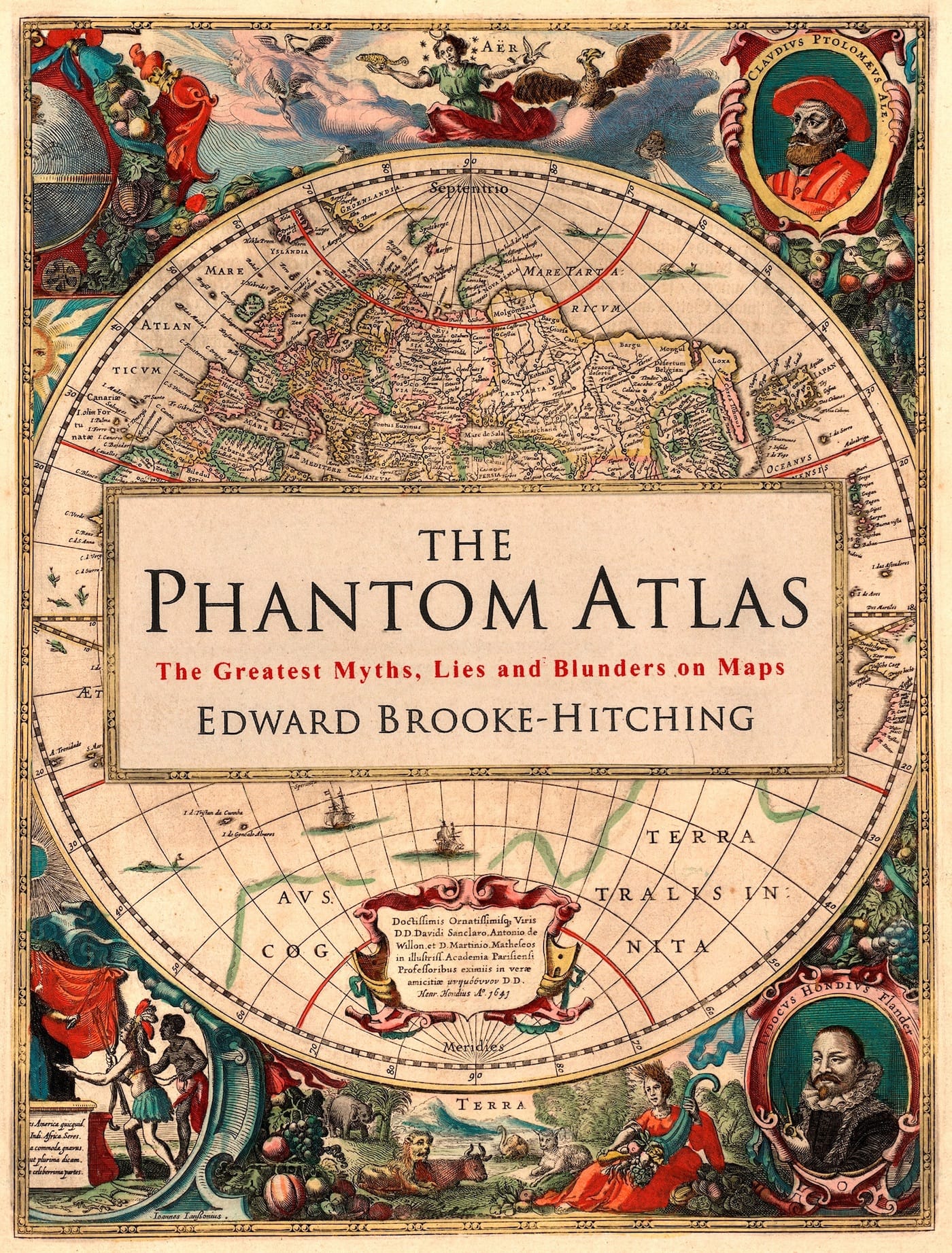

An Atlas for the Mythical Places that Have Populated Our Maps

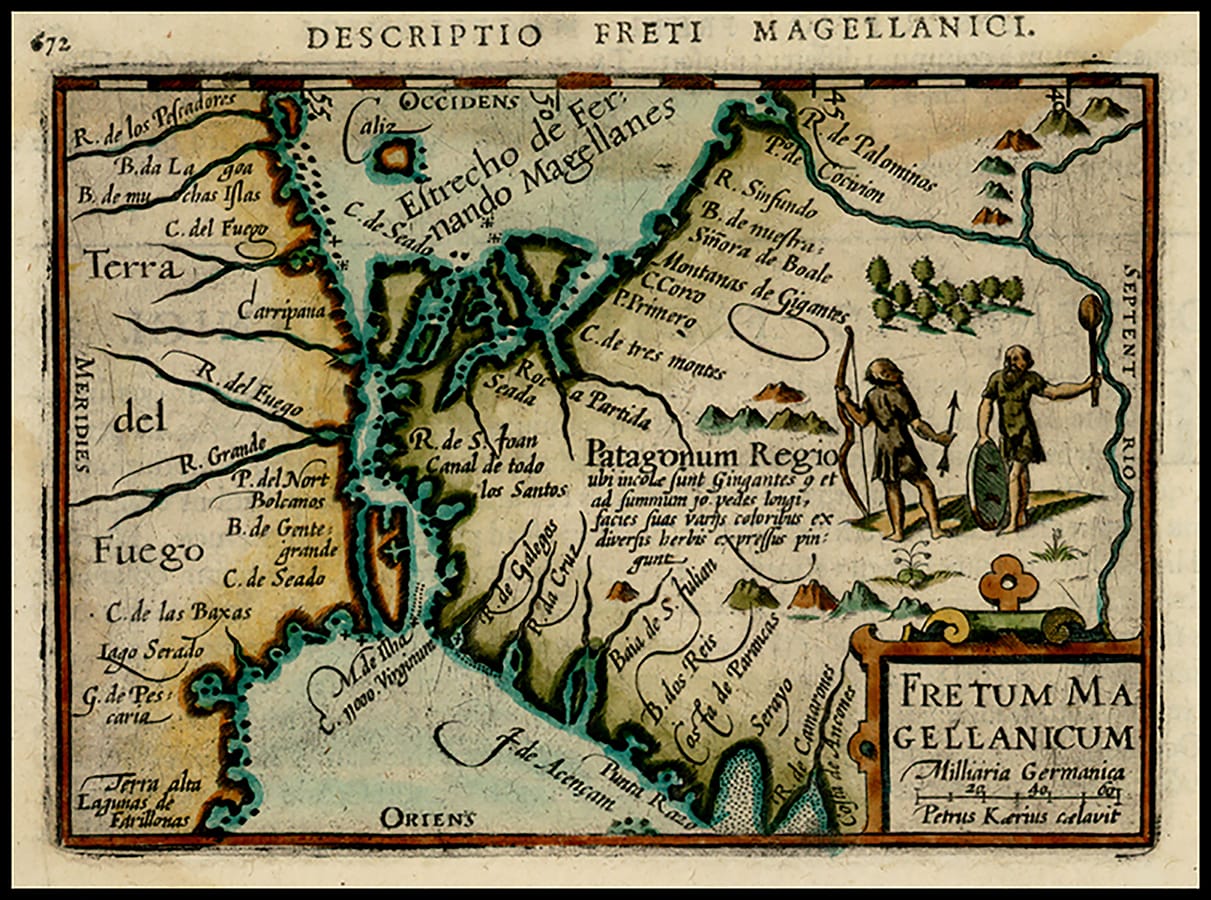

The Phantom Atlas chronicles centuries of fictional locations that were included on maps of the world.

