Uncovering the Secrets of Henri Rousseau’s Paintings

A new exhibition freshly contextualizes many artworks in the light of his personal story, while conservators conducted revelatory technical studies.

PHILADELPHIA — If you’ve ever tried to puzzle out what’s happening in Henri Rousseau’s haunting “Sleeping Gypsy” (1897) at the Museum of Modern Art, then you’re already familiar with the artist’s extraordinary ability to tantalize viewers. That painting of a lion and a slumbering woman is on view in Henri Rousseau: A Painter’s Secrets at the Barnes Foundation, now in the company of nearly 60 more works — many equally mesmerizing.

Self-taught, self-confident, and inscrutable, Henri Rousseau was "a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma," to crib Winston Churchill’s famous characterization of Russia. He began painting before retiring as a toll collector for the city of Paris in 1893. It was at this point that he became a professional, though impoverished, artist.

The title A Painter’s Secrets is not a ploy. Curators Christopher Green and Nancy Ireson freshly contextualized many artworks in the light of his personal story, and conservators conducted revelatory technical studies that, among other findings, exposed areas of long obscured, nuanced color. The grumpy-faced baby in “The Family” (c. 1892–1900) is enlarged in the catalog to underscore Rousseau’s shrewd observational skills.

Visitors with a deerstalker mindset may experience frissons of amazement when scrutinizing the paintings in the galleries. It’s startling to discover the top section of the four-year-old Eiffel Tower in the distant background of “Sawmill, Outskirts of Paris” (1893–95), one of the small works that the enterprising painter sold to his neighbors. Other surprises are eerie. Sheltered within a barely visible structure in “Carnival Evening” (1886), a disembodied head spies on a pair of costumed revelers.

