Paging Through Chris Marker’s Studio, a Spatial Representation of His Mind

A new book takes readers into the workspace of the venerated filmmaker.

Five years after his death at the age of 91, Chris Marker’s presence is still felt. The puckish filmmaker — although he was often in the public eye, he also went out of his way to avoid celebrity and publicity — made Letter to Siberia (1958) and Sans Soleil (1983), the latter a landmark in the tradition of essay filmmaking, one that is booming right now in contemporary cinema with films like What Now? Remind Me (2013), Counting (2015), and HyperNormalization (2016). One wonders what the maker of dystopian and cyber-paranoiac science-fiction films like La Jetée (1962) and Level Five (1997) would’ve thought about NSA surveillance, the continuing imbroglio between the Trump administration and Russia, or even Black Mirror. What kind of personal, philosophical, unclassifiable films would he have made about the technocratic nightmare we now live in?

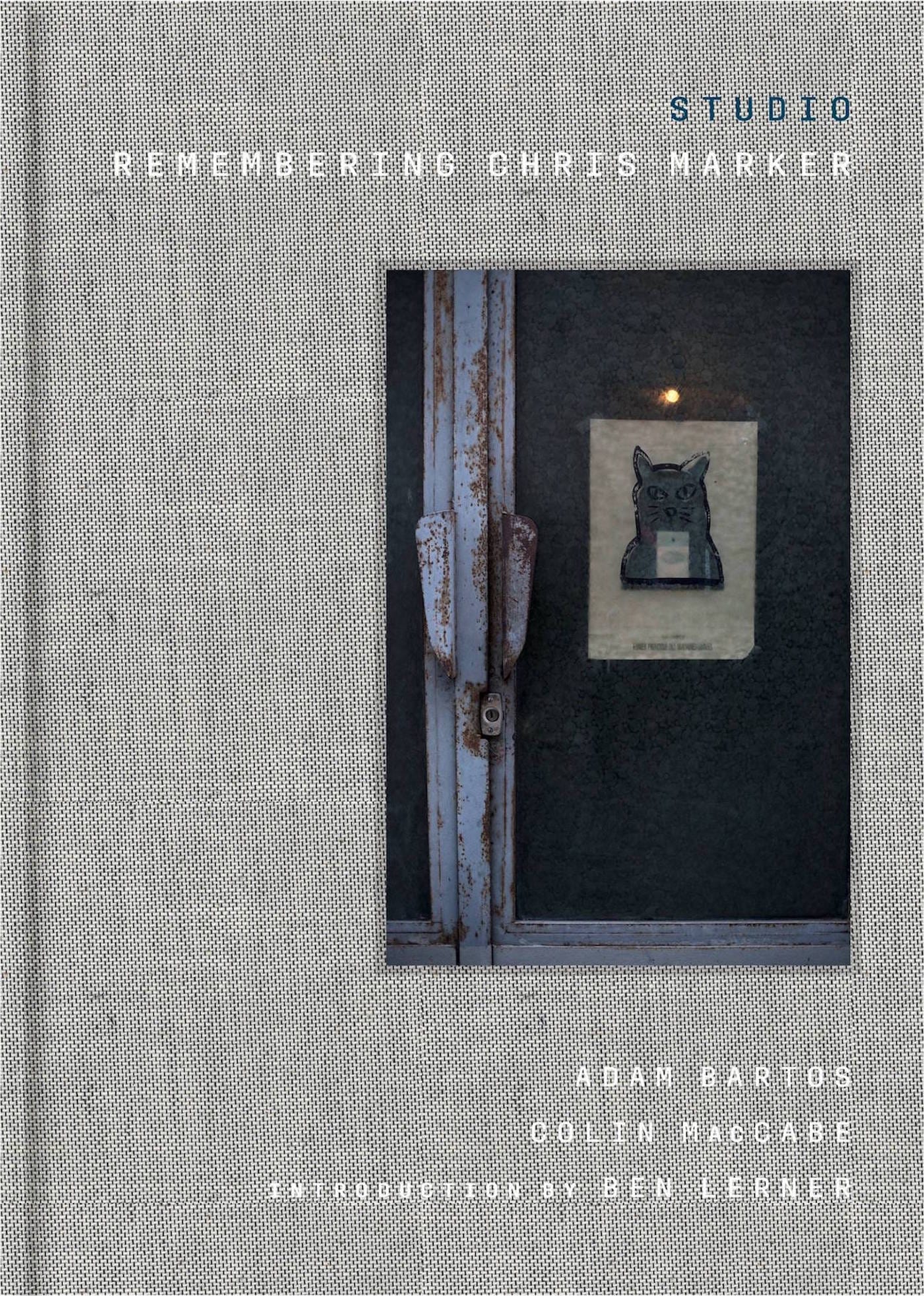

Marker’s presence also lingers in a more tangible way: his untouched Parisian studio. Studio: Remembering Chris Marker, published in May by OR Books, remembers an artist known for works about memory by concentrating on the space in which he worked. The book — designed by Adam Bartos, Hee Jin Kang, and Ben Tousle — is a slender, gray, 50-odd-page hardcover that’s inconspicuous and could easily blend in with other books on a shelf, just like Marker both appeared and disappeared in public. Studio is divided into three parts: an introduction by Ben Lerner, a personal essay by Colin MacCabe, and photos by Bartos. So the book consists of four authors, including the shadowy trace of Marker.

