The Power of Making Art From a Prison Cell

A show demonstrates how deeply meaningful creative processes can be for incarcerated people and the larger public.

SANTA FE — Prison constricts human realities. One way to escape is through acts of imagination, as seen in an intricately folded paper eagle poised for takeoff in Between the Lines: Prison Art & Advocacy at the Museum of International Folk Art, Santa Fe. Made by Djan Shun Lin, who was imprisoned after the ship he and hundreds of other Chinese asylum-seekers were aboard ran aground in New York in 1993, “Eagle” (1993–96) symbolizes a yearning for freedom from both a repressive homeland and the prison cell. Through this and many other projects, as well as direct testimony from artists themselves, viewers come to understand how deeply meaningful creative processes can be for individual and social understanding. Such reckonings, combined with awareness of the brutal and lengthy sentences many individuals are forced to endure, have the power to catalyze profound compassion.

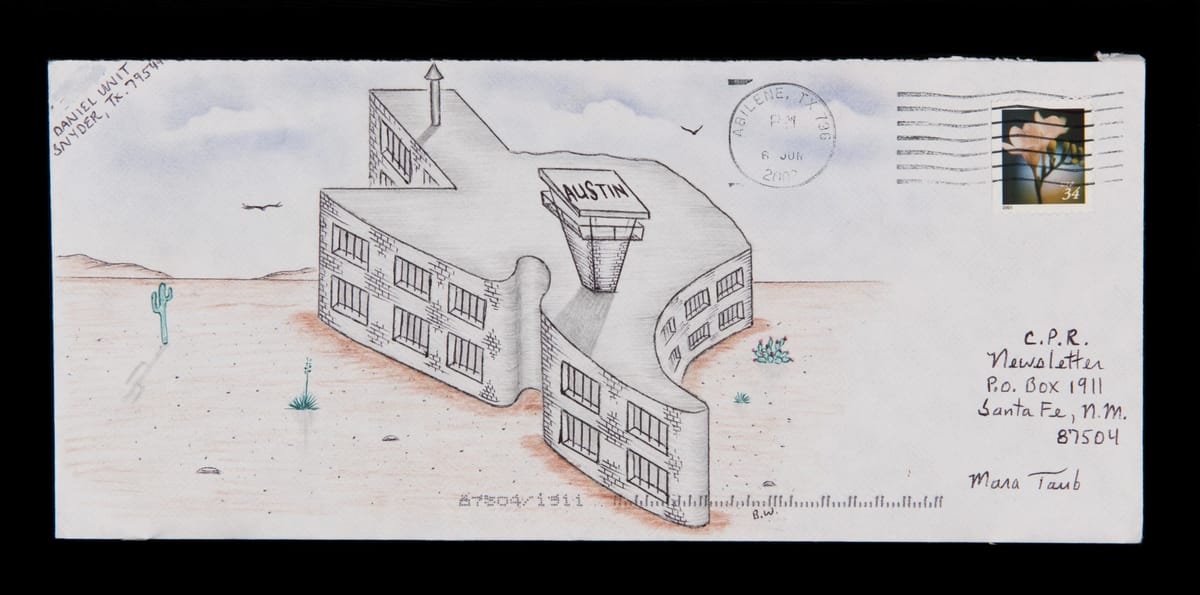

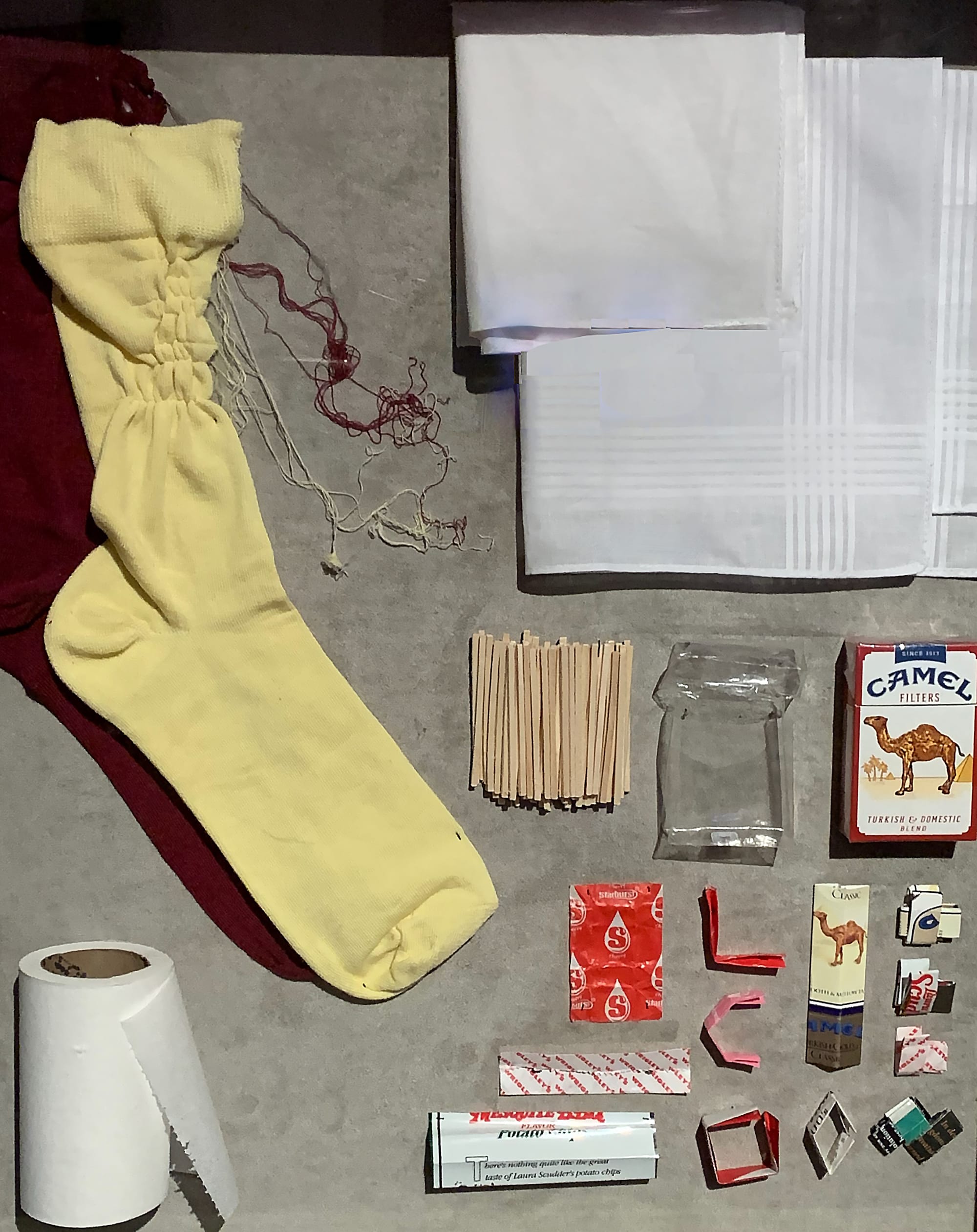

Between the Lines is installed in an open-plan space with a subtle color palette, notably unlike the cramped, divided, and stark conditions of penitentiaries, making the work more accessible. It also humanizes, rather than fetishizes, both art and artist. The art encompasses a wide range, including sculpture (animals are prevalent), jewelry, decorated clothing, murals, and paño arte (ink drawings on fabric). Unsurprisingly, given the resource-poor context in which they were made, these works are constructed from an inventive array of repurposed materials: pillowcases, sock threads, handkerchiefs, candy wrappers, cigarette packages, and matchsticks. This resourcefulness sometimes approaches genius: In a video demonstrating prison tattooing, formerly incarcerated artist Candice Martinez disassembles a hair dryer and repurposes cigarette lighters and ballpoint pens to create a tattoo gun, showing off the word “Courage” lettered on her foot.