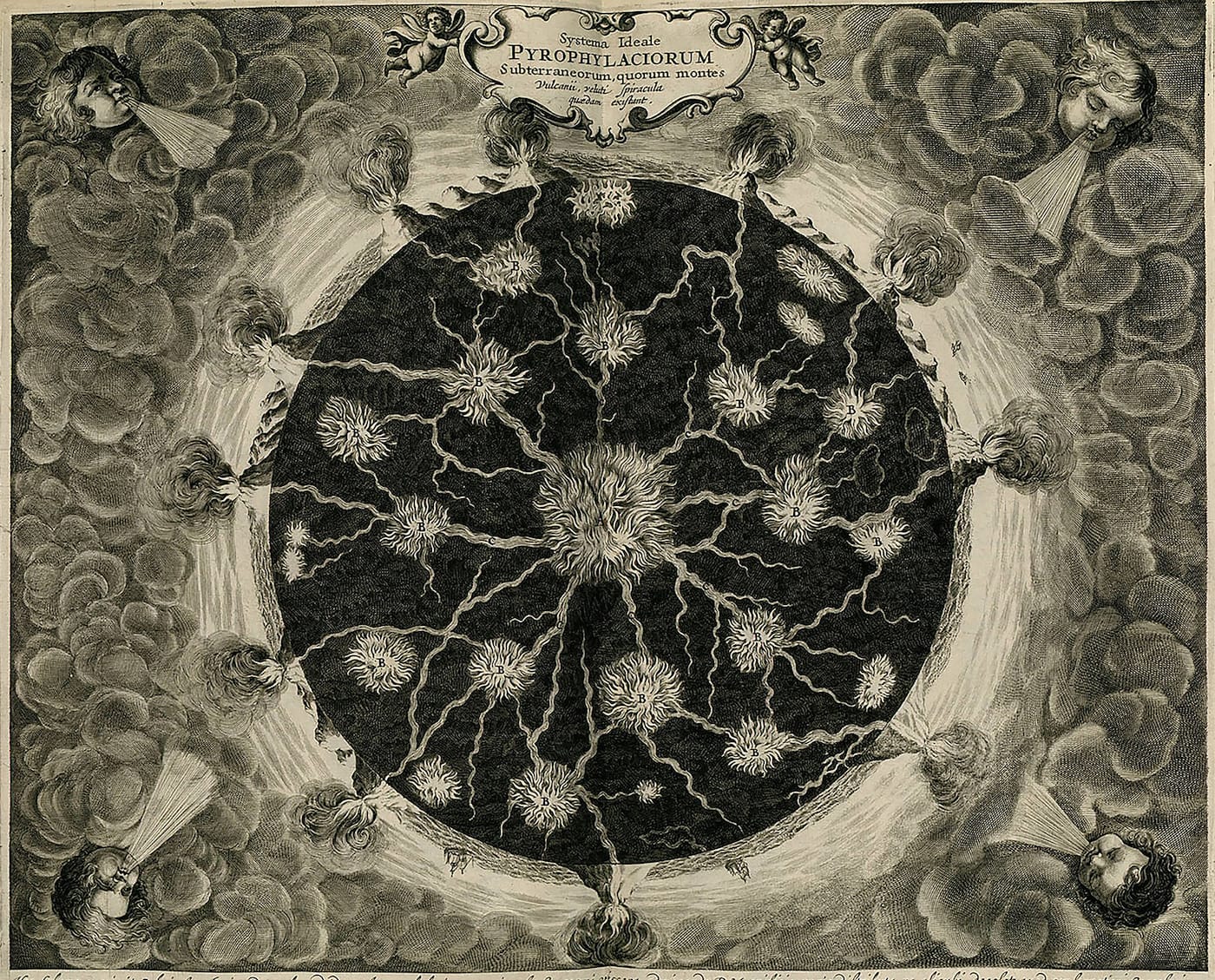

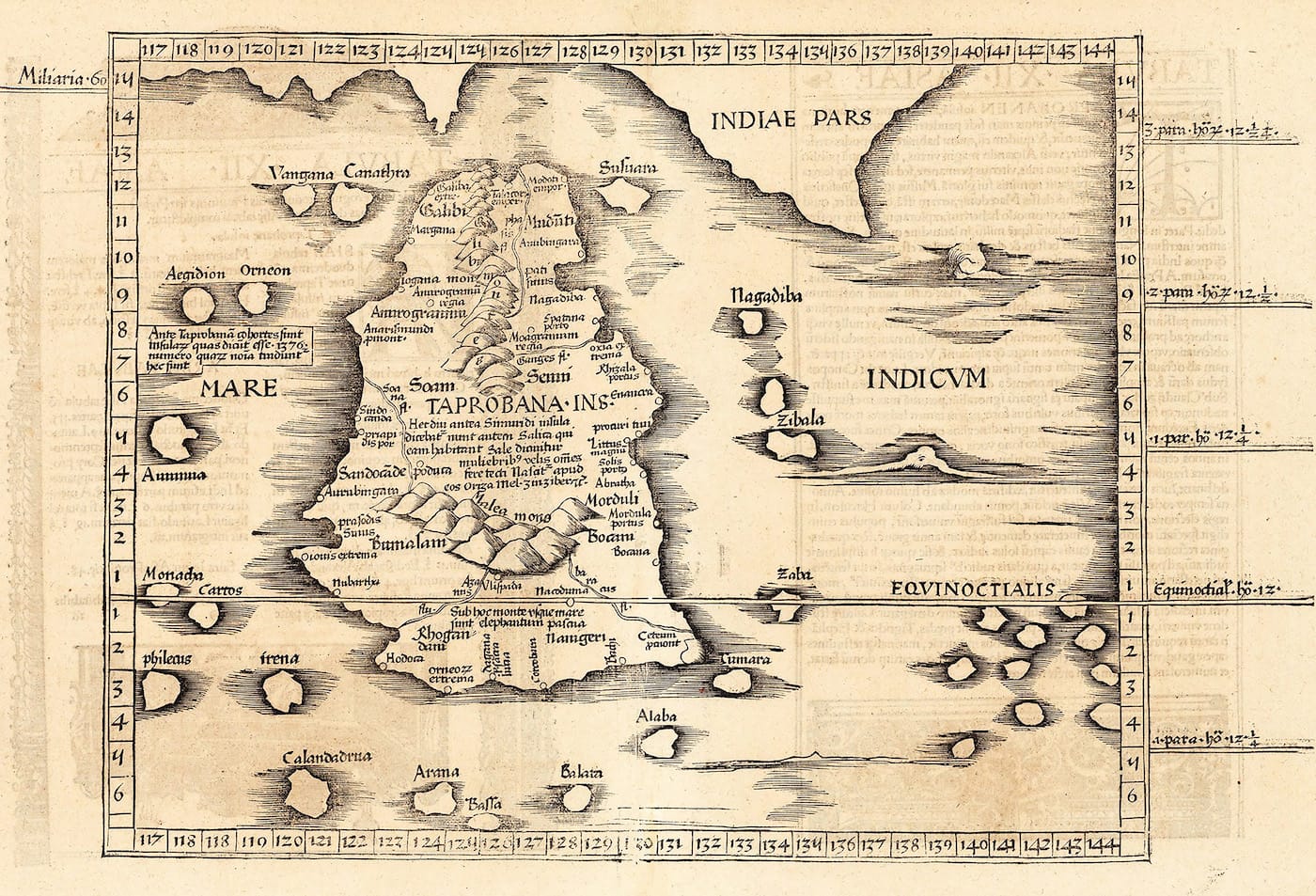

Atlantis may be the most famous of mythical destinations, but the history of cartography is strewn with non-existent places. California appeared as an island on numerous 17th-century maps, and a 16th-century “Map of the Arctic” by Gerardus Mercator included a colossal magnetic mountain at the North Pole. The Phantom Atlas: The Greatest Myths, Lies and Blunders on Maps by Edward Brooke-Hitching, out now from Simon & Schuster UK, examines the strange endurance of legendary places on our maps.

“This is an atlas of the world — not as it ever existed, but as it was thought to be,” Brooke-Hitching writes in an introduction. “The countries, islands, cities, mountains, rivers, continents, and races collected in this book are all entirely fictitious; and yet each was for a time — sometimes for centuries — real. How? Because they existed on maps.”

