Ana Mendieta’s Injured Earth

Although many of her earthworks have been erased by time, the late Cuban-American artist’s interventions attest to her continued presence, etched into the land.

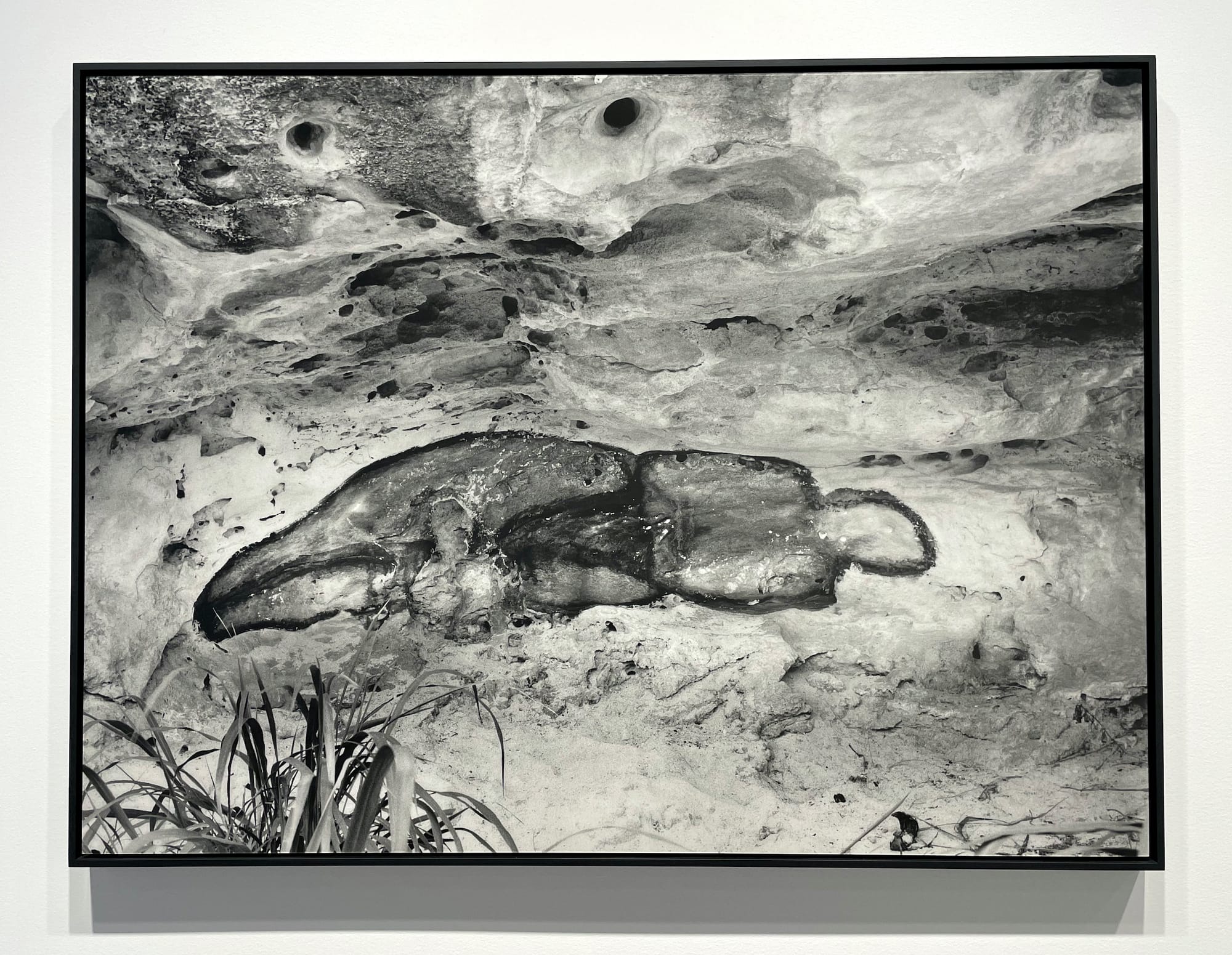

In a 2021 interview about Ana Mendieta: Fuego de Tierra, the film’s co-director, Nereida Garcia-Ferraz, spoke about locating one of the artist’s “earth-body” artworks, as she called them. “The day we found the Black Venus behind a natural veil of foliage was magical. Nature had protected her work.” Garcia-Ferraz is most likely referring to “La Venus Negra” (1981), an elemental feminine figure carved into the surface of a cave in Cuba’s Jaruco State Park. A photograph of this piece is one of several such images, including those from her famed Silueta series (1973–80) and her subsequent Rupestrian Sculptures (1981) works, in Ana Mendieta: Back to the Source at Marian Goodman Gallery.

The silhouettes in the photographs — pressed into a grassy field, floating within a body of water, set in mud and then filled with blood-red pigment — convey absence upon first glance. That makes sense: Mendieta was displaced from her birthplace of Cuba at the age of 12 as part of Operation Peter Pan, a program that relocated children to the United States without their parents during the Cuban Revolution; she ended up in an orphanage and foster homes in Iowa, only returning to visit Cuba as an adult.

Yet Garcia-Ferraz’s story of discovery casts a different light on “La Venus Negra” and related works by attesting to the artwork’s continued presence — a trace of the artist that remained long after she and many others have come and gone from the spot.

Mendieta’s trace is everywhere in her art. In the poetic “Ñañigo Burial” (1976), named for an Afro-Cuban religious brotherhood, 47 black candles compose the outline of a feminine form, filling in the body as they melt. And though many of her earthworks have been erased by time, her intervention subtly alters the way that stone erodes or vegetation grows.

Her performances were more collaborations with the earth than the actions of an individual taking place upon or within it; she said of the Siluetas, “It is a way of reclaiming my roots and becoming one with nature.” The work can also speak to the human imprint on the Earth in the form of those artificial borders that are destructive to both nature and the people who are exiled from one territory or refused entry into another. The only boundaries in her pieces are those that delimit the body, and they are no more than ephemeral evidence of a meeting between the human and the land, one living entity and another.

That’s not to disregard the political dimensions of the work in favor of a utopian communion with nature. For instance, a text on view for an exhibition in Mendieta’s lifetime about the “Black Venus” tells the story of a Black woman in early 19th-century Cuba who passively refused enslavement by colonial Spaniards. Though “La Venus Negra,” and its Iowa predecessor, “Black Venus” (1980), can just as readily refer to the story of Sarah Baartman, a Khoikhoi woman (sometimes called “Black Venus”) who was abused and forced into a traveling sideshow in the early 19th century, and to Mendieta’s own forced exile as a child.

Along with the photographs, drawings, installation, and ephemera that fill the gallery’s two floors, 10 films alternate in two screening rooms. Most are related to the Silueta photographs. “Grass Breathing” (1975) stands out because Mendieta is truly absent from view; instead, a patch of grass in a green Iowa field vibrates, first almost indiscernibly, but finally, heaving like a body gasping for air. Though the artist lies beneath it, causing the movement, it comes across to me as the ultimate expression of an injured Earth. There’s much more that can be said of Mendieta’s art, but as humans increasingly destroy the natural environment, this piece says so much that needs to be heard right now.

Ana Mendieta: Back to the Source continues at Marian Goodman Gallery (385 Broadway, Tribeca, Manhattan) through January 17. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.