Spain’s Cosmic Mother of Modernism

Maruja Mallo viewed herself as an extension of her modernist paintings, in which female energy is a conduit for natural and even otherworldly forces.

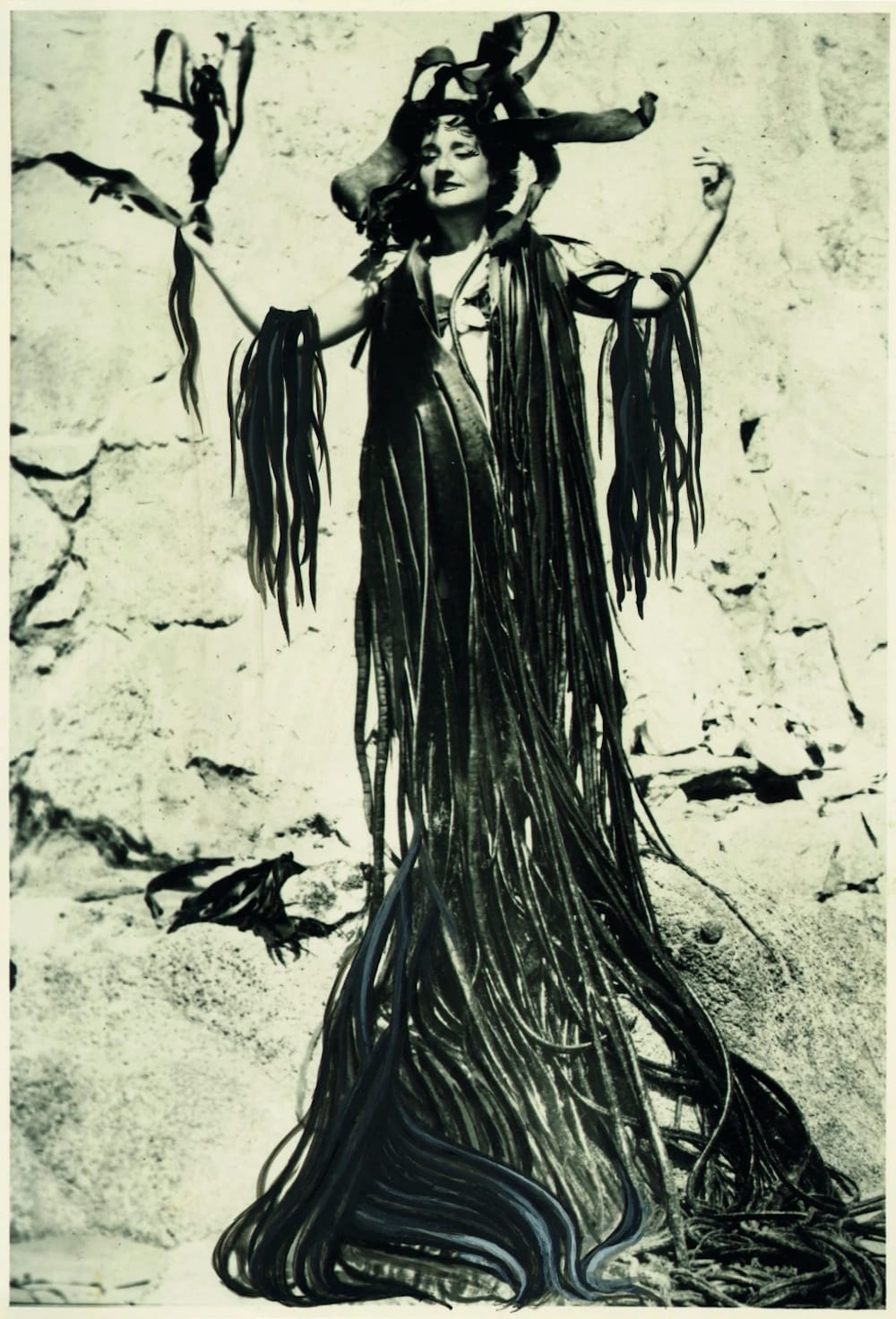

MADRID — The most famous portrait of Maruja Mallo depicts the artist covered from head to toe in seaweed. She is crowned and draped with long, rope-like strands of kelp, her arms raised triumphantly like an all-powerful marine goddess. This unconventional photograph, snapped in 1945 by the poet Pablo Neruda on a Chilean beach, was no doubt carefully orchestrated by the Spanish artist, who viewed herself as an extension of her unique work, where female energy is a conduit for natural and even cosmic forces.

