The Glitter and Doom of Lee Miller's Vision

From her collaborations with Man Ray to her work as a WWII photographer, the artist retained a mix of defiance, poignance, and brazen, oddball humor.

LONDON — Who was Lee Miller? There were two of her, really.

One was the photographer featured in a current retrospective at Tate Britain, who was born in New York in 1907, moved to Paris in 1929, and then to London. She went to Europe in restless pursuit of the desire for others to believe in everything she had to offer — her multiple gifts as an artist, for example.

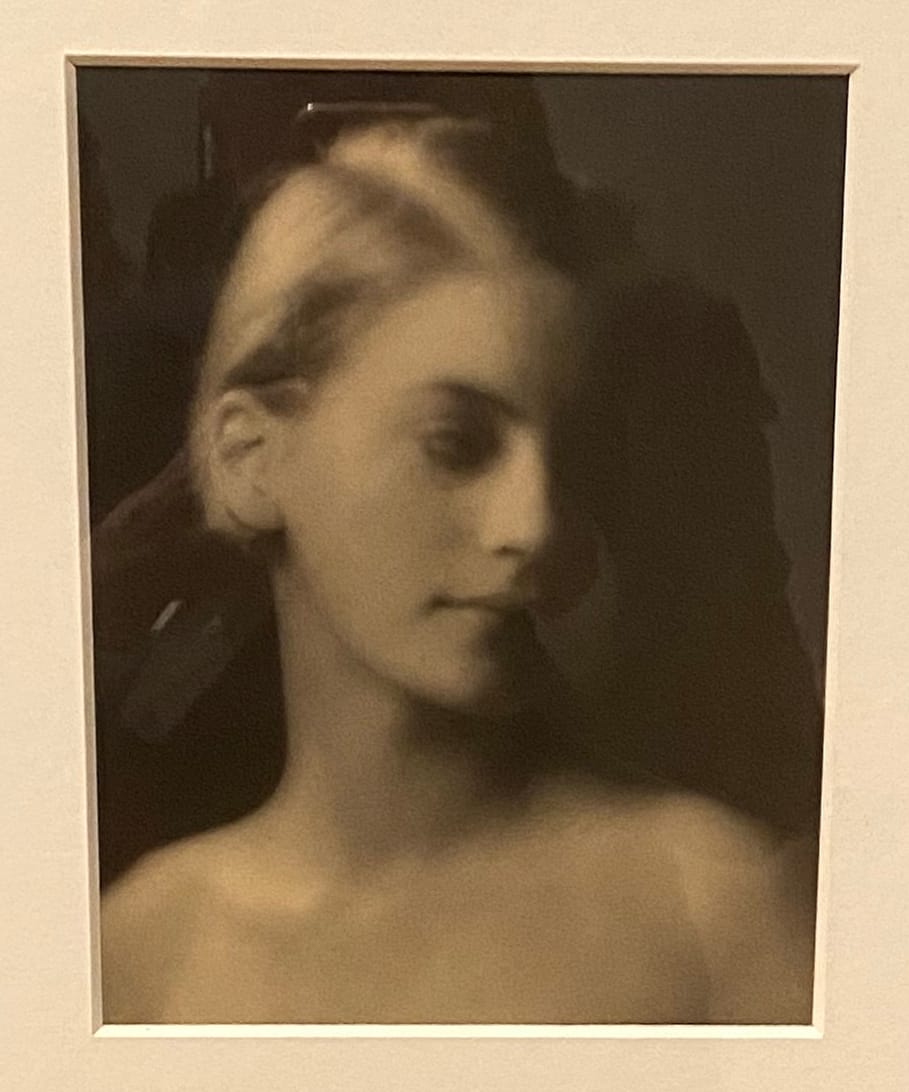

The other was a model. Modeling in New York in the 1920s was her opening gambit. She had the looks and poise to succeed and her talents were quickly recognized. She arrived in Paris in the flapper era — sinuously tall, her hair close-cropped. My goodness, that wonderful androgynous look! She seemed made for the part — and the historical moment.

But modeling had its limitations. Was there not too much idle self-regard in that ready capitulation to another’s camera? Perhaps. She had too much energy and ambition to be someone else’s glamorous image of the passing moment.

So she went to work for Man Ray in Paris. She modeled for him — but it was much more than that. They worked together on Surrealist experimentation. She took pictures and did some odd freakery on them: solarization, deep shadow, the isolating of strange and provocative detail. They collaborated, but unsurprisingly she did not get full credit for what she did. He tended to claim that what emerged from the studio of Man Ray (emphasis on Man?) was his. She needed to wrest back control, to be the one calling the shots.

She returned to London in 1939 and worked as a fashion photographer for Vogue magazine. The shadows of war loomed over. Her art began to take on a new urgency, and to strike a note that any small and embattled country needs to strike if it is to retain its morale, its need to fight back against a dangerously predatory enemy.

She made images of women in the not-so-glamorous clothing that wartime demanded, but she did it with style and aplomb — in Miller’s hands, the stuff of war looked positively alluring. In addition to the working women, she photographed the London Blitz. In one photograph, a bomb-blasted gap in a London terrace looks like a conscious act of framing. She posed a model in a ruined street, as if a fleeting instance of beauty could defy the casual barbarism of war. She showed her great courage in roaming those dangerous streets to produce images that were odd, spirited, and spirit-lifting, too — and possessed a quality of defiant humor.

Following this, Miller went to Europe to work as an accredited war correspondent with the US Army. Nothing fazed her. She was determined to stare hard into the face of the awful reality of evil on its filthy rampage.

She had her friend, Life magazine photographer David Scherman, photograph her bathing in Hitler’s bathtub at his abandoned residence in Munich the day of his suicide in Berlin — that old mix of defiance, poignance, and brazen, oddball humor. She went to the Nazi concentration camps and photographed the worst things that any human being might ever witness. This gallery has a warning notice: not for children. I was told not to photograph her images so I can’t show you what she saw.

Lee Miller pushed herself to the limits and beyond, and suffered for it. In later life, she returned to a farm in Sussex and became a gourmet chef, leaving behind the nightmares that she captured on film.

Lee Miller continues at Tate Britain (Millbank, London, England) through February 15, 2026. The exhibition was organized by Tate Britain in collaboration with the Musée d'Art Moderne de Paris and the Art Institute of Chicago and curated by Hilary Floe and Saskia Flower.