In rare cases, incarcerated creators become well-known. The exhibition includes a large-scale paper bag drawing by celebrated “outsider artist” Martin Ramirez and a striking small-scale sculpture of a courtroom scene by noted Tesuque Pueblo artist Manuel Vigil. Others, though not widely recognized, build familial and/or local recognition for their work — arguably a key component of social restoration for those “serving time.” As one practical example, in an interview part of one of the exhibition’s videos, incarcerated artist Jerry Tapia celebrates his art’s monetary earnings, ensuring that he doesn't have to “ask any of my family.”

As a whole, Between the Lines is ambitious in its global reach and historical scope. It includes a small section dedicated to ethnic Japanese people the United States interned during World War II, and an early 2000s-era woodcarving from Palau signed by “Bayo R.” proves how normalized and far-flung carceral regimes have become. Though representation is concentrated on more contemporary artists in Southwestern institutions, the show highlights broader concerns of harsh conditions, alienation, and yearnings for better human outcomes.

Larger issues around incarceration, such as the racism of the United States justice system, are not explicitly confronted in the exhibition. Nor are more pointed questions, such as “What is prison for?” — just punishment? Rehabilitation? More secure societies? Though there’s no direct address to ideas of prison reform, much less abolition, there is implied consideration of how greater official valuing of prison art could help better restore justice than the current prevailing constrictions of incarceration.

Since 2012, Brazil’s “Remission for Reading” program has reduced individuals' sentences when they read books and write reports, leading to dramatic reductions in recidivism. Between the Lines suggests, by showing incarcerated individuals developing skills and forging communities, that something similar might be successfully applied to art-making. Instead of endlessly being held to task for past actions, perhaps these artists could be supported in creating, building, and restoring a future through more positive actions in the present.

Between the Lines: Prison Art & Advocacy continues at the Museum of International Folk Art (On Museum Hill, 706 Camino Lejo, Santa Fe, New Mexico) through September 2. The exhibition was curated by the museum.