The Shapeshifting Sculpture of Diane Simpson

From one angle, her sculptural constructions appear deep, but from another flat; here they look angled, there not.

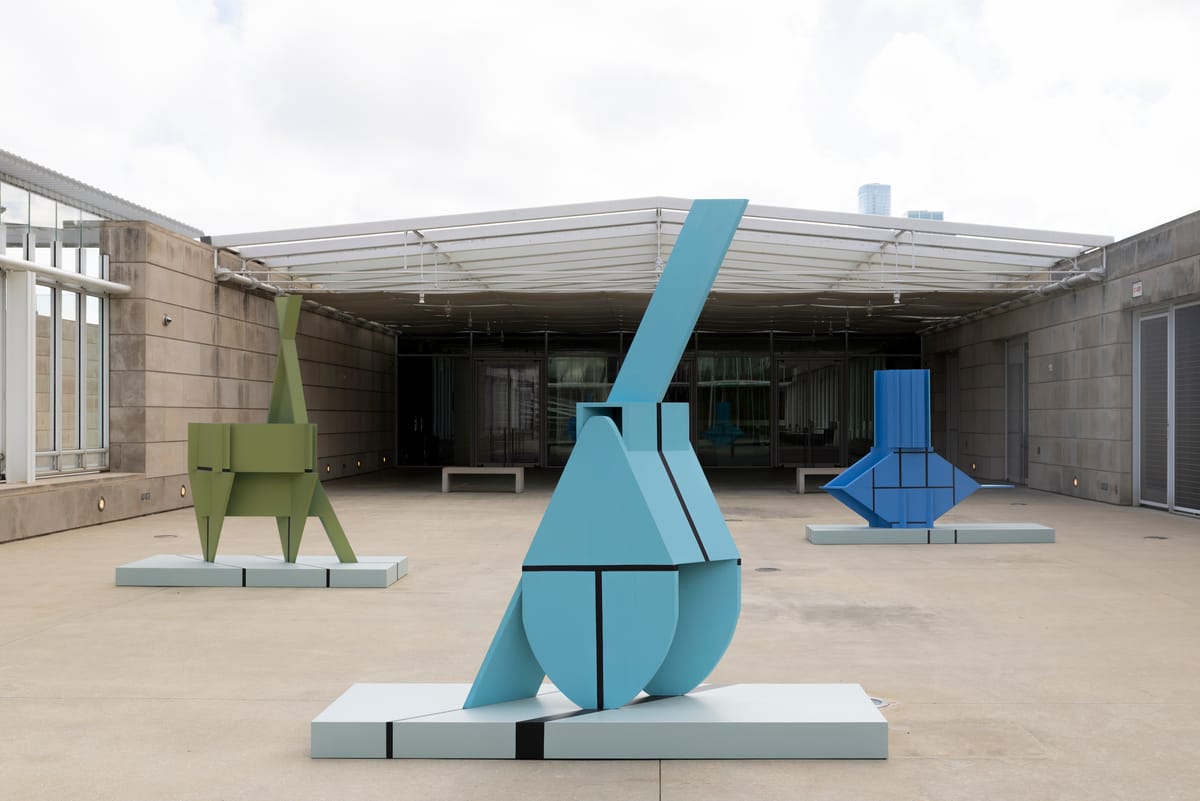

CHICAGO — Seeing a sculpture by Diane Simpson is nothing like seeing a sculpture by any other artist. Chicagoans can currently experience this in person on the rooftop terrace of the Art Institute of Chicago, where her first three outdoor sculptures ever are on display, and at the gallery Corbett vs. Dempsey, which features two classics in a group show.

Sculpture in the round traditionally proceeds in logically continuous increments. As you circle a baroque Bernini or modern Rodin or postmodern Charles Ray, you and the sculpture are on the same three-dimensional plane of existence. Not so with a Simpson. From one angle it appears deep, but from another flat; here it looks angled, there not. The different sides of her constructions simply do not agree with one another. The technical reason for this confusion is that Simpson first finds inspiration in a three-dimensional object — samurai armor, chairs, and bonnets have all been prompts — and then drafts some aspect of her source using isometric projection, a drawing style common in engineering diagrams and geometry classes, as well as historical Chinese and Japanese scrolls. It employs parallel projection and consistent angles, such that objects at a distance do not appear smaller than close ones, as in single-point perspective. So far so good. But then Simpson does something crazy — she transposes her drawing into a three-dimensional sculpture while maintaining those angles and parallels, thereby creating an artwork that makes no sense in real space. Encountering her constructions is like walking around inside a drawing. Other writers have had great fun with comparisons, my favorite being to the scene in Pixar’s Inside Out, when Bing-Bong, Sadness, and Joy take a shortcut through the world of abstract thought and temporarily become fragmented, deconstructed, two-dimensional, and then linear.

