Challenging Stereotypes by Contorting the Female Form

Hayv Kahraman’s paintings compel viewers to acknowledge the potential pleasure of viewing contorted bodies in a position of pain.

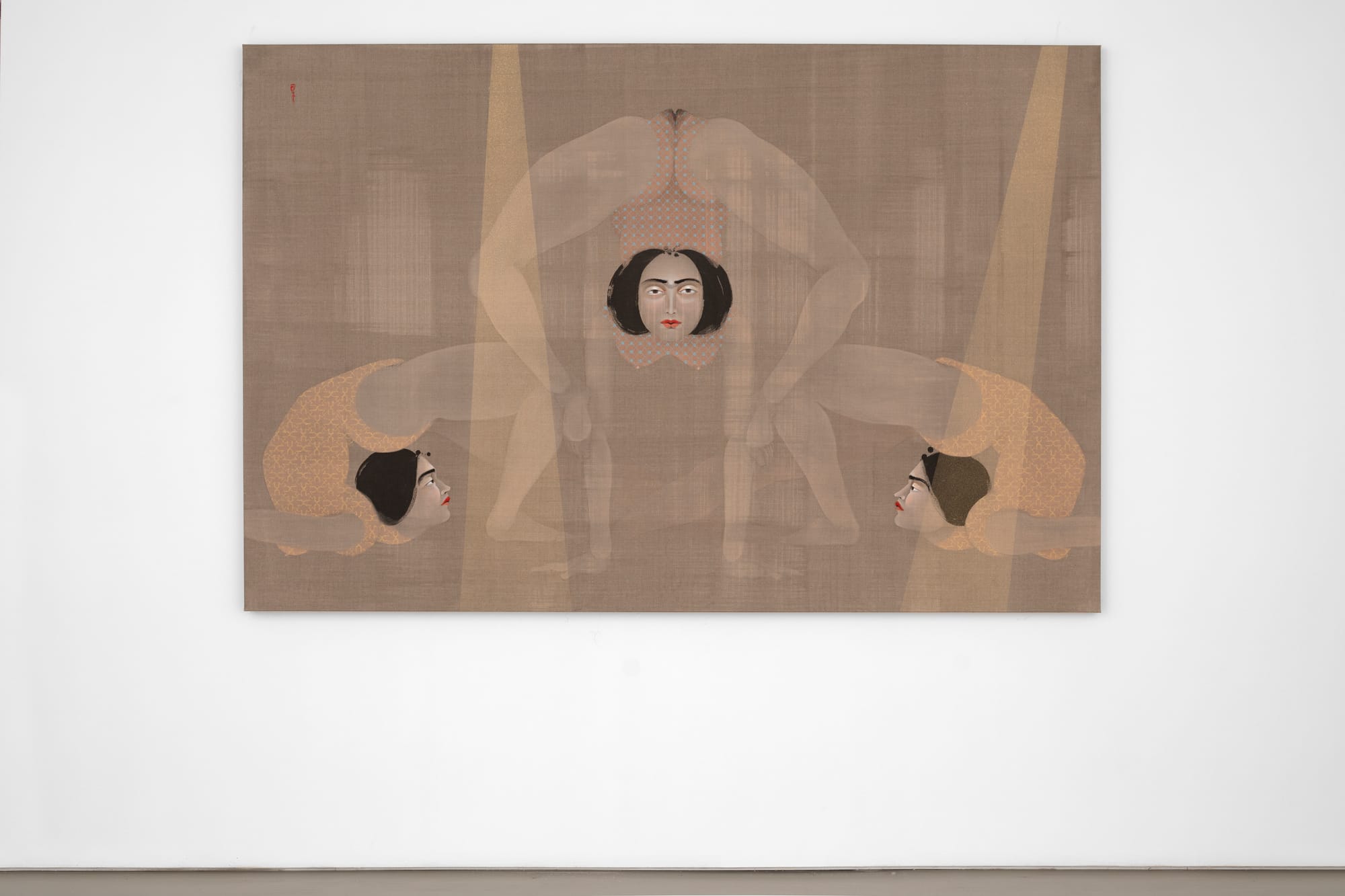

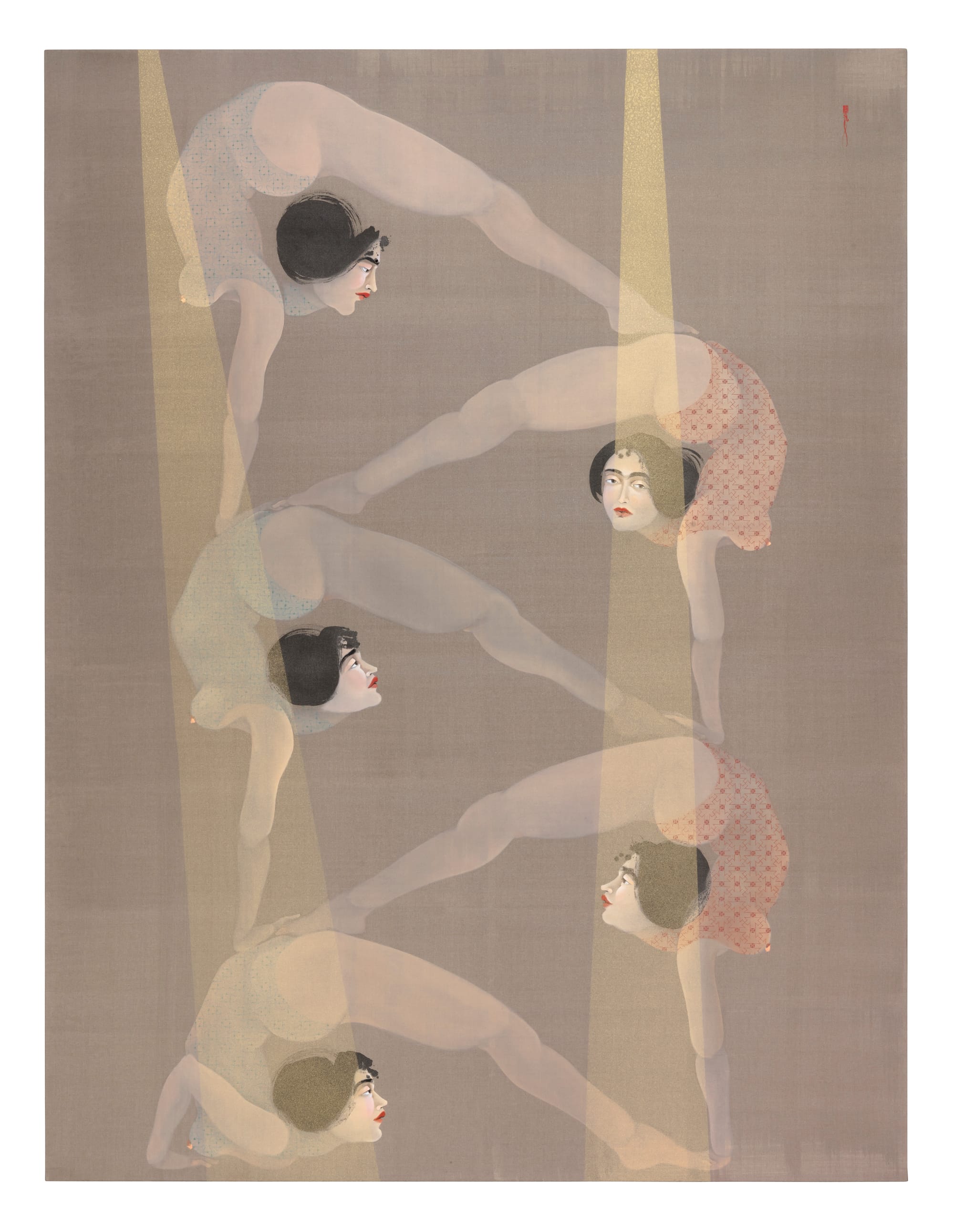

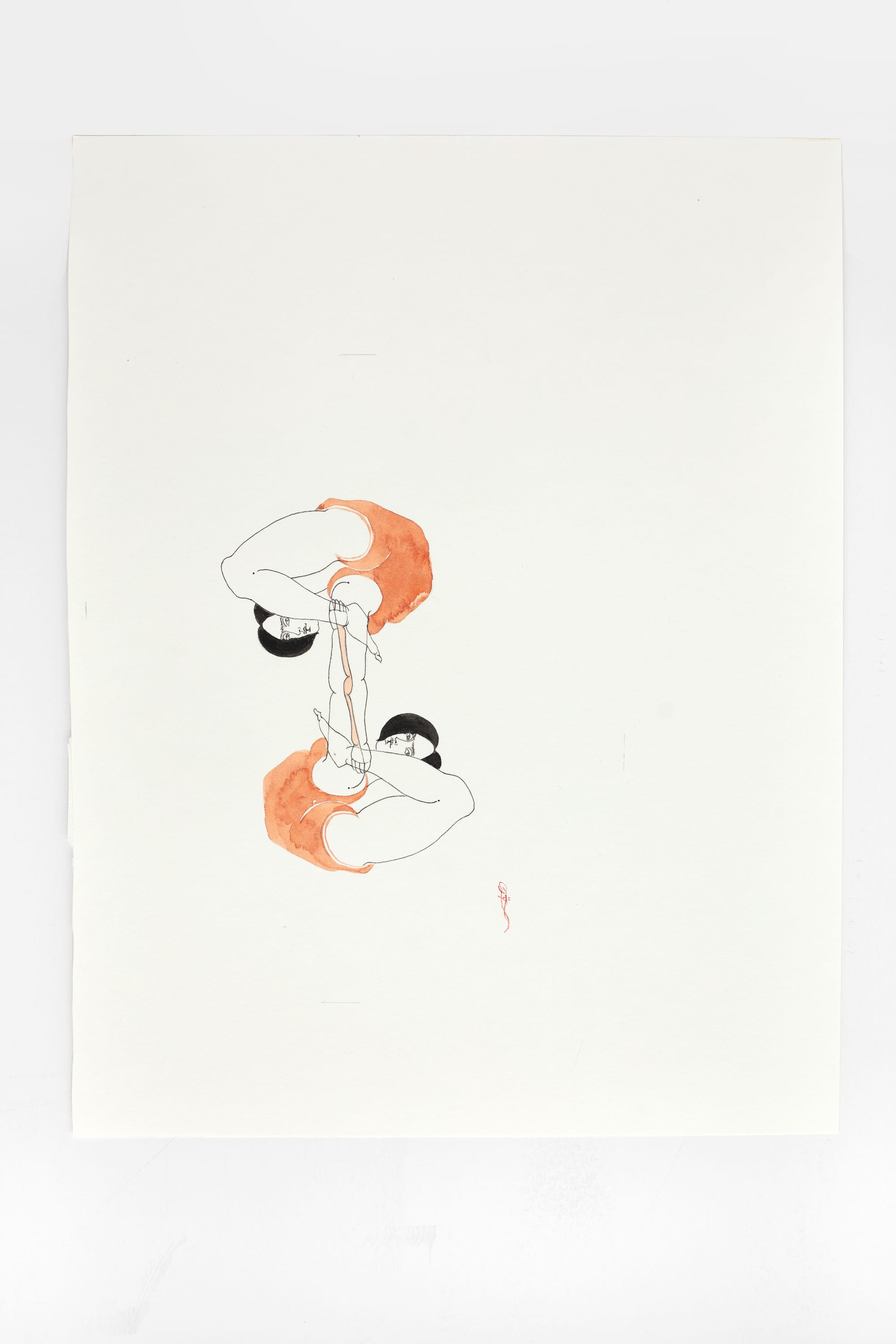

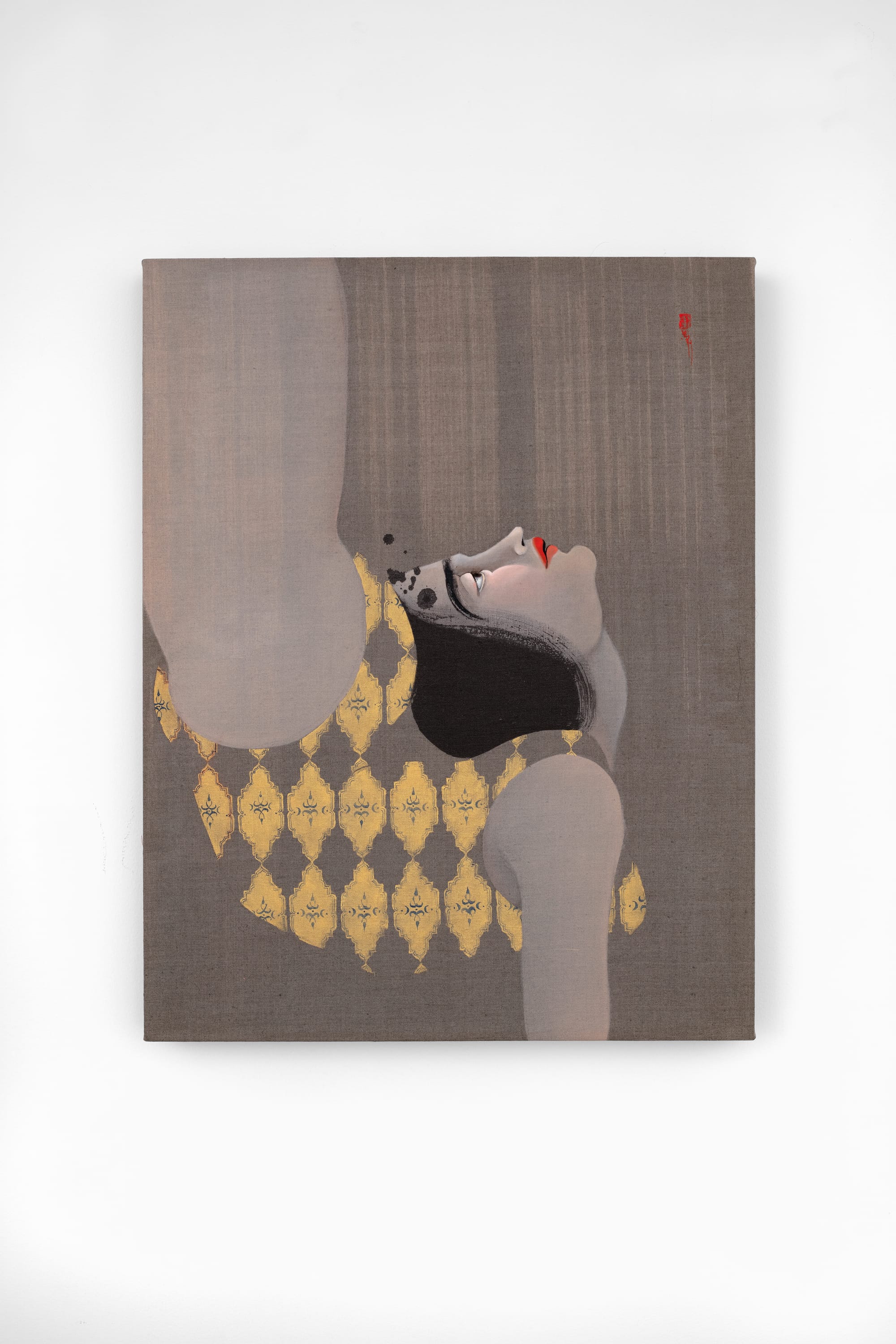

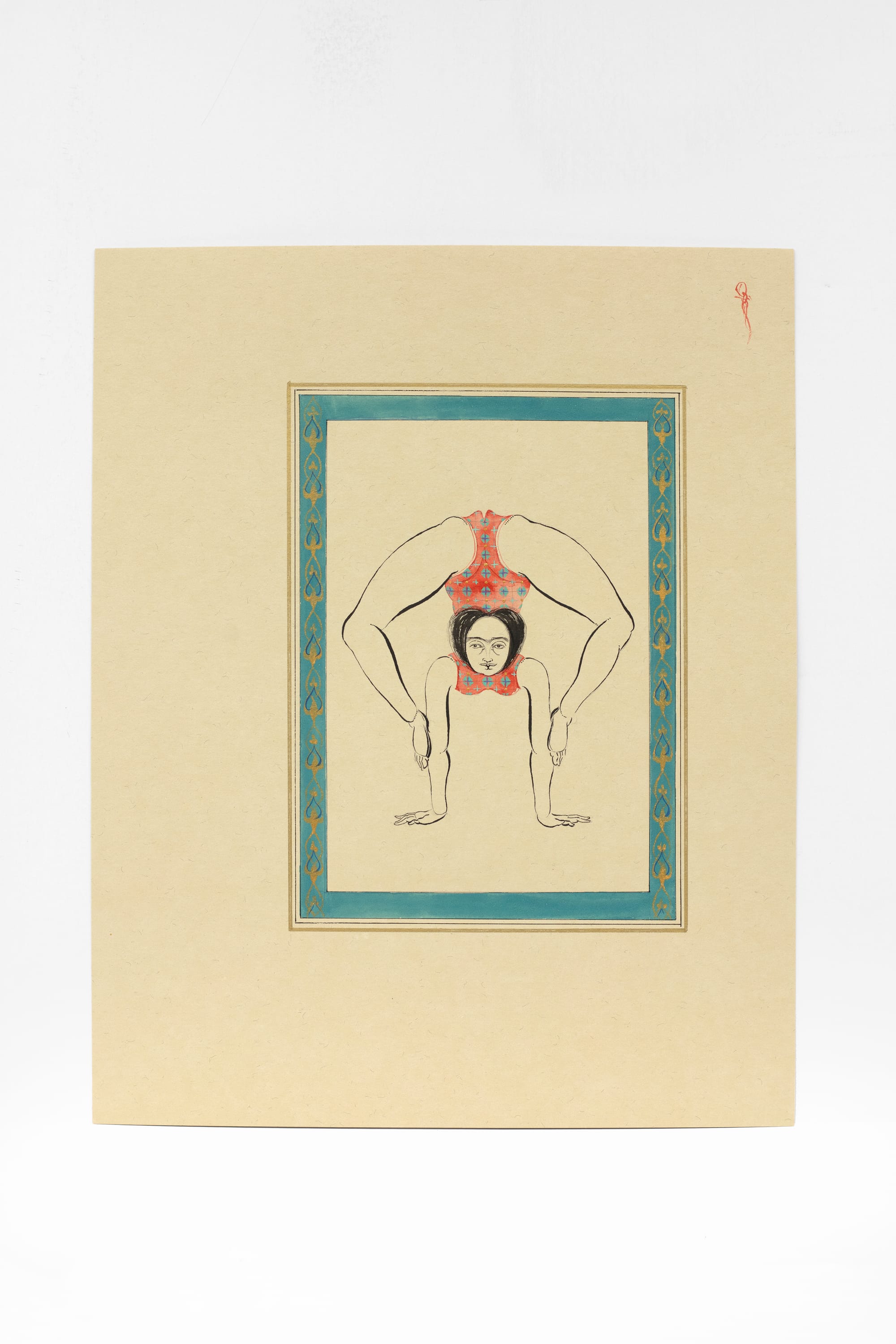

“She” is a nude female figure, the protagonist in Hayv Kahraman’s work. In a new body of work exhibited at Jack Shainman Gallery, Not Quite Human, “She” takes on the role of a contortionist, someone whose movements are non-normative, who bends her body into a variety of extreme positions. Kahraman’s paintings