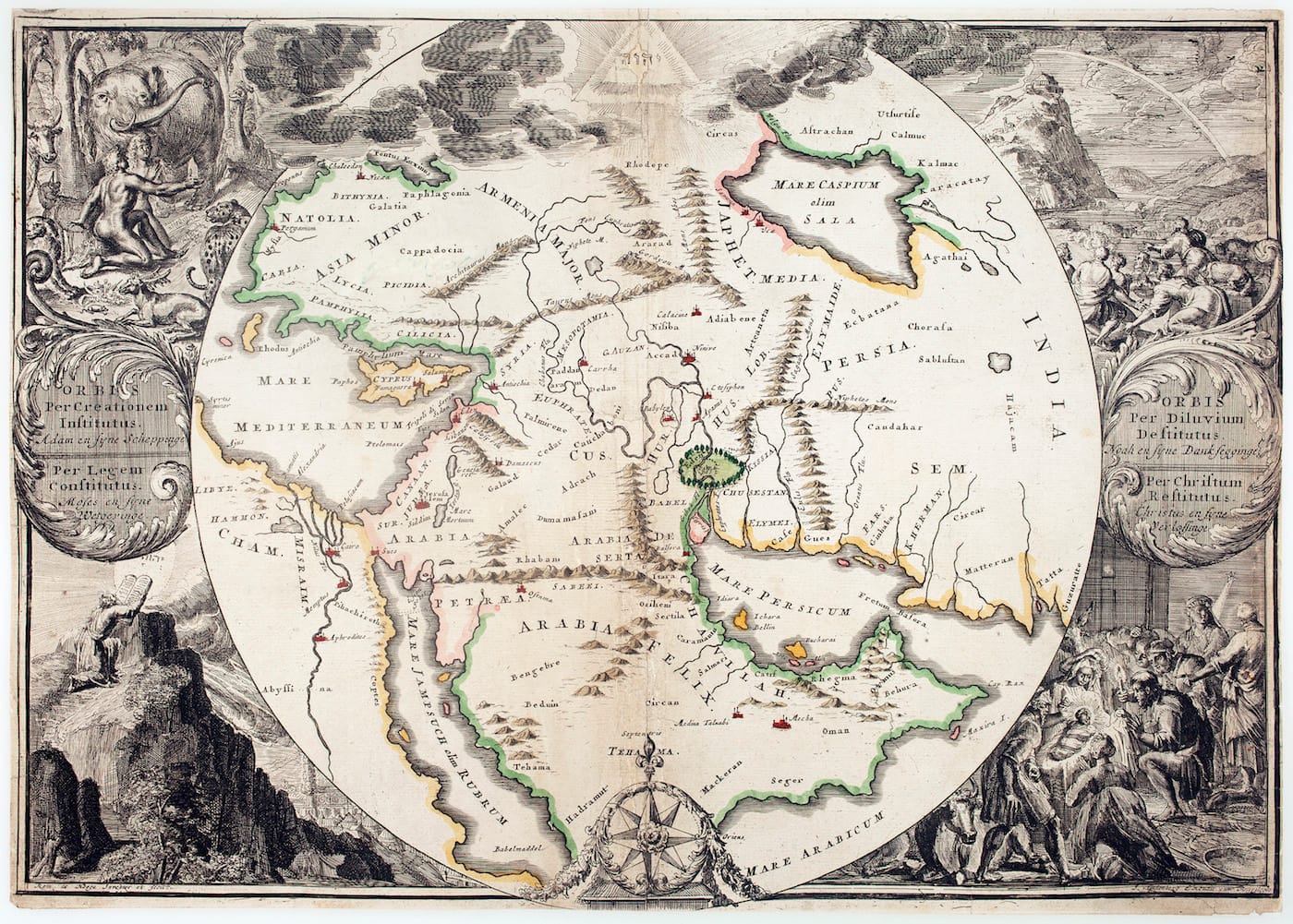

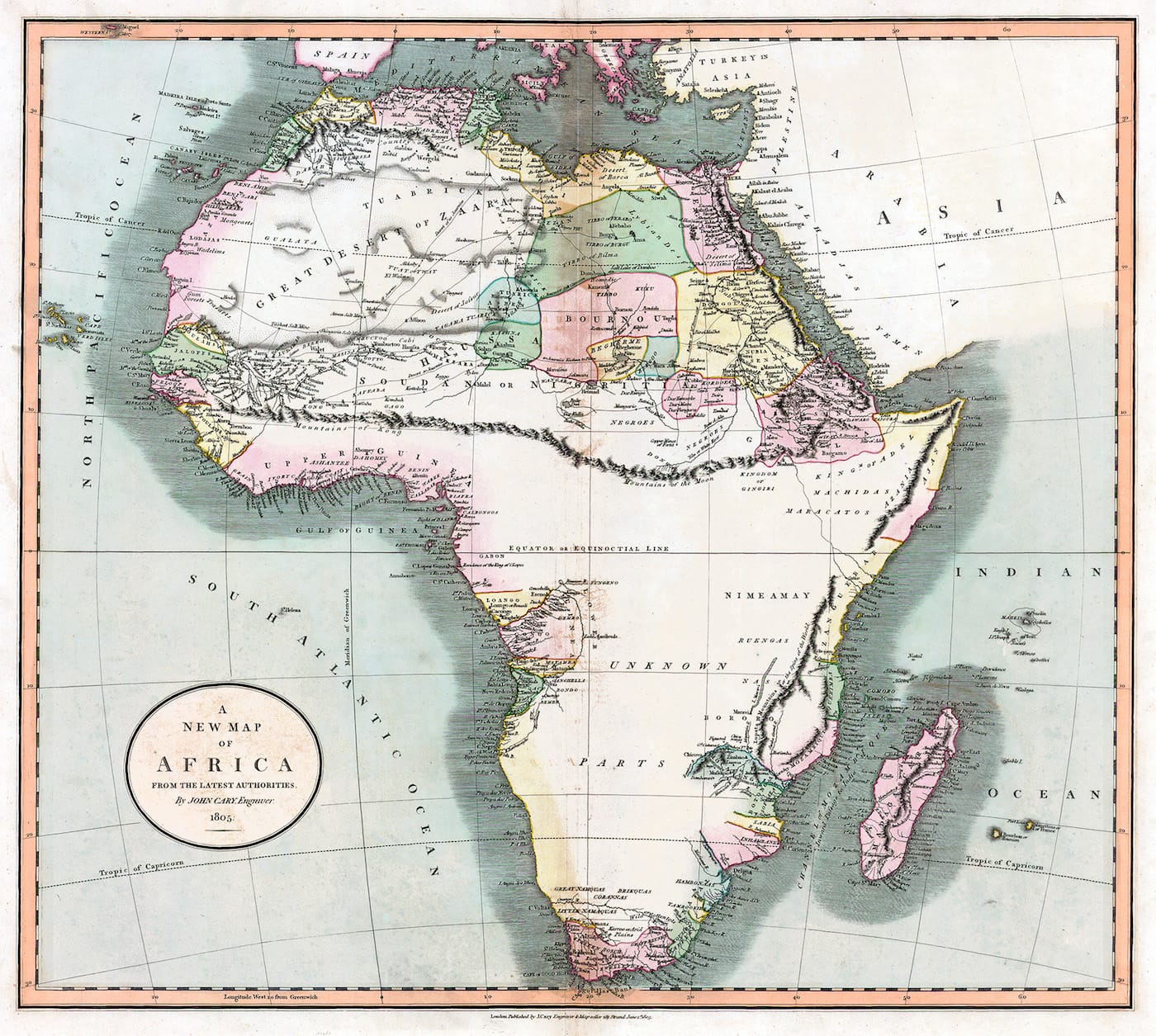

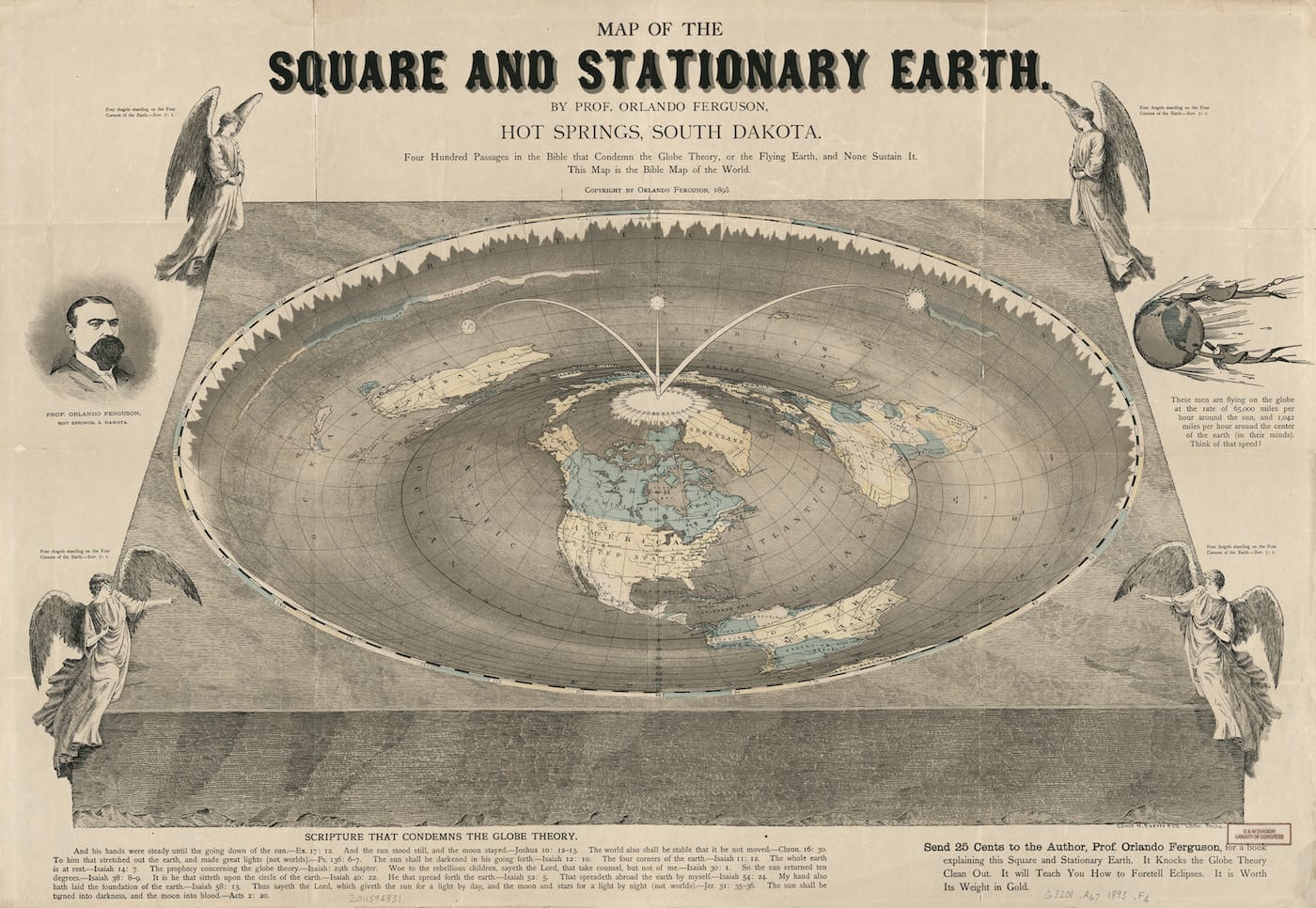

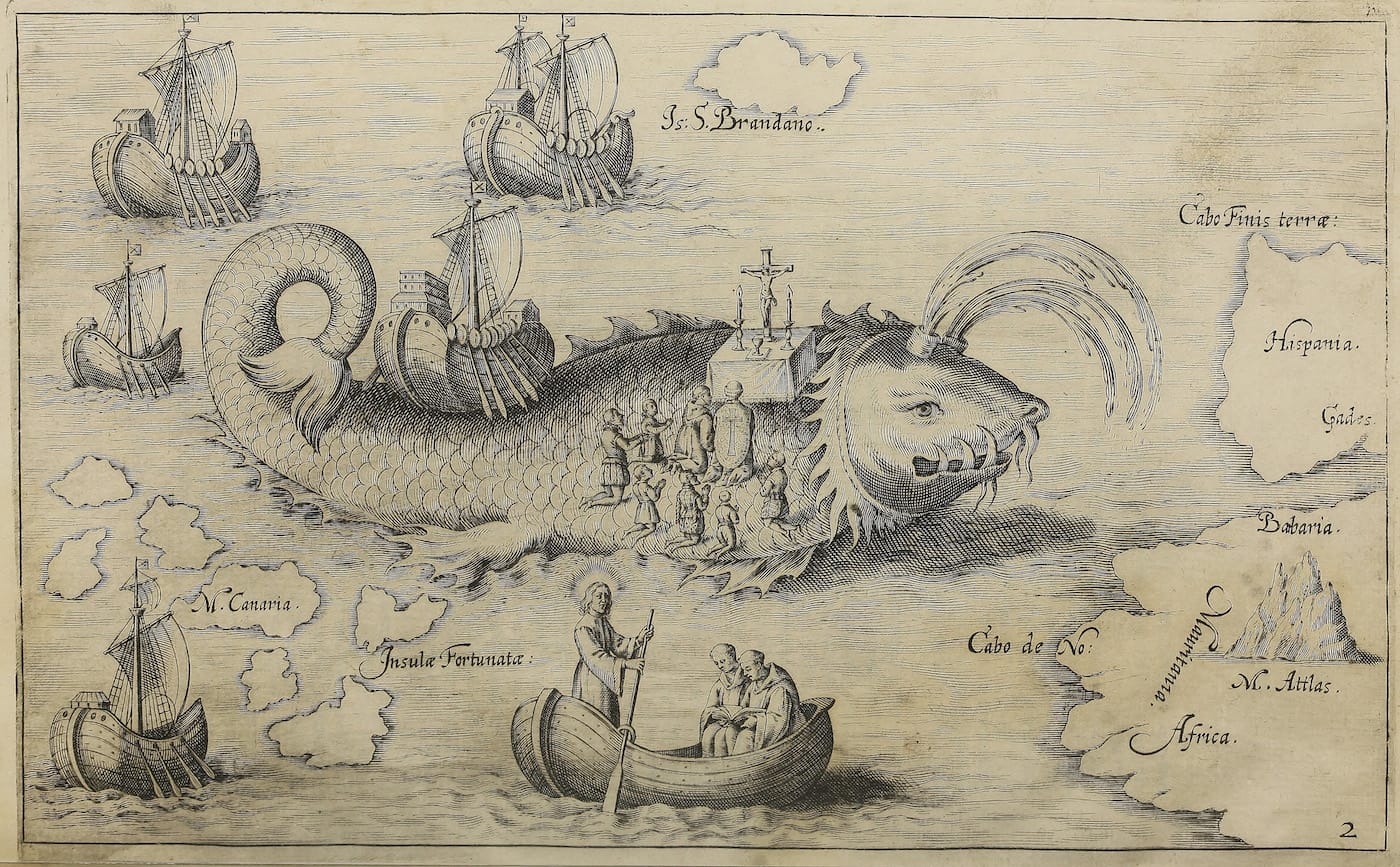

Mythical islands were often copied by mapmakers, who, for instance, could not easily voyage out to the Southern Hemisphere to see if it did indeed have the giant Terra Australis continent. The Phantom Atlas includes Hy Brasil, recently the subject of a Boston Public Library exhibition, which stayed on maps for five centuries, and had tales of a sorcerer who lived with huge black rabbits and, later, UFOs. Although Brooke-Hitching features extremes of credulity, like a 40-foot “sea worm” that roamed the shores of Norway on a 16th-century map by Olaus Magnus, he also cites more recent mistakes. Sandy Island was recorded in the eastern Coral Sea by a whaling ship in 1876, and it wasn’t until November 2012 that it was deemed fictional. And in the 19th century, there were still those who believed in a flat Earth, such as Professor Orlando Ferguson of Hot Springs, South Dakota, who in 1893 illustrated a map arguing for this planar view of the planet, which he based on biblical texts.