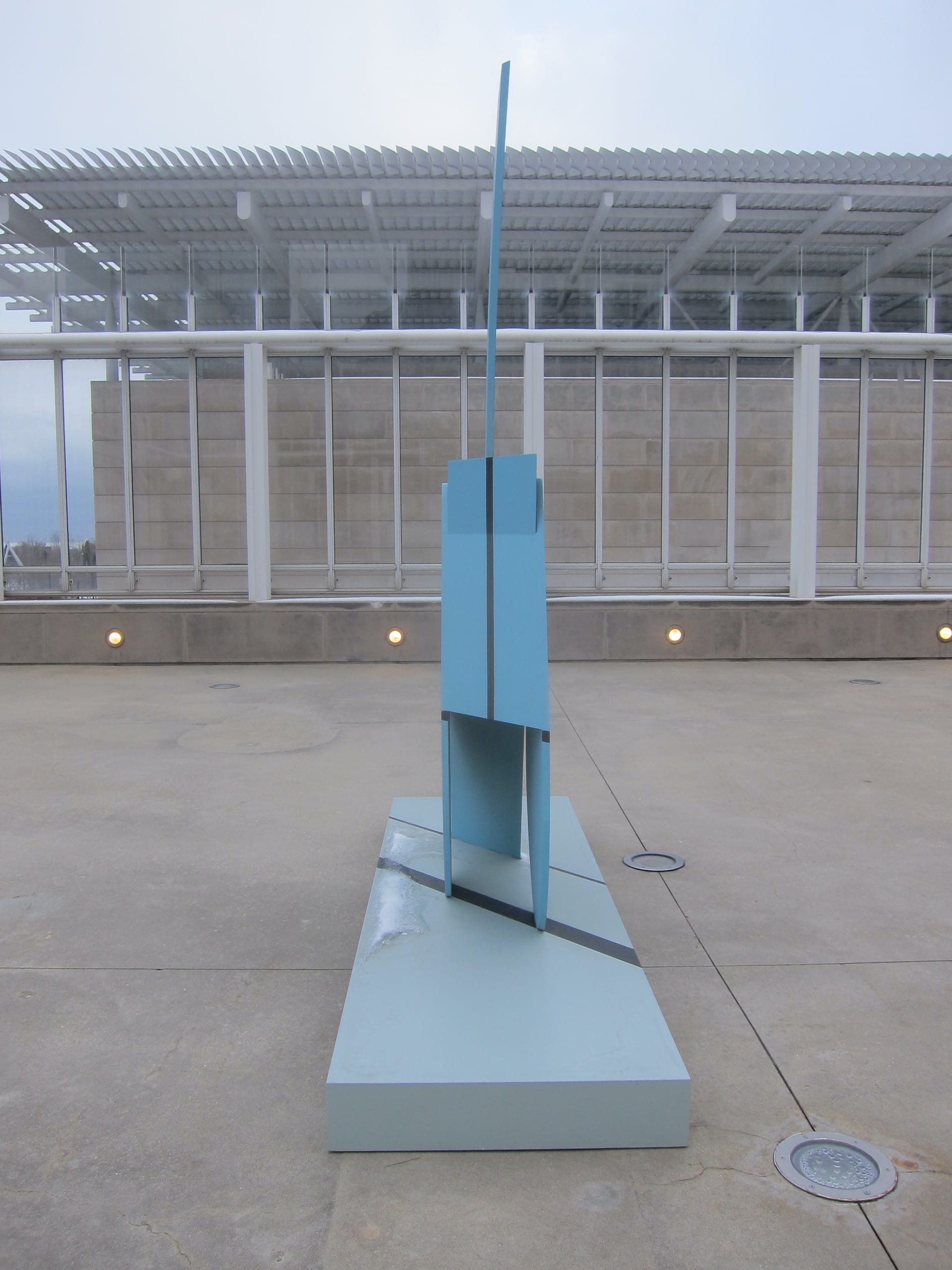

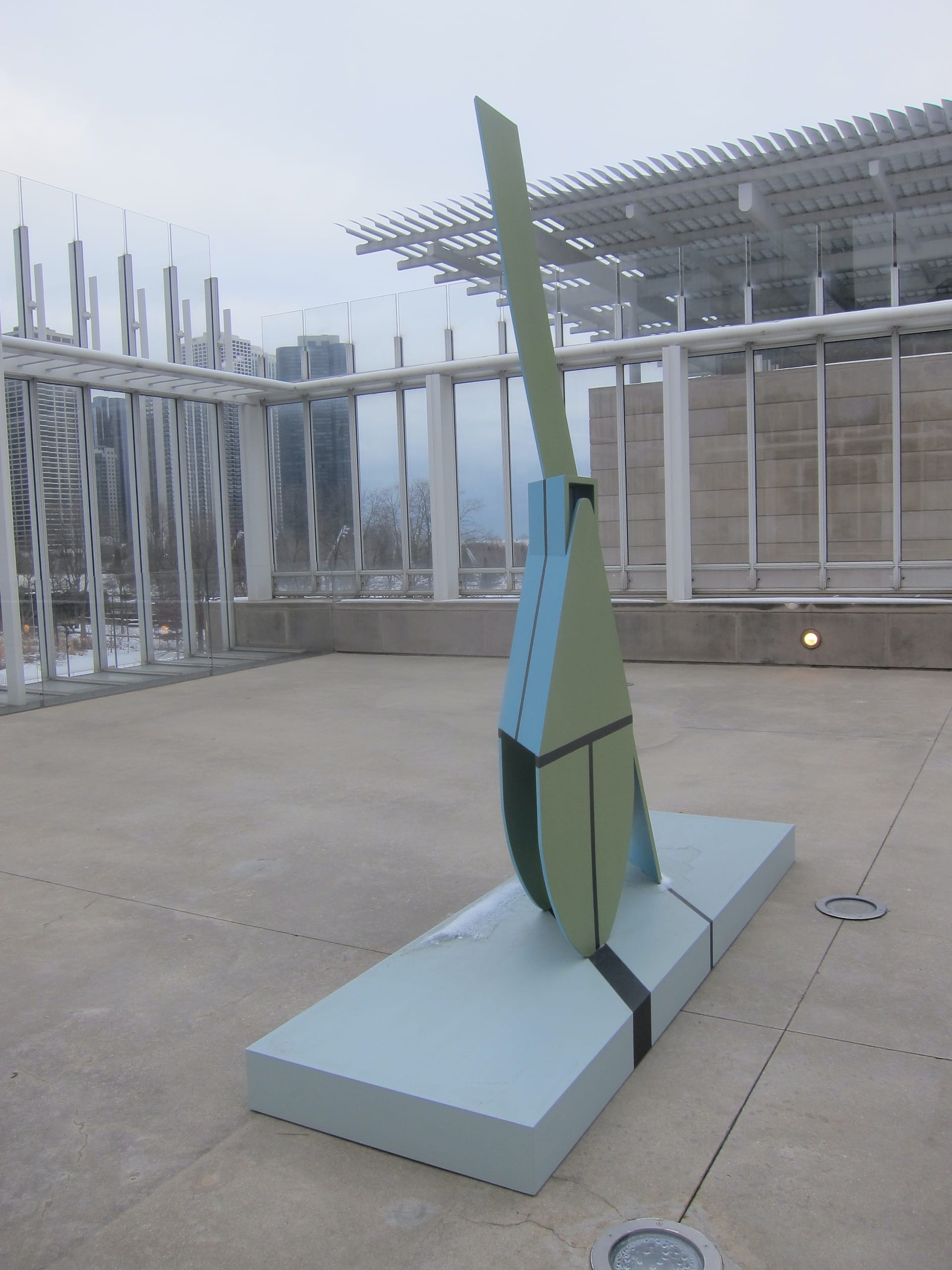

Multiple views of Diane Simpson, "Rocket Launcher" (2025), acrylic-painted MDF (photos Lori Waxman/Hyperallergic)

Born in 1935 in Joliet, a small city on the outskirts of Chicago, Simpson has been at this for a long time. Is she having a moment? Sort of, at least relative to her age — 90 — and the career’s worth of milestones she’s achieved in the past decade or so: Her first inclusion in the Whitney Biennial, first retrospective, first international shows, first museum solo shows, first outdoor commission, first multi-gallery representation. Before that, Simpson exhibited primarily in Chicago, more or less frequently, depending on trends and connections and luck, good and bad. Her longevity has more than made up for her late start (she delayed the completion of her BFA at the School of the Art Institute for 10 years and three children). While her peers’ MFA studios were downtown, hers was in the dining room of her family’s home in Wilmette, a suburb north of Chicago. That’s where she first began to experiment with large sheets of corrugated cardboard, easy to pack flat and transport into the city, then assemble out of interlocking planes. Those sculptures filled her first gallery show, held in 1979 at the women’s co-op Artemisia, and most were not seen again until her 2020 solo exhibition at Wesleyan University.