Maruja Mallo: Mask and Compass at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía is the Mallo's largest retrospective to date. Featuring 100 paintings, some 70 drawings, and 100 archival documents — including the aforementioned photo — the expansive presentation traces her entire career trajectory. Curator Patricia Molins has taken great care in elaborating a wide view of the artist’s exceptionally varied oeuvre; in addition to her major two-dimensional artworks, we’re privy to her published writings, photographic self-portraits, and meticulous, quasi-scientific notebooks, as well as recreations of her lost set designs and ceramic works.

Born Ana María Gómez González in Viveiro, Galicia, in 1902, Mallo studied art at the prestigious Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid. There, she befriended art and literature luminaries like Luis Buñuel, Salvador Dalí, and Federico García Lorca, and became part of the groundbreaking Generación del ‘27 group, which produced avant-garde writing, poetry, and art in Spain in the 1920s and ’30s.

Early in her career, she was associated with other influential art movements and collectives, including the Surrealists, the Escuela de Vallecas, and the Grupo de Arte Constructivo. Ultimately, though, her vision was so completely distinct, and her work so idiosyncratic, that she became alienated from her peers, which perhaps accounts for her lack of name recognition outside of Spain.

Three decades after her death, the exhibition enshrines Mallo as one of the most singular and innovative artists of the 20th century. It also makes a case for her as an important representative of women in art and modern life. Her defiant early paintings portray nude or nearly nude athletic women confidently swimming or bicycling, activities that mainstream Spanish society saw as immodest and improper for women at the time. (A photograph of Mallo’s portrait of a friend wearing a bathing suit, which was promptly destroyed by the model’s indignant father, is on view to underscore social standards of the time.)

Mallo’s vibrant Verbenas (Street Fairs) series — reunited for the first time since they were originally exhibited in Madrid in 1928 — are carnivalesque celebrations of fast-paced urban life that center active, modern women. In “La verbena” (1927), for example, two smiling women in short, form-fitting dresses step boldly out of kaleidoscopic scenes of revelry and toward the viewer; their open arms seem to lead the energetic parade of life itself.

