The Radiance of the French Renaissance in Miniature

While the grandest glories of the French Renaissance were the elaborate castles circling Paris and adorning the Loire Valley, down in Central France a much smaller art form flourished.

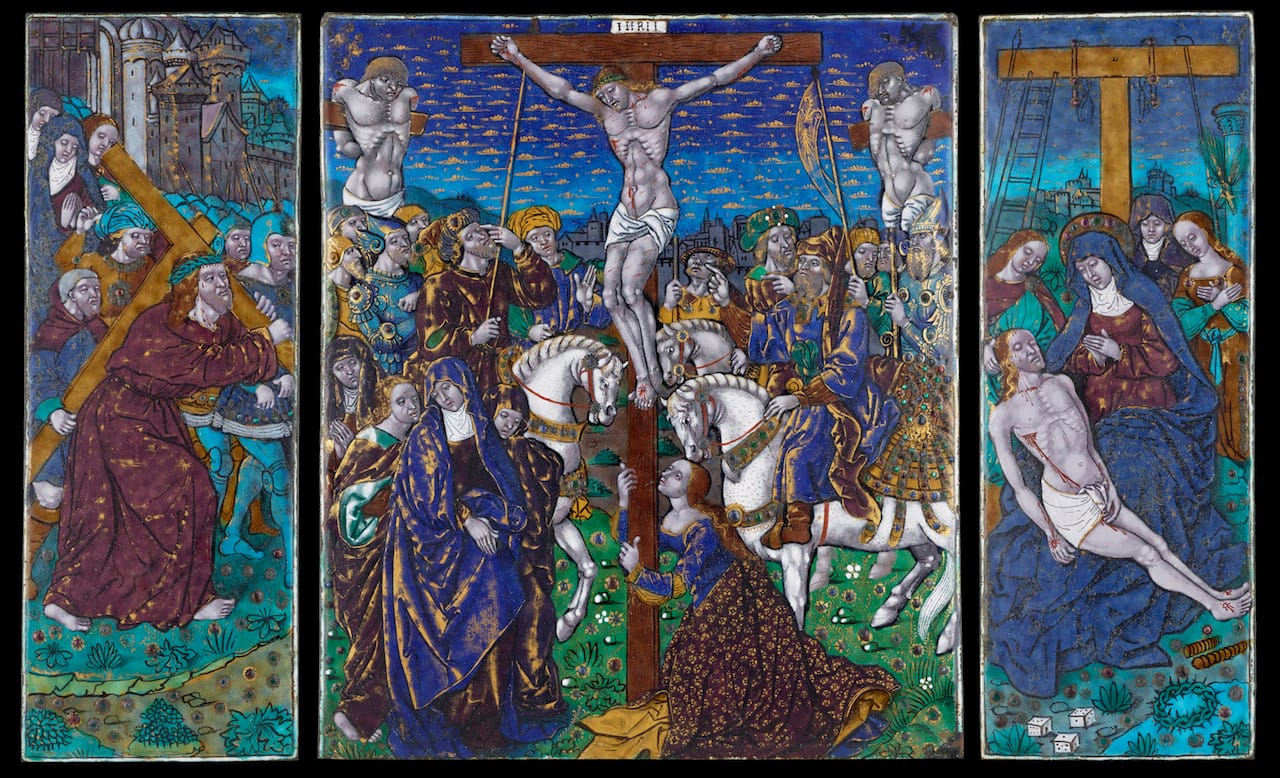

While the grandest glories of the French Renaissance were the elaborate castles circling Paris and adorning the Loire Valley, down in Central France a much smaller art form flourished. The enamels of Limoges involved a painstaking technique of fusing fine glass powder to a metal-based surface, a process that peaked in the 15th and 16th centuries. The industry later declined, then resurfaced in the 19th century, just in time for American collectors like Henry Clay Frick to take an obsessive interest in the following decades.

