Deborah Jack’s Immersive Elegy for Water

The artist critiques the legitimacy of cartography, empire, and ecological adaptation.

DENVER — In the language of climate, water is dialectical: It is overabundance and scarcity; needed as well as dreaded. Psychologically, it can represent the unconscious, the maternal, the prelapsarian. Artist Deborah Jack disrupts any viewer’s impulse to find recreational soothing in the ocean’s tidal landscape, as she openly critiques the legitimacy of cartography, empire, and ecological adaptation.

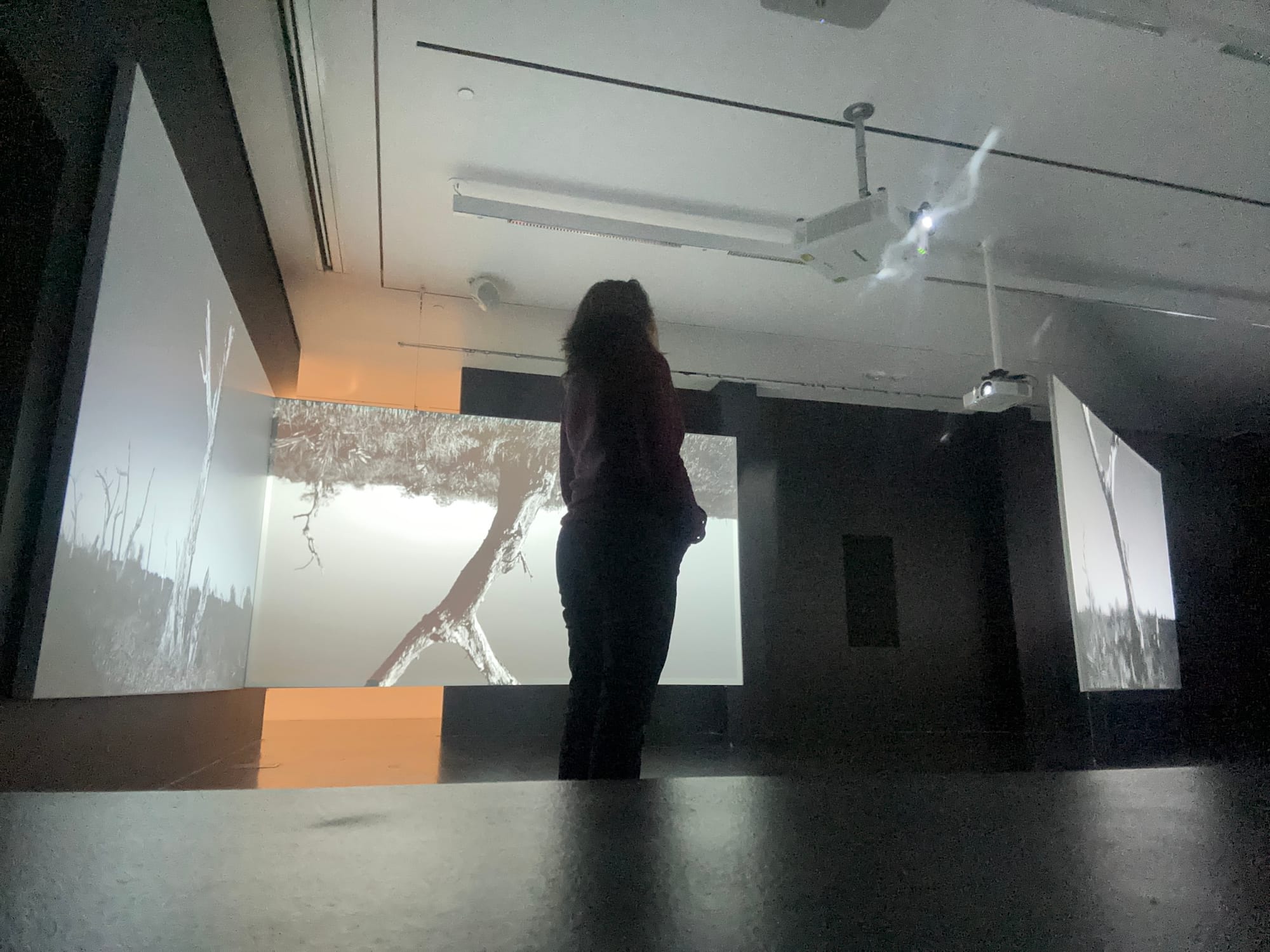

Jack's six-channel video installation "a sea desalts, creeping in the collapse... in the expanse...a rhizome looks for reason... whispers an elegy instead" (2024) — commissioned for Prospect.6 in New Orleans — comprises her current exhibition, the haunting of estuaries...an (after)math of confluence, at Denver's Museum of Contemporary Art. In it approaches water as both climate emergency and colonial oversight.

Estuaries are partially enclosed bodies of water in which freshwater from rivers and streams mixes with the ocean’s salt water. They form ecotones, where different ecosystems overlap — an in-between space that shrinks and expands with changing weather conditions.

The installation is organized as two sets of adjacent screens and two single-channel screens, the latter abutting in the center of the room. They depict scenes from coastal Maine, Brazil, St. Maarten, and Louisiana, inviting us to contemplate the visuals while complicating that process. The musical score, by the Diaphanous Ensemble, is a sonorously haunting accompaniment, full of minor chords, low notes, and high-pitched screes. Given that the ecotones Jack explores include the Atlantic, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Mississippi River, the thick, humid air on the day I visited also felt like a necessary invisible companion.

The structure of multi-channel video installations forces viewers to self-edit, focusing energy in one or two places at the limits of peripheral vision, and recognizing that absorbing everything in one go is not an option. Jack's imagery shifts between film and slide show, with smaller black and white images superimposed on the moving video — for instance, a black and white square of shoreline placed flatly on top of verdant island vegetation swaying with the wind. Other disorientating touches include juxtaposing video of churning brackish ocean water in saturated browns and blues with a stark black and white pan through a clearing of mangrove trees, halting to focus on a single trunk, from the base to the lopped-off top. On one of the adjoining screens, the imagery moves fast and chaotically; on the other, it’s slow and methodic.

In a 2021 interview, Jack noted that “Salt was the main industry in St. Maarten for many years. It can corrode and can preserve at the same time. You have to be the salt and choose what role you want to play. Do you want to corrode or preserve?” It is a pointed and timely question — whether one lives by the shore, where water is terrifyingly plentiful, or resides, as I do, in a landlocked interior, where it is a fast-vanishing, life-sustaining resource. Jack alludes to both of those roles: She lays bare the corrosion that human-made climate change creates in these coastal ecotones, and preserves this reality as an elegy in moving pictures.

As deadly, billion-dollar weather disasters become more frequent, art focused on climate effects may come to be the most reliable bellwether of these experiences and their consequences. The National Science Foundation, under the direction of the Trump administration, is currently seeking to dismantle the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, which supplies research and modeling information that aids in mitigating these risks. Without it, we may only know what’s coming by looking out the window, at the sky and the sea.

Deborah Jack: the haunting of estuaries...an (after)math of confluence continues at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver (1485 Delgany Street, Denver, Colorado) through February 15. The exhibition was curated by Miranda Lash.