Fra Angelico Etched the Divine in Stone

The veiled symbolism of the artist's marble and stones has largely flown under the radar, but these mystical depths are too profound to miss out on.

FLORENCE, Italy — As Italy celebrates its largest Fra Angelico retrospective since 1955, at the Palazzo Strozzi and Museo di San Marco, it’s easy to overlook the small details in favor of the grandiosity of the art and the feat of bringing it together in one place. But look at the marble surface on which John the Baptist stands in the Perugia Altarpiece. The veiled symbolism of the veined stones has flown under the radar in most major English-language reviews of the exhibition. But these mystical depths are too profound to miss out on.

One of the great questions in Fra Angelico studies is how many intricate layers of theological symbolism he wove into his art, gleaned from his erudite studies as a Dominican friar. The theological evolution, ushered in by the Franciscans and Dominicans, demanded new styles to meet new spiritual needs, as scholars including Donal Cooper, Joanna Cannon, and Holly Flora have recently begun to explore. The significance of blood, gold, and emotional displays are just the tip of the iceberg.

Designating a former monastery, the Museo di San Marco, as the exhibition’s second venue both spotlights the many immovable frescos Fra Angelio painted there for personal devotion in the monk’s cells — for instance, the "Mocking of Christ" (1439–41) — and invites attention to the devotional aspects of the works. Yet the curators avoided one of the most hotly contested questions in Fra Angelico studies. Why did the artist go to such great lengths to incorporate marble and stone details into so many of his works?

In the "Montecarlo Annunciation Altarpiece" (1432–35), the marble panel and floor are visually commanding enough to interfere with the rest of the composition, and distract attention from Mary and Archangel Gabriel. Spectacular to behold, the shimmering stones — simultaneously evoking both fire and water — tempt comparisons with abstract painting. Such “zones of stone” feature prominently in over half the works in this show, begging the question: Why would a Dominican friar who took a vow of poverty take such pains to paint ornamental diversions without a nuanced and widely accepted theological justification?

Exploring the meaning of marble and stone can totally change perceptions of several works on view in Florence. In 1990, the french art historian and philosopher Georges Didi-Huberman set out to answer the riddle of the marble’s iconography in his landmark book Fra Angelico. Dissemblance et figuration, later translated by Jane Marie Todd into the English Dissemblance and Figuration.

Didi-Huberman was struck by the mystical meanings ascribed to stones and crystals in a now largely forgotten treatise by one of the 14th century’s most revered Dominicans, Giovanni di San Gimignano. In Book 2 of Liber de exemplis et similitudinibus rerum (Book of Examples and Similitudes), circa 1300, the Dominican writes that all stones are figures of God’s love because God’s love is as solid as a stone; stones represent a transmutation of the original clay, and a sacred virtual fire; marble’s multiplicity of colors exemplifies the principle of beauty. San Gimignano even compares Christ to a Chrysolite that shimmers like fire but resembles the sea. Didi-Huberman hypothesized that Fra Angelico pictorialized these analogies by interspersing Mary, Jesus, and the Saints with brightly colored stones, which Giovanni di San Gimignano believed could inspire the faithful.

The "Montecarlo Annunciation Altarpiece"’s marble elements support this reading. Similarly, the "Annalena Altarpiece" (1445) abounds with painterly marble: A richly veined amber slab lay beneath the Virgin's flowing robe, with narrow slabs of green and pink marble underneath it. Niches with bright semi-circular pink marble panels float above the heads of the saints. Embedded in that familiar formula of enthroned virgins flanked by saints, Fra Angelico could be nodding to monks and priests in the know about secret mystical meanings of marble and stones.

Fra Angelico went out of his way to feature rocks in other compositions as well, many included in this exhibition. One of the most explicit examples is the small predella panel of St. Francis receiving the Stigmata. Now in the Vatican collection, it was originally part of the so-called Franciscan Triptych, which has been temporarily reassembled here. The rays of light from the angel mirror the diagonal crag beneath it. Those cliffs dominate the composition far more than in comparable depictions by Giotto, Gaddi, and Sasetta, who all relegated rocks to the background. Was Fra Angelico alluding to St. Paul’s frequently quoted metaphor that Christ is our rock in this work? Is this a visual echo of Giovanni di San Gimignano’s idea that God’s love is as solid as stone?

Fabio Barry's recent book on the history of marble in art posits the term “lithic imagination” to retrieve what was once the prevailing belief that something divine or astral dwelled within marble. Sterile geological definitions may be today's default, but it’s important to guard against projecting it back onto old masters who saw marble differently. Stones are downplayed in the wall didactics of the retrospective, and trivialized as bracketed mentions and footnotes in the catalog, while Didi-Huberman’s book —the most disruptive and provocative study of Fra Angelico’s iconography to date — is effectively absent. It’s an egregious error of omission not to address his ideas more directly and substantially.