Lerner’s five-page introduction, which is a hint effusive, offers a lucid background on MacCabe, Bartos, and Marker. Moreover, Lerner provides a way of thinking about the book and the photographs, particularly by relating Studio to Bartos’s previous projects — International Territory (1994), Boulevard (2005), Kosmos (2001), and more — and highlighting the photographer’s fascination with what Lerner calls “old futurisms,” detritus, obsolete technologies, and the boredom and memories connected to these expired objects. In effect, then, Bartos is the ideal photographer for the tech-savvy Marker. When looking at Bartos’s images and characterizing the spaces in them, Lerner says, “Marker is everywhere and nowhere in the photographs of his studio, which is both remarkably cluttered and remarkably clean.” The filmmaker is part of the space without physically being there. Marker marks his territory.

The second section is the longest part of the book. In it, MacCabe describes his relationship with Marker in his final years. Illustrating this passage are MacCabe’s snapshots that trace the route to Marker’s studio. His essay begins, appropriately, with him handing Marker an object: a VHS of The Magic Face (1951), an obscure Frank Tuttle film that Marker hadn’t seen in 50 years. Filtered through MacCabe’s experiences and recollections, one hears about Marker’s final projects: Owls at Noon Prelude: The Hallow Man (2005) and PASSENGERS (2008–10), among others. This middle section of Studio sheds light on Marker the artist as well as Marker the man. It humanizes the (in)famous recluse who opted to speak indirectly with alter egos both in and outside of his films, like Guillaume the orange cat or owls. As MacCabe portrays him, Marker was still a very creative and very energetic artist in his 80s and 90s, tirelessly working in his twilight years.

