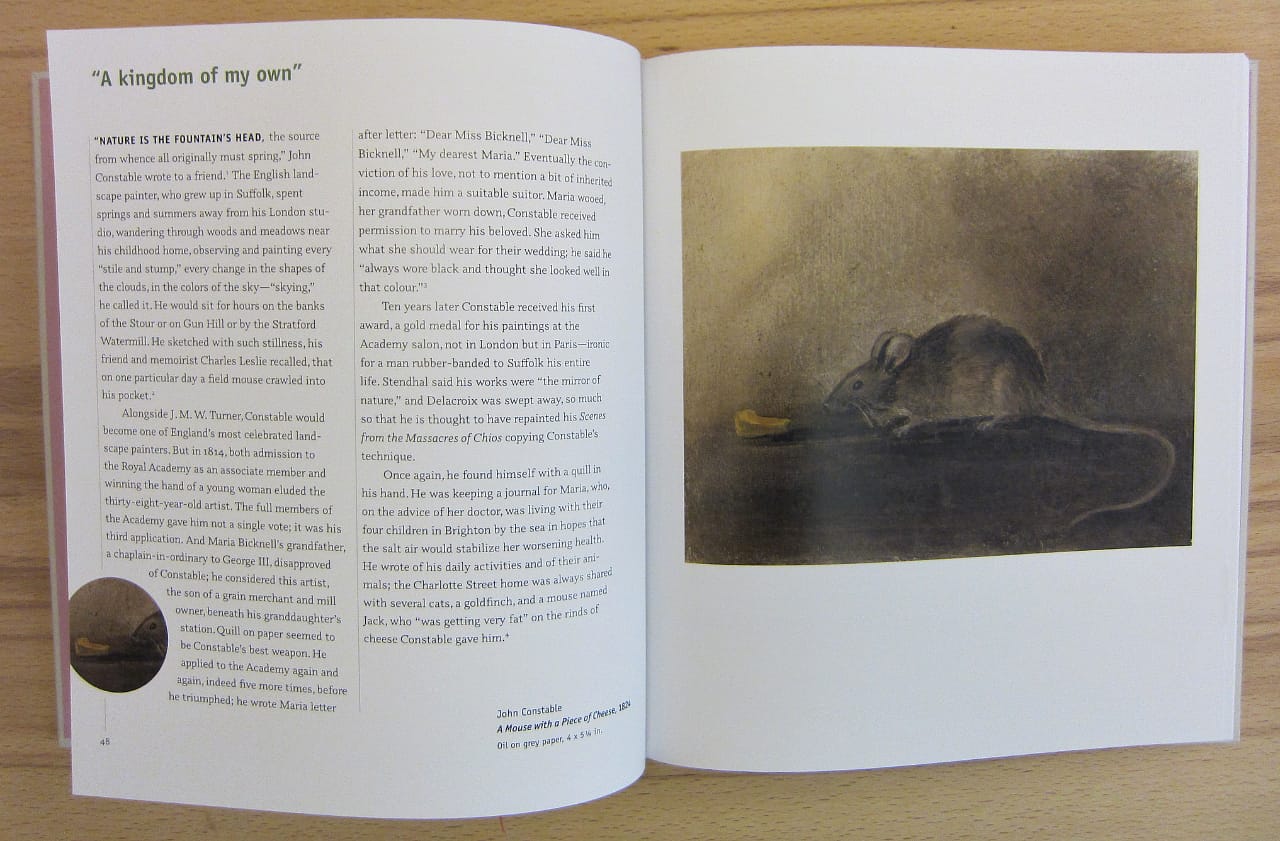

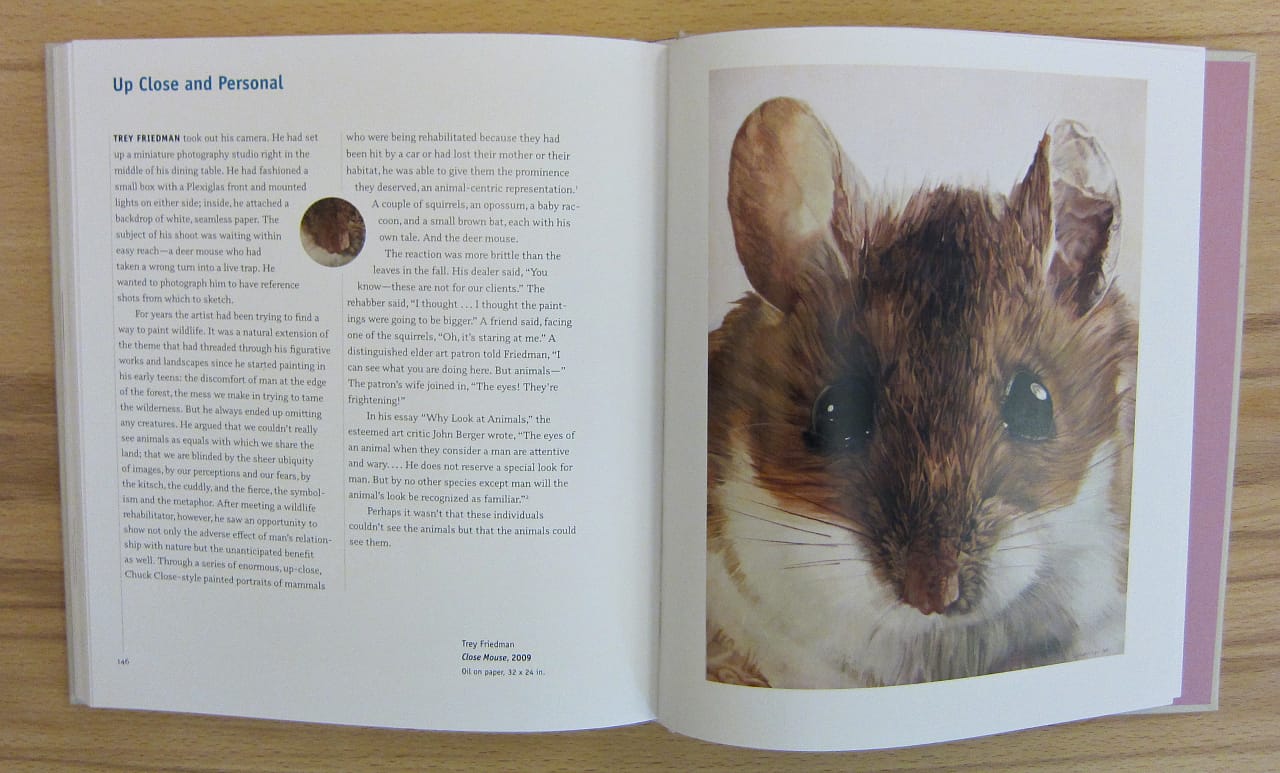

Mouse Muse includes over 80 works in a compact hardback, with each example joined by a short essay exploring its history and reason for having a mouse, the full print of the piece paired with a detail of the mouse embedded in the text. And the reasons for including mice have changed over time, from empathetic bronzes in ancient Rome found in nearly every household, to an unwanted symbol of mortality lurking in still-lifes. Owen tracked down the vermin by examining works by artists known for their love of nature like Frans Snyders and Franz Marc, and even delved into journals and letters by artists, finding some surprises along the way such as that “Kandinsky was inspired by the placental tissue of a mouse for his biomorphic abstract painting ‘Capricious Forms.’”

Plenty of these discoveries are pocketed in Mouse Muse, some that show the woe that is the role of the animal model. While John Constable, who painted an 1824 portrait of “A Mouse with a Piece of Cheese,” delighted in caring for his mouse named Jack, for Sir John Everett Millais it was easier to have a more inert subject. In his 1851 “Mariana” a mouse quietly moves in the daylight shining through the stained glass by his Pre-Raphaelite lady. The little animal had been found by Millais in his studio right when he was wanting to include one in the painting, and as it darted behind a portfolio he kicked the case over and killed it, as he put it, “in the best possible position for drawing it.” Yet whether reviled infestation or resilient beast, the mouse definitely seems to have in its quiet way burrowed into the history of art.

Mouse Muse: The Mouse in Art by Lorna Owen is available November 18 from the Monacelli Press.