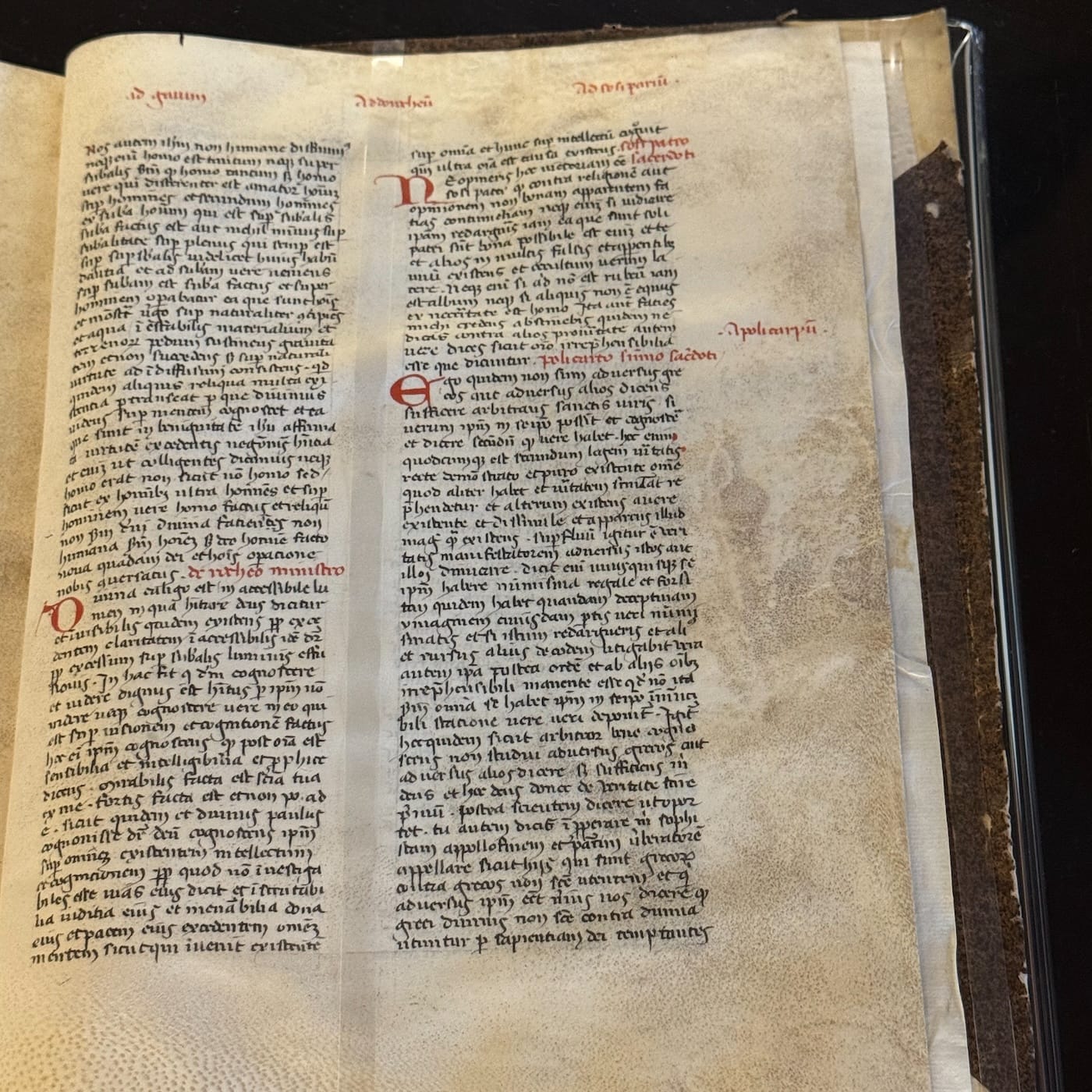

What the curators have featured, in the monastery's former library, is a 14th-century manuscript of Pseduo-Dionysius the Areopagite. Giovanni di San Gimignano connected his own marble, stone, and crystal metaphors with the notion of dissemblance advanced in this manuscript.

Pseudo-Dionysius cautioned that if the divine is truly inexpressible, then no concept can adequately represent it. The more effective a sacred symbol seems to be, the greater the risk of masking the ineffability of the divine. Pseduo-Dionysius the Areopagite instead encouraged dissimilitude — the use of unorthodox metaphors, those that do not seem to resemble the divine as commonly understood, in order to precipitate a crisis of interpretation.

Accordingly, Didi-Huberman argued that Fra Angelico was approaching marble and stone as discordant symbols, accepting Giovanni di San Gimignano invitation to embrace rocks for their sacred dissimilitude. This opens up a Pandora's Box of possibility that everything in a Fra Angelico painting might mean something else.

In her famous 1376 letter, St. Catherine of Siena urged Stefano Maconi to “be who God meant you to be, and set the world on fire.” As Fra Angelico stepped into his authenticity and maturity as an artist, he continued to incorporate far more stones and marble than his predecessors. By downplaying this aspect of the art in Florence, the curators and critics played it safe. As a studious Dominican friar, Fra Angelico imbued his paintings with the divine stones and marble he admired, setting the world on fire.

Fra Angelico continues at the Palazzo Strozzi (Piazza degli Strozzi, Florence, Italy) and the Museo di San Marco (Piazza San Marco, 3, Florence, Italy) through January 25. The exhibition was curated by Carl Brandon Strehlke, with Angelo Tartuferi and Stefano Casciu for the Museo di San Marco.