Wooden mihrab from the shrine of Sayyida Ruqayya, Cairo, Egypt (1133): “Made by the order of the wife of the reigning Fatimid caliph, the mihrab is decorated on all sides, suggesting that it was intended as a freestanding structure. Sayyida Ruqayya was related to the Prophet Muhammad by marriage.” (© 2016 Eric Broug)

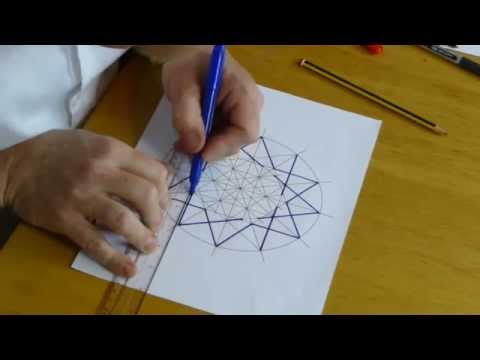

“The best way to learn about Islamic geometric design is to try it out for yourself,” writes Eric Broug in the Islamic Design Workbook, recently released by Thames & Hudson. Broug is behind the School of Islamic Geometric Design, and believes that learning to draw the striking patterns of mosques, kasbahs, mausoleums, and madrasas encourages a better appreciation of Islamic visual culture.

Cover of Islamic Design Workbook (courtesy Thames & Hudson)

Islamic Design Workbook could be written off as another example of the plague of adult coloring books. Although coloring is involved in the included worksheets, it’s more about engaging with the same problem solving as a 15th-century craftsperson, who would have employed just a compass and ruler to form these infinitely repeatable patterns. The 48 featured designs represent real places, often centuries-old, from India, Iran, Spain, Morocco, Iraq, Egypt, Turkey