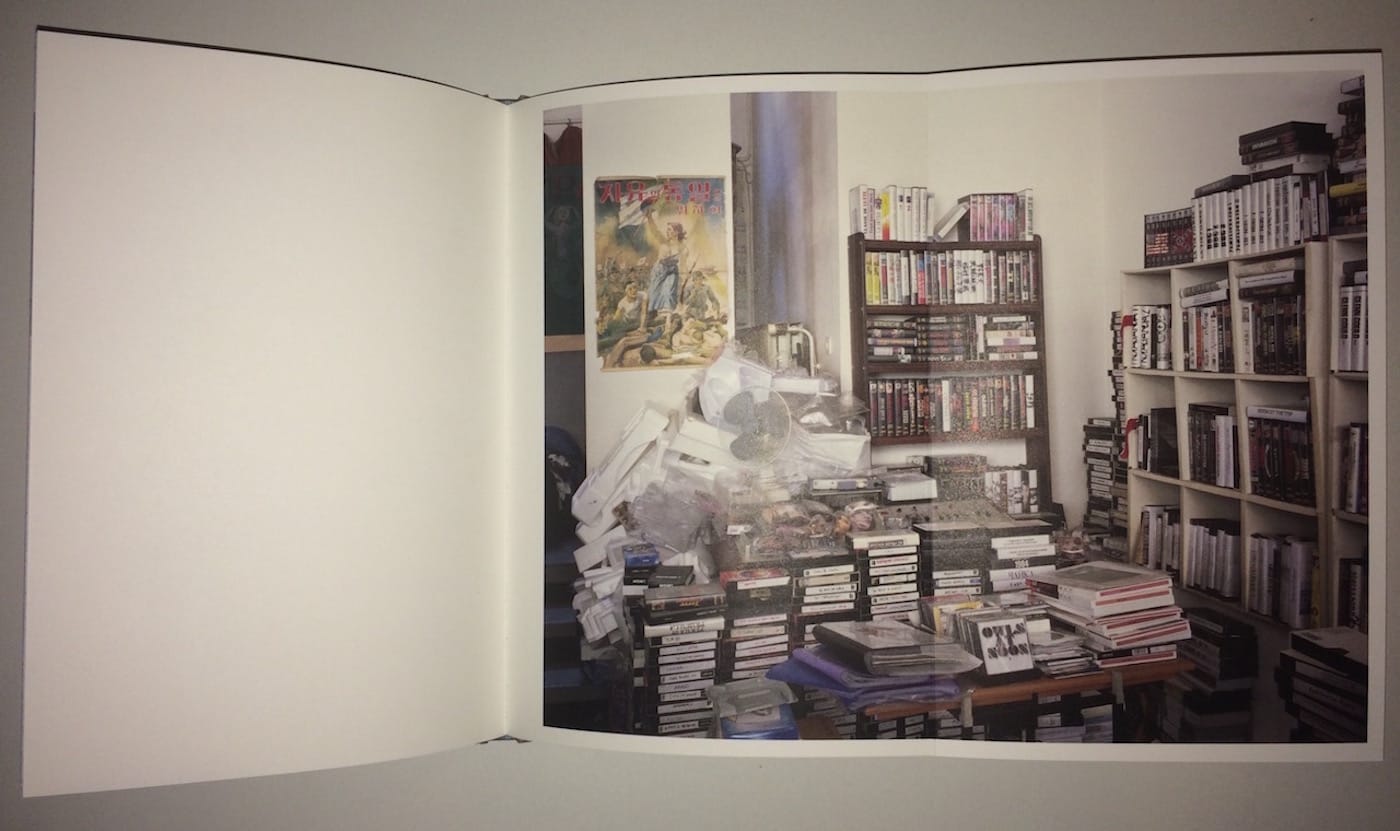

The book’s last section, “Rue Carat,” named after the street Marker lived on in the 20th arrondissement, is devoted to 10 photos Bartos took in the studio on April 4, 2007. Here, there are gatefolds of his images that reveal a kind of chaotic neatness of books, magazines, VHS tapes, DVDs, recording equipment, television sets, and cables. Shelves are filled or doubly filled, with tapes behind even more tapes. There are streaks of wires around desks that lead to boxy white computer monitors. There is a signed glossy headshot of Kim Novak from Vertigo (1958), a talismanic film for Marker that influenced La Jetée, among other works. A copy of Bartos’s Kosmos sits on one of the shelves, which Lerner points out in his introduction. A few items found in the studio that beckon this writer’s eye include: A copy of The 9/11 Commission Report (2004), VHS tapes of Perfect Blue (1997) and Ken Burns’s Civil War miniseries, and a Film Forum t-shirt. Perched throughout the studio are representations of cats and owls of various shapes and sizes.

By showcasing the space that Marker lived and worked in, Studio is a fitting tribute to a filmmaker keen on materiality. The book posits the studio as a spatial representation of Marker’s mind, complete with its organized messiness, circuitry, and vast archive. It reminds me of T.S. Eliot’s “Ash Wednesday” quote that begins Sans Soleil: “Because I know that time is always time / And place is always and only place.” Although these photos are moments frozen in time, they contain spaces that are so lived-in, it seems as if Marker is about to step into them and get to work. But that wouldn’t be Marker’s M.O. Maybe Guillaume would show up and tell us how he works.

Studio: Remembering Chris Marker is now available from OR Books.