Simpson still lives and works in that suburban house, her art spread out through the attic, garage, spare bedroom, and basement. Her late husband, Ken, a pioneering medical ethicist and all-around champion of his wife’s art practice, made her studio tables, lunch, and much else. Now her grandsons do the installation. Artists need all kinds of support to succeed professionally, from the emotional to the administrative; most often, it’s been men who’ve had it in the form of their spouses. Over the course of her career, Diane Simpson flipped more than just two and three dimensions.

Multiple views of Diane Simpson, "Neckline - extended" (2011), LDF, aluminum, enamel, colored pencil, on view at Corbett vs. Dempsey gallery, Chicago (photos Lori Waxman/Hyperallergic)

Multiple views of Diane Simpson, "Thinly Veiled" (1985), oil stain on MDF, fiberglass screening, pencil, on view at Corbett vs. Dempsey gallery, Chicago (photos Lori Waxman/Hyperallergic)

Simpson divides her oeuvre into multi-year series. Each grouping has a common starting point, from headgear to window dressing. After the initial drawings comes translation into three dimensions using an ever-evolving array of unexpected materials — which generally have zero connection to the original inspiration: linoleum, various types of wood, metal sheeting, meshes, copper tubing, leather, corrugated plastic, foam board, printed fabrics. Medium density fiberboard (MDF) is a longtime favorite. Fabricating everything fastidiously and from scratch, without assistants, out of components not designed to do what she asks of them, has resulted in years of inventiveness. Her joints are especially clever, accomplished through rivets, lacing, wrapping, and interlocking. Curvatures are achieved by scoring and bending, or, as in a roll-top desk, by affixing bands of a hard material to textile backing.

In a group show at Corbett vs. Dempsey, Simpson has two neutral-toned sculptures that bear this all out delightfully. “Thinly Veiled” (1985) belongs to a series inspired by historical European dress, including a man’s pantaloon and cape circa 1562 and a whalebone underskirt, or “pannier,” of about 1750. From a certain angle, “Thinly Veiled” echoes the form of a woman’s head covering, but to me it mostly reads as a model for a tropical apartment building, ship-like, with plentiful halfmoon balconies swathed in mosquito netting. Architecture studios used to present their proposals like this, out of light brown MDF, on a simple base, with pencilled-in details and tacked on fiberglass screening. “Neckline – extended” (2011), part of a grouping devoted to bibs, vests, collars, and tunics, stands seven feet tall and cascades like a hard waterfall down a series of thin ledges. Back up far enough and squint, and those aluminum ledges become the silhouette of a neck and shoulders, the beige LDF waterfall a high collar connected to a plunging V-neck. From the side, what it is is anyone’s guess. From behind, I spy a curio shelf with curved brackets and, above it, a shelf holding an upright open book.