simultaneously convey eroticism, humiliation, and submission, while “She” confronts the viewer with a calm expression, compelling us to acknowledge the potential pleasure of viewing her body in a position of pain.

“She” performs another role as well, one Kahraman frequently explores in her work, that of the non-White, immigrant woman. Born in Baghdad in 1981, at 11 Kahraman fled to Sweden as a refugee with her family. She went on to study art in Italy before settling in the US. “She” is a response to coloniality, to Euro-centric standards of beauty (with her ivory flesh, long limbs, and jet-black hair), and to Kahraman’s personal experience of migration. Kahraman spoke with Hyperallergic about her creation of “She,” as well as trauma, coloniality, and physical and emotional pain.

Hyperallergic: Where did “She” come from? How did you create her?

Hayv Kahraman: She was born in Italy, a space surrounded by a very Euro-centric way of thinking and believing. I spent about four years in Italy and I was completely engulfed by that aesthetic and the whole spiel of the Renaissance. I think of that time as being under the spell of coloniality, of thinking and believing and wanting to become White. I was hanging out with a bunch of people who adored and studied the old techniques of the Renaissance. We would copy the Old Master paintings and we’d roam the museums all over Italy, adoring this particular aesthetic to the point where you would forget other aesthetics. That’s where this figure started emerging.

It was also a precarious time in my life. I was in my early 20s — you’re figuring out who you are. I was also in a relationship that was abusive; creating this figure gave me strength to have the voice that I did not have at the time. There were a lot of things that were screwed up personally in my life, but also it’s the spell of coloniality. [This is] what everybody — not only White kids but also Brown kids — are taught to think. That’s where “She” came out. I feel like “She” started evolving more and more as I left Italy and moved to the United States and this was a completely different space.

H: I remember going to New York and, despite coming from London, being shocked about how multicultural it is.

HK: Imagine going from London to a small suburban town 30 minutes outside Phoenix, Arizona. It’s very extreme coming from Florence. That was a massive shock. But “She” needed to be in that environment, too. “She” needed to flourish. I would turn the news on, specifically from the Middle East. I would listen to the news constantly, and you’d hear these stories of female genital mutilation happening in Northern Iraq or honor killings, and these various women who have been consumed by this extreme violence. I would grab onto these stories and really relate to them on a very personal level.