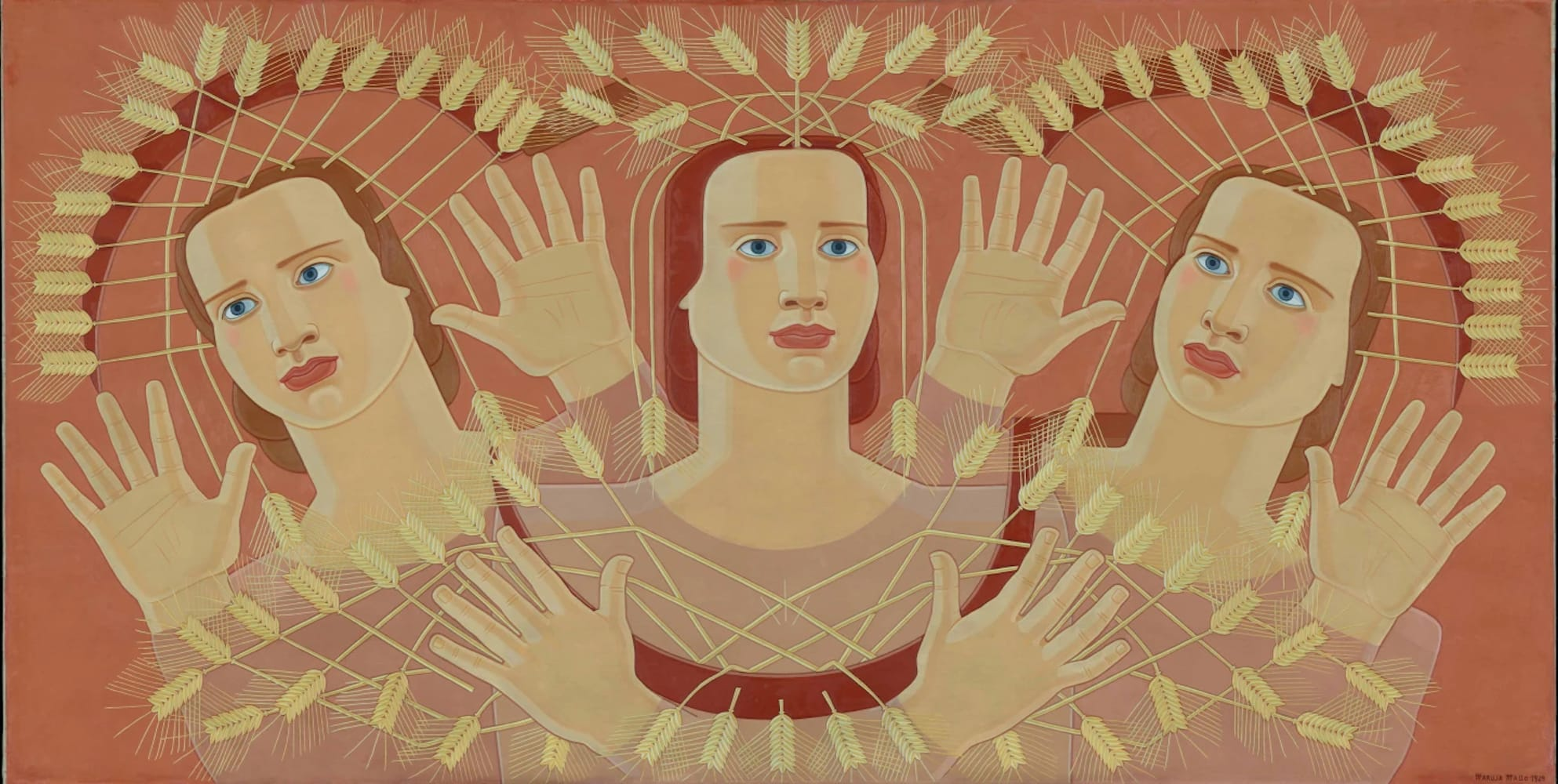

These works, inspired by popular art, cinematic montage, and theater, give way to the artist’s Cloacas y Campanarios (Sewers and Bell Towers) paintings. The arresting images were made after her breakup with poet Rafael Alberti, yet their motifs — dark, desolate landscapes populated only by trash, skeletons, and excrement — seem to eerily predict the coming devastation of the Spanish Civil War. When the conflict broke out, she was sketching local fishermen in the small coastal Galician town of Bueu. She was forced to flee to Portugal, and later to Argentina, where she settled in 1937. But these Galician drawings eventually became the foundation for one of her most significant series, La religión del trabajo (The Religion of Work). In these monumental paintings, heroic female figures wield scythes, sheaves of wheat, nets, and fish. For instance, the large-scale oil painting “Canto de las espigas” (1939) shows three identical women, each with raised hands and framed by stalks of wheat that intersect delicately behind their heads like halos. Here, as in the photo of Mallo covered in seaweed, women are statuesque and self-sufficient. They symbolize an eternal and fortifying link to the natural world. By contrast, men are not present, nor do they seem necessary. All compositions from this series are precisely mapped according to theories of visual harmony and precision that would preoccupy the artist for the rest of her career (hence the word “compass” in the exhibition’s title).

In Argentina, Mallo met fellow artists in exile like Jorge de Oteiza and Luis Seoane, but it was South America’s flora, fauna, and unique blend of religions, cultures, and people that stimulated her the most. Shells and flowers resemble reproductive organs and sex acts in her sensual series Las naturalezas vivas (Living Nature Works) while a fascinating group of portraits feature sitters of ambiguous race and gender, reflecting the artist’s belief in universality rather than divisions between people, plants, and the cosmos. In fact, Mallo incorporated mathematical concepts like geometry into her art because they enabled her to manifest her faith in a highly organized and universal order.

The show’s most enigmatic and haunting works are a number of paintings that portray masks floating above beaches, acrobats, and butterflies. Created in the 1940s and 50s before her return to Spain in 1965, they are pervaded by feelings of transformation and alienation, which seem to speak to Mallo's complex position as an exile and a lifelong nonconformist, as well as her interest in psychoanalysis.

By the 1970s, Mallo had discarded the earthly plane entirely in her art. Her final bodies of work, Moradores del vacío (Dwellers of the Void) and Viajeros del éter (Ether Travelers), present diatom-like entities that appear to be microscopic and mystical at the same time. Perhaps it’s fitting that an artist whose creations were otherworldly in her day looked increasingly to space as a site of inspiration. Through this exhibition, she might finally secure her place in the earthly canon of modernist masters.

Maruja Mallo: Mask and Compass continues at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (Calle de Santa Isabel, 52, Madrid, Spain) through March 16. The exhibition was curated by Patricia Molins.