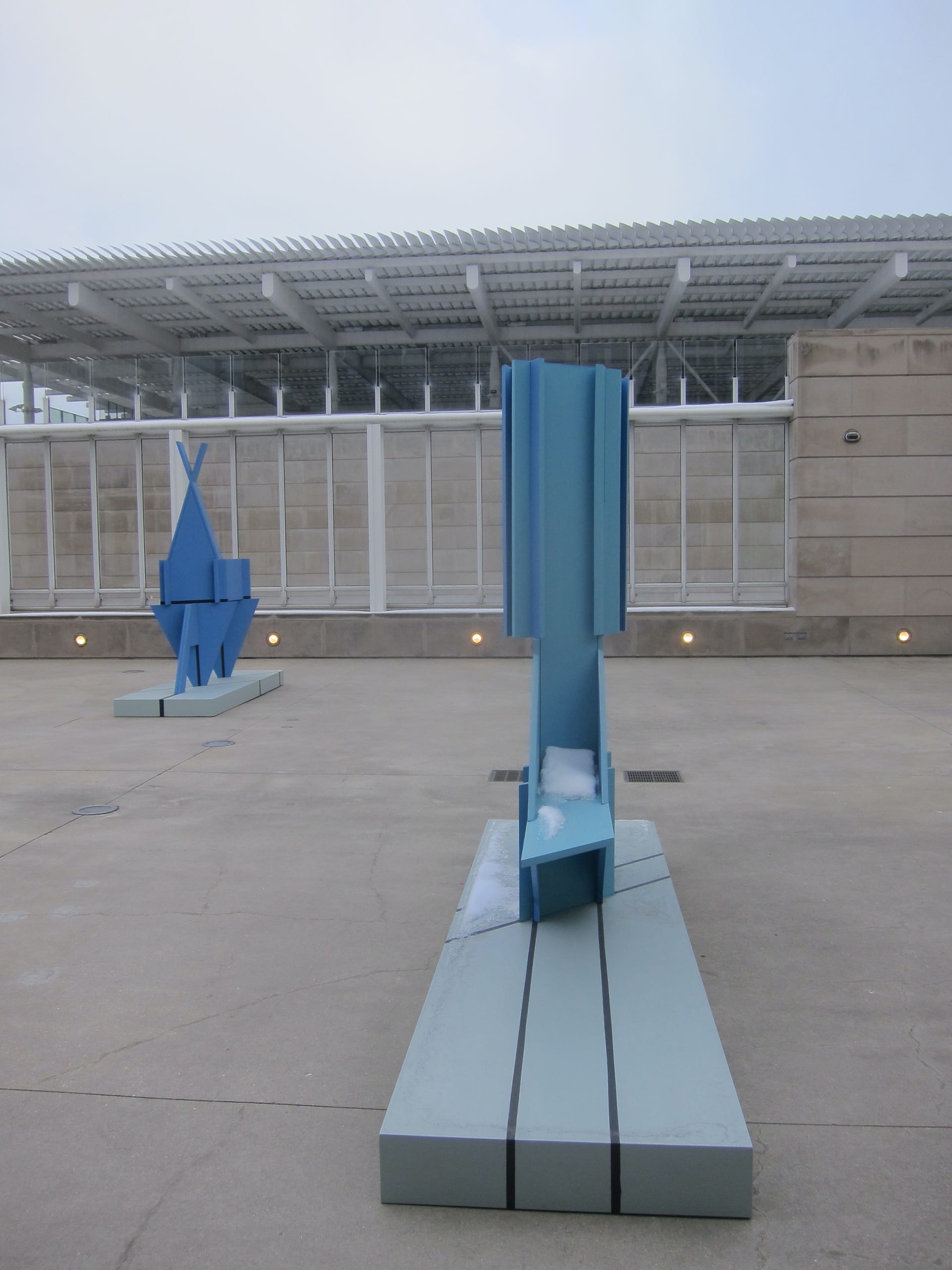

Multiple views of Diane Simpson, "Grenade" (2025), acrylic-painted MDF (photos Lori Waxman/Hyperallergic) (photos Lori Waxman/Hyperallergic)

Note that the outline of neck and shoulders does not define a person, but a garment. Likewise, under that veil is empty space. Simpson, for all her interest in clothing, never includes bodies. Think exoskeleton, the thing that shapes a body, and not the other way around. From there it’s not a far leap to her latest work, devoted to the applied arts of furniture and architectural detailing. Good for Future, her exhibit of three new commissions on the roof of the Art Institute, belongs to this set. The irresistible title was a note-to-self Simpson wrote in the 1980s on a roll of drawings of unrealized sculptures. Here they are now, in alternating shades of periwinkle, sky blue, and olive, doing many of the things her artworks always do, plus a few novelties. The newest is being made with the help of an assistant, due to the heaviness of exterior-grade MDF. The bases have a fresh treatment, painted with black lines that coordinate with their skewed planes, like the graph paper of her preparatory drawings.

Set outdoors against the Chicago skyline, the work invites comparison with a century and a half of high-rises, whose forms reverberate in Simpson’s, at least from certain angles. From others, I glimpse a giant perfume bottle, a seesaw, a Japanese roofline, and maybe an elephant. Also: a monumental grenade, a rocket launcher, and a fortress. Good for Future feels just right for 2026.

Brian Calvin, Maureen Gallace, Diane Simpson continues at Corbett vs. Dempsey (2156 West Fulton Street, Chicago, Illinois) through February 28. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.

Diane Simpson: “Good for Future” continues on the Bluhm Family Terrace of the Art Institute of Chicago (159 East Monroe Street, Chicago, Illinois) through April 19. The exhibition was organized by AIC assistant curator Makayla May.