What makes Brooke-Hitching’s book more than just a collection of oddities is the emphasis on why these errors happen, and how relying on religion at the exclusion of science, or valuing outsider reports ahead of indigenous knowledge, detrimentally impacted centuries of exploring. Some figures in The Phantom Atlas, though, were just liars. In the 19th century, the Scottish conman Gregor MacGregor swindled hundreds of British and French investors with his reports of the imaginary “Cazique.” Some people even journeyed out to this Central American locale, only to find a wild jungle instead of a town, and death instead of a new life.

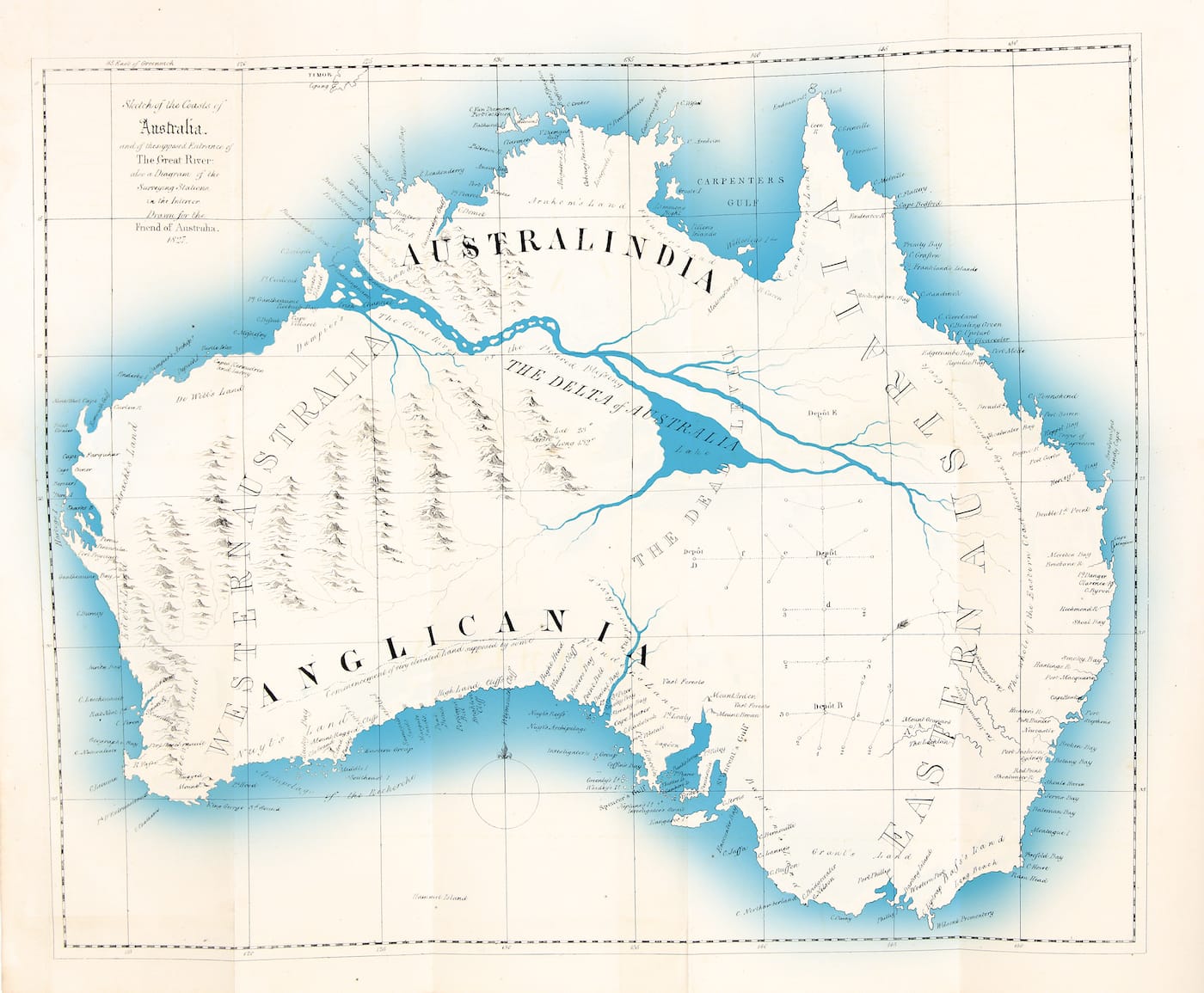

Below are a few selections from The Phantom Atlas, from erroneous inland seas of Australia, to the Garden of Eden plotted on an 18th-century map.

The Phantom Atlas: The Greatest Myths, Lies and Blunders on Maps by Edward Brooke-Hitching is out now from Simon & Schuster UK.