That kind of evolved into the work. The early work is almost didactically violent [in its iconography]. I needed to give her that expression from the austerity of being in Arizona, the extremity of being in that environment, and also the personal. “She” started evolving from there, going from this very violent place, and I started reading more on post-coloniality. Slowly I started realizing — particularly through Walter Mignolo’s work — that’s where “She” came from, and that’s why “She” looks the way she does. That white diaphanous flesh comes from a colonized mind. It also drove me into thinking about how I can use this knowledge to [get to] a place where I can resist that coloniality. I started shifting the way I think about things in terms of paintings; I would inject these [Euro-centric] aesthetics we are all accustomed to thinking are beautiful and then subvert that. The idea is to catch the gaze of the audience, using Renaissance tools as decoys.

H: I’m interested in the physicality of “She.” In some of your earlier work she is contorted into tight spaces of a house, and in this new work “She” is in some crazy poses. Can you tell me a little about that?

HK: It’s interesting that you mention the ones in houses because I hadn’t necessarily thought of a connection, but to connect those two makes complete sense. I did a performance in LA that involved working with 12 dancers. That made me start thinking about how to bring these figures into reality and how they can move and become alive. I started thinking about how our bodies occupy the space around us and how a twisted body can really trigger various senses in the audience.

When I was growing up in Baghdad, I went to a music and ballet school, where after school you’d have rigorous training in ballet. Because of this I was able to dislocate my shoulder and my thighbone, so I used to use this deformity to perform to my friends and family. They would look away in disgust or express a sense of pain, and that’s what ignited this whole body of work and how alterity is perceived. Then I started researching contortionism and contortionists and digging deeper into the twisting and bending of the body. Much more than the previous architectural pieces, which deal with domesticity and public spaces in a more literal way, this body of work maybe is even more violent and is very corporeal. What you have is just the body that is violently bending and twisting.

There are many ways that you can read this work, one of which is in terms of sexuality. There’s this fetishization when an audience sees a female body bending; if you Google “women contortionists” you’ll see a lot of pornography. And with eroticization there’s exoticization, so you have this exotic freak female who is dangerous, performing in this circus space. You can delve into that way of looking at the work, but there’s also the idea of contorting oneself to fit within some sort of larger system of power and this has more to do with ideas of assimilation and coloniality and [W.E.B.] Du Bois’s “double consciousness,” where he talks [in The Souls of Black Folk, 1903] about looking at yourself through the eyes of the other. I love this phrase. In this case the other is the Global North, so looking at yourself through the White patriarchy, if you will. As an immigrant or refugee, I feel extreme affinity with this way of thinking, moving to Sweden, being Brown, and so different from everyone around me. The way I knew how to survive that was to assimilate, it was to become what the Swedes wanted me to become. In order to become that I needed to learn what they wanted me to become, to understand the way that they looked at me.

H: When I look at the positions that “She” is in within this new body of work, it seems quite painful, but her face appears as though she’s not bothered about it. Do you ever think about the idea of pain?

HK: You’re right, there’s a sense of numbness there. The numbness comes from the deception of yourself, this kind of erasing or training yourself to not feel. I feel like once you train yourself to become somebody else, you lose who you are or who you think you are, at least. A coping mechanism is this kind of glazing over things. If you were able to allow yourself to feel pain, it is so extreme and traumatic that you might not be able to survive that pain. My therapist says you need to break in order to heal, and in order to break you need to feel pain.

H: But a lot of people go through trauma and never speak of it their whole lives.

HK: Exactly. I feel like the figures have both sides there. There is a sense of numbness but there’s also a sense of resistance. The fact that they’re returning the gaze is, in itself, very powerful.

H: Even their positions are very powerful. The fact that they’re able to bend so dramatically and can physically lift each other up — their posture is very powerful.

HK: There’s an interesting kind of polarity there, right? Because you have this extreme kind of humiliating, submissive way of contorting your body, but then there’s also power in that. I think that power comes from that very sense of otherness, because you’re looking at her and you’re like, “How does she do this. I can’t do this, this is extremely powerful, but, oh my gosh, isn’t it painful?”

H: So it’s like they’re tricking the viewer but they’re also tricking themselves.

HK: Yes, exactly.

H: Is there anything else you wanted to talk about?

HK: I liked how you talked about pain, because when you talk about healing that colonial wound, pain is involved. I think subconsciously that is why I was gravitating towards these images of contortionists, because I would feel that [pain], and ultimately, within all of my work there’s this sense of repair and mending, of mending this colonial wound, of being othered [as] a refugee-cum-immigrant, and having to survive those extreme places.

Hayv Kahraman: Not Quite Human continues at Jack Shainman Gallery (513 West 20th Street and 524 West 24th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) through through October 26.