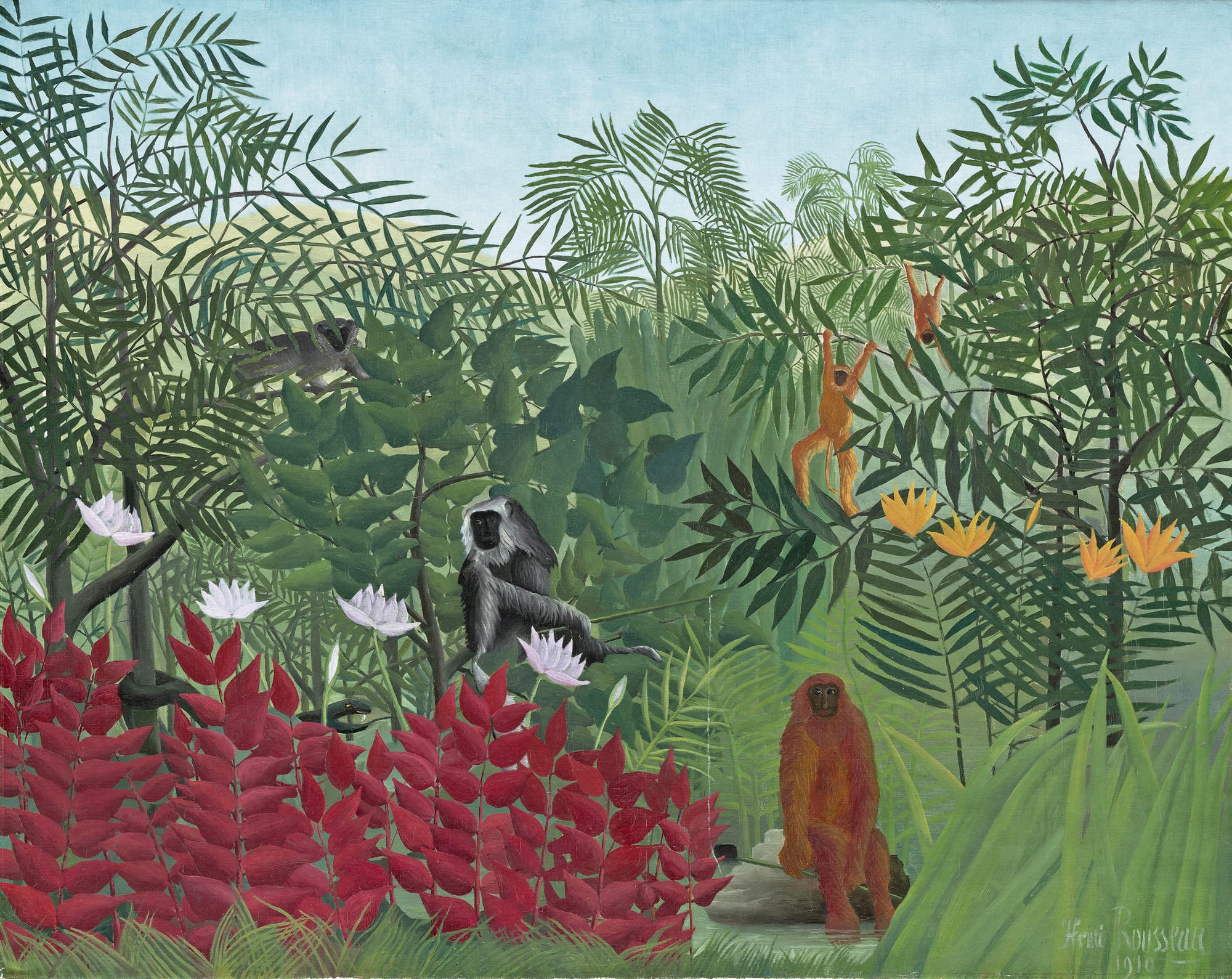

A Painter’s Secrets incorporates several of the Barnes Foundation's 18 Rousseau paintings, temporarily installed alongside loans of thematically related examples. Visitors can compare their “Scouts Attacked by a Tiger” (1904) with the savage animals in dramatic struggles depicted in the Fondation Beyeler’s “The Hungry Lion Throws Itself Upon the Antelope” (1898–1905) and the Cleveland Museum of Art’s “Fight Between a Tiger and a Buffalo” (1908). The three masterworks also share a bounty of exquisitely rendered foliage inspired by the displays of exotic plants in Paris’s botanical gardens.

“Rousseau is not so much a storyteller as a story-giver,” Christopher Green notes in his catalog essay. Will the naked damsel with knee-length blond hair in the Barnes’s “Unpleasant Surprise” (1899–1901) be rescued by the hunter shooting at the ferocious bear about to maul her? Will the beautiful flute player in the Musée d'Orsay’s “The Snake Charmer” (1907) be able to keep the venomous serpents at bay? Green suggests that Rousseau’s fondness for unresolved scenarios may explain why he became important to the Surrealists.

It was Rousseau’s fellow artists who initially recognized his genius. An ambitious painter, he courted official patronage in vain. Picasso, who both admired and gently mocked Rousseau, first discovered his work in 1908, when he came across the “Portrait of a Woman” (1895) in a bric-a-brac shop selling canvases for reuse. Framed on one side by voluptuously patterned, cinched drapery, his model stands on a balcony in front of an enfilade of potted flowers, overlooking a distant mountain range and a delicately colored sky. Unsurprisingly, Picasso bought it and kept it until his death. You’ll find it in A Painter’s Secrets, on loan from the Musée national Picasso-Paris.

If A Painter’s Secrets kindles your interest in Rousseau, peruse the exhibition’s weighty catalog. However, if you prefer to read up on the painter’s life and work in relation to the origins of the avant-garde in France prior to World War I, scare down a copy of Roger Shattuck’s The Banquet Years (1961).

While you’re at the Barnes, you can find other works by Rousseau from the permanent collection in nearby galleries, installed unchanged since 1951 as components of founder Albert Barnes’s provocative art ensembles. Once you’re there, prepare to be sidetracked by the abundance of work by Picasso, Cézanne, Matisse, and Renoir. A Painter's Secrets is a rare opportunity to situate Rousseau in this lineage and, in the process, to absorb his innovative (and far from “naive”) use of pictorial space and color, and his enchanting imagination.

Henri Rousseau: A Painter's Secrets continues at the Barnes Foundation (2025 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) through February 22, 2026. The exhibition was curated by Christopher Green and Nancy Ireson, with the support of Juliette Degennes.

After the Barnes Foundation, the exhibition will travel to the Musée de l'Orangerie, Paris.