Spotlighting the Contributions of Women to Modern Interior Design

The Museum of Modern Art explores modern interiors from the 1920s to '50s and the contributions of women to their architecture and design.

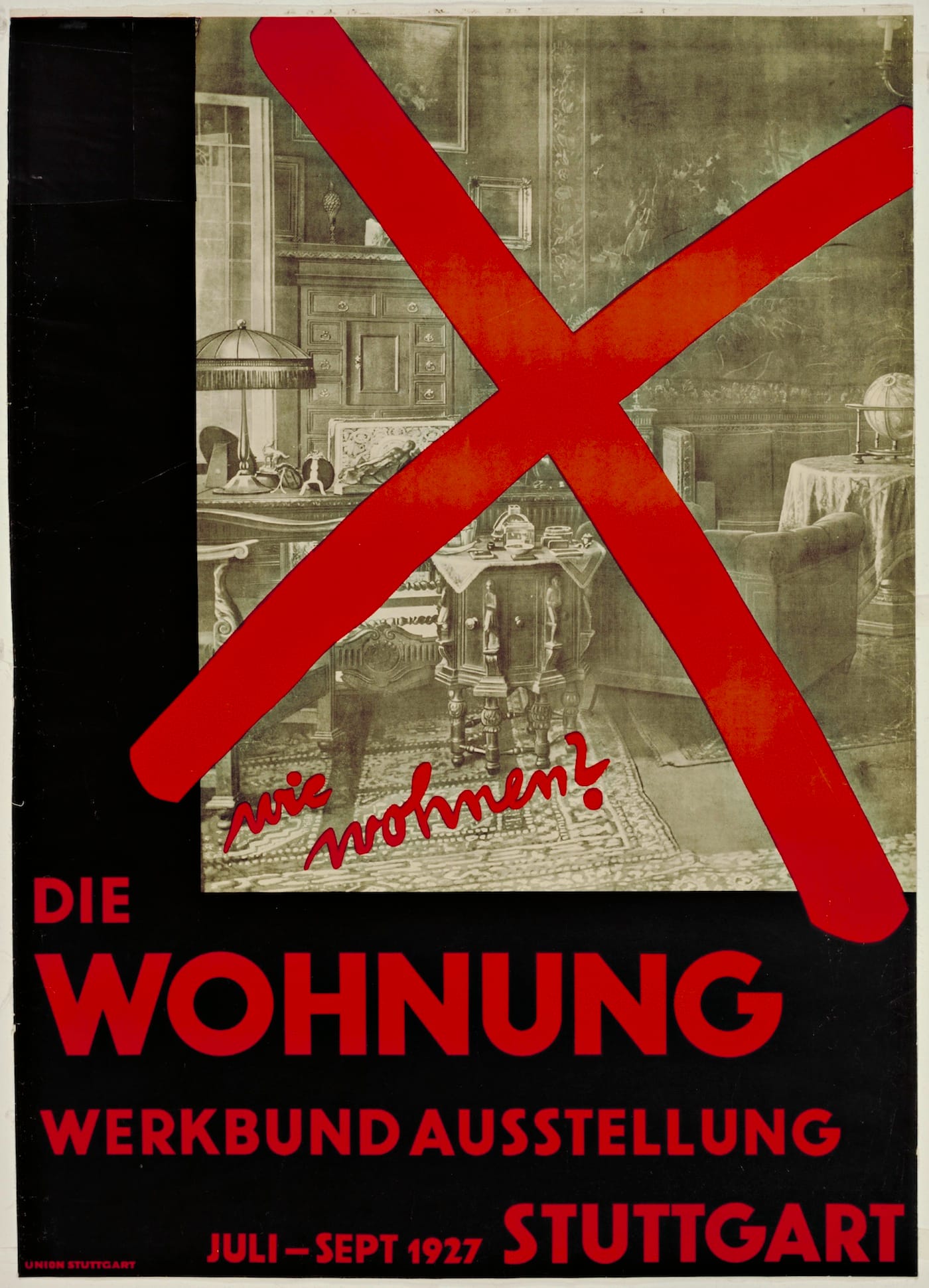

How Should We Live? Propositions for the Modern Interior at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) concentrates on the post-World War I period from the 1920s to 1950s, during which synthetic materials like tubular steel and plastic were incorporated into domestic design. The exhibition’s undercurrent is the contribution of women architects and designers to this era. Recent acquisitions on view include furniture by Eileen Gray, who explored fluid functionality at the 1929 E-1027 house in the South of France, and Grete Schütte-Lihotzky’s 1926–27 Frankfurt Kitchen with its prefabricated parts envisioned for postwar affordable housing. The kitchen is now MoMA’s earliest work by a woman architect.

The exhibition, organized by MoMA curator Juliet Kinchin with curatorial assistant Luke Baker, follows similar investigations into modern living at the museum, such as Endless House: Intersections of Art and Architecture that closed earlier this year. How Should We Live? is a bit more ambitious in its layout, including installations or evocations of historic interiors, as well as a tribute to the 1927 Velvet and Silk Café by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich. There, visitors can lounge on reproductions of the cantilevered tubular steel and black leather chairs, and enjoy a coffee before a large window overlooking the sculpture garden. Presented by Mies and Reich at the “Die Mode der Dame” (Women’s fashion) exhibition in Weimar-era Berlin, it was for many 1920s visitors their first tactile interaction with these modern designs.