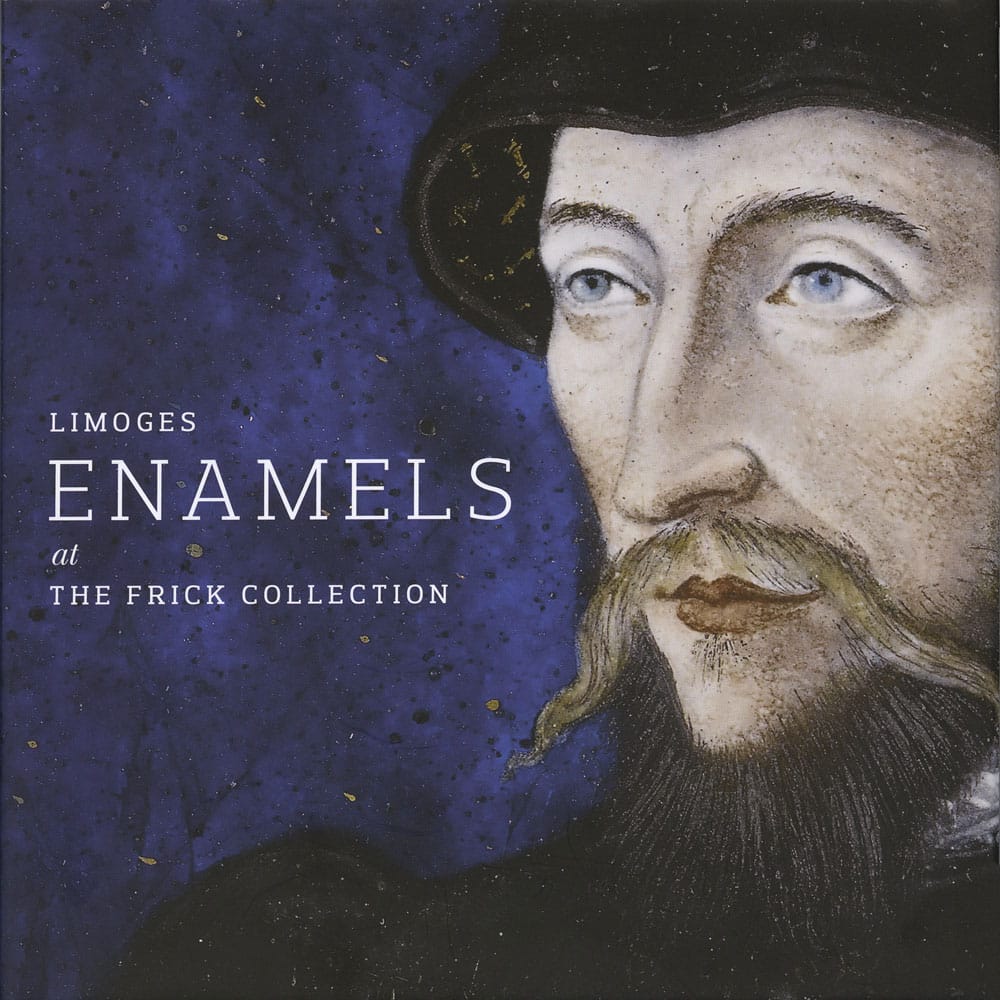

The Frick Collection recently released its first book on its enamels, Limoges Enamels at The Frick Collection, published in association with D Giles Limited. It’s intended for a lay enamel audience, and even if you’ve not so much as looked at a religious scene by the Master of the Large Foreheads, it’s an accessible introduction to enamel history.

Ian Wardropper, director of the Frick Collection, writes in his introduction:

The painted enamels of Limoges constitute one of the distinctive art forms of the French Renaissance, but their production remained largely regional. Much of what characterizes art of the period — such as the magnificent interiors of Fontainebleau, the architecture of Paris, and the royal chateaux — centers on the court in the Île-de-France and its outliers. Far from the circle of the king, enamelers in central France revived a local practice, refining and improving earlier methods

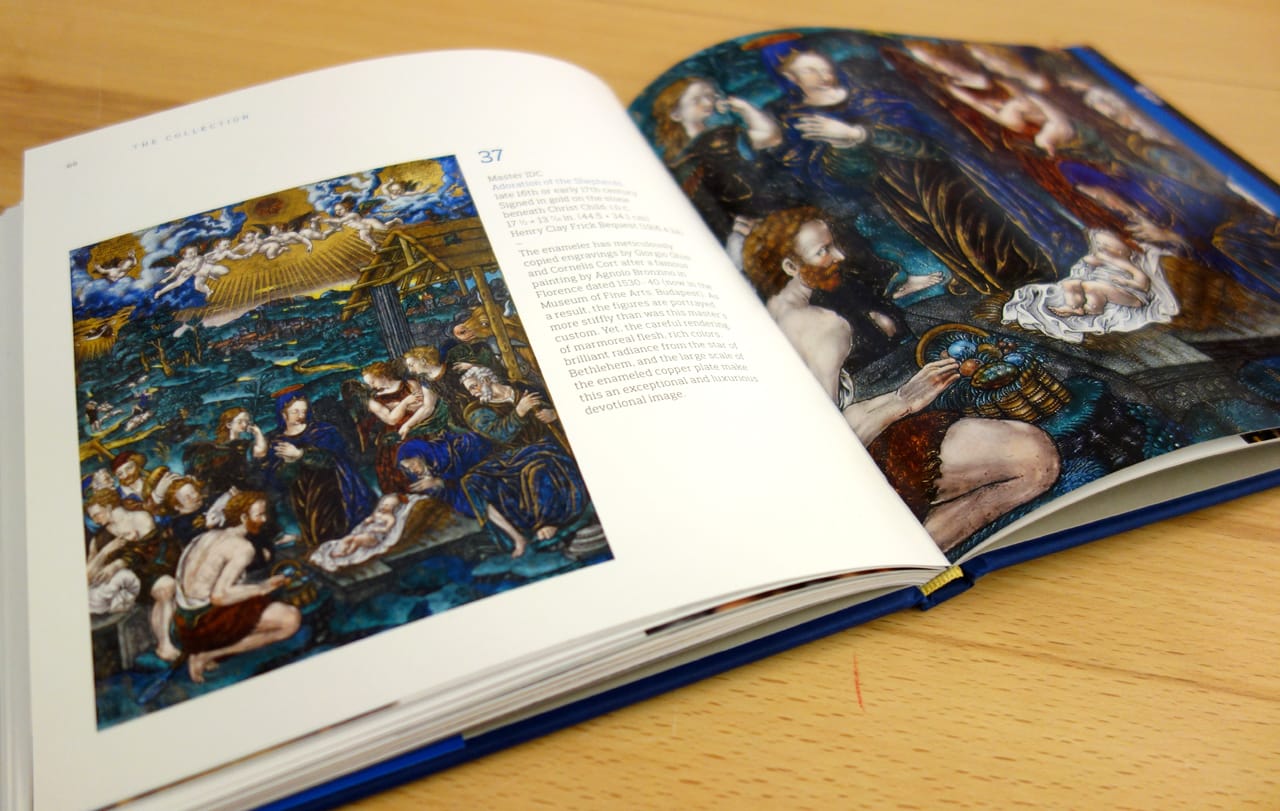

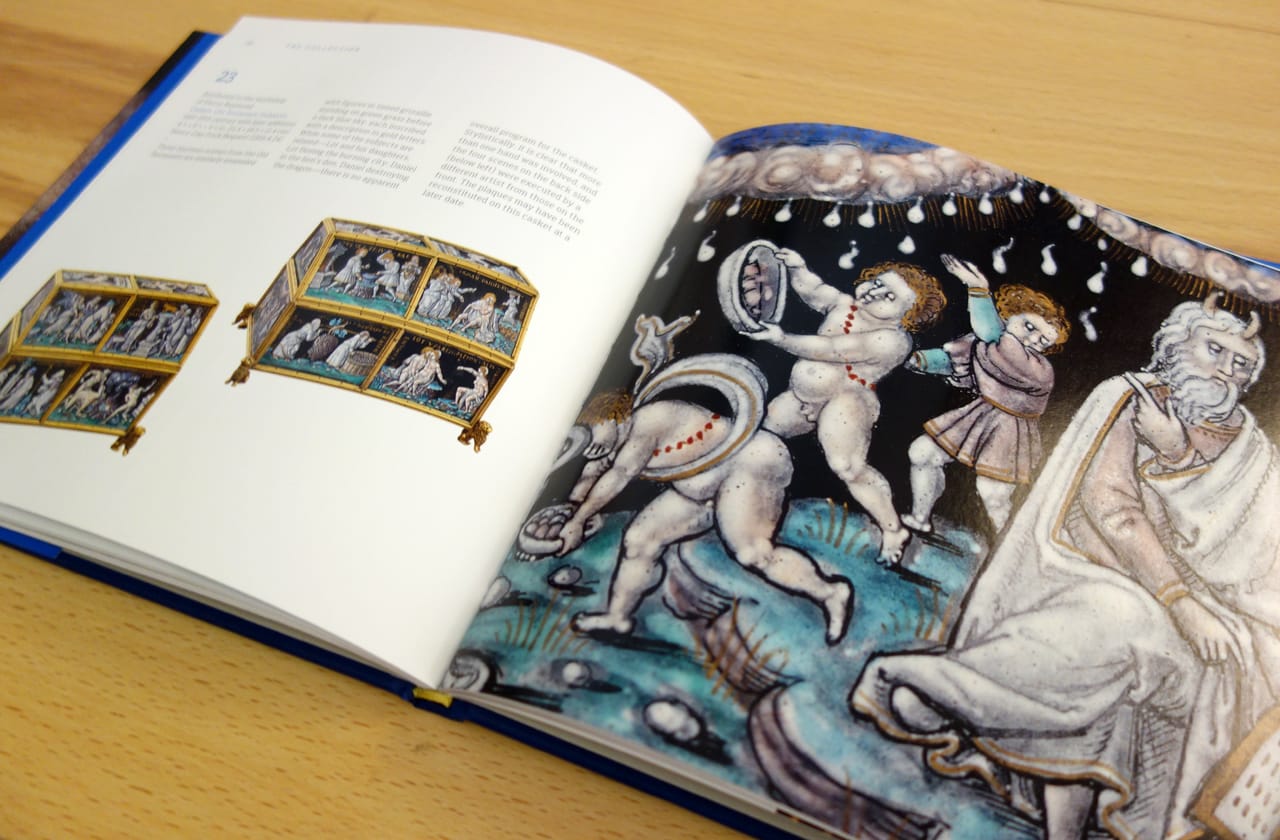

Limoges artisans focused on liturgical vessels and religious items in the Middle Ages, as the city was a point on pilgrimage routes to Italy and Spain. By the 16th century, like many Renaissance artists, they were dabbling as much in classical mythology as Christianity, and sometimes commissioned portraits. A late 16th-century oval dish by Jean Reymond has the Last Supper on one side, and Jupiter astride an eagle on the other. The imagery was often inspired or copied from other art forms, like small Book of Hours or Florentine paintings transmitted to France via printmaking.

The enamel artists were almost entirely men, but there is an interesting exception with Suzanne de Court, possibly the daughter of enamel maker Jean de Court. The book doesn’t touch on much of her back story, although it presents a beautiful pair of saltcellars from the late 16th or early 17th century with scenes from the life of Orpheus, which were created in her preferred deep colors of blue, emerald green, and turquoise embedded with gilded patterns.

The jewel-like luminescence of enamels didn’t attract Henry Clay Frick until he’d delved into decorative arts to accompany his Old Masters paintings. The enamels at the Frick, are housed in the recently reinstalled Enamels Room, and they were initially brought together by John Pierpont Morgan. Frick purchased the lot after Morgan’s death in 1913, and he was apparently so enthused by them that he gave up the personal office in his Fifth Avenue mansion for their display, and that’s where they remain today, a small, but important, collection revealing this delicate art tradition.

Limoges Enamels at The Frick Collection is out now from the Frick Collection in association with D Giles Limited.