After exploring the exhibition, I did wish that it had concentrated more fully on these early 20th-century women like Reich, Gray, and Schütte-Lihotzky, as their work, and the challenges of women working in architecture at this time, are definitely worthy of deeper investigation. For instance, the label text notes that designer Charlotte Perriand — who proclaimed in 1929 “METAL plays the same part in furniture as cement does in architecture. IT IS A REVOLUTION” — was highly involved in tubular steel furniture, which she made with Le Corbusier and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret.

However, Le Corbusier initially dismissed her with the snide “we don’t embroider cushions here,” despite his obvious appreciation for her skills. Her attention to functional detail is visible in a recreated space from the 1959 Maison du Brésil at the Cité Universitaire in Paris, where Perriand’s deft room divider incorporates a reading lamp, shelves, a wardrobe, and storage.

Many of the women represented in How Should We Live? were often overshadowed in their collaborations with more prominent men. Ray Eames experimented on molded plywood designs with Charles Eames; Florence Knoll guided much of the success of Knoll Associates as a business partner with her husband Hans Knoll; and Noémi Raymond worked with her husband Antonin Raymond to fuse Japanese influences with European and American aesthetics.

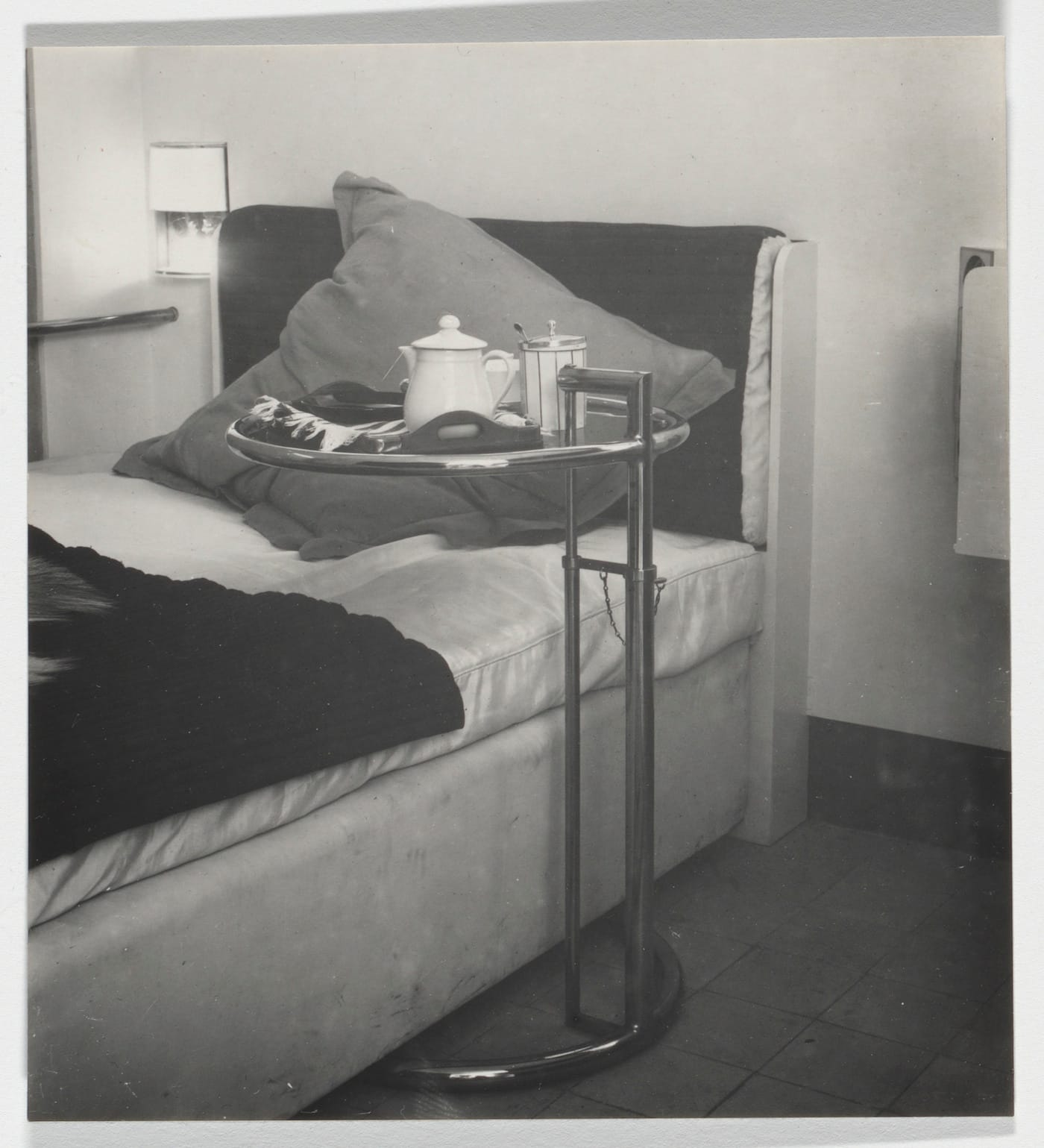

Although some of the stagings of modern interiors in the exhibition involve only a few pieces of furniture, they do suggest the depth of MoMA’s interior holdings, which aren’t frequently on view in the space-strapped museum. Yet how people lived with design is so integral to the museum’s identity, going back to Philip Johnson. Following a visit to a 1927 exhibition by Mies and Reich in Germany, he invited the couple to design his New York apartment in 1930, when he was just beginning his role as MoMA’s founding director in the department of architecture. The austere navy curtains, and tubular bed from this design are featured in How Should We Live?, offering their minimal, elegant answer to that question.

How Should We Live? Propositions for the Modern Interior continues at the Museum of Modern Art (11 West 53rd Street, Midtown West, Manhattan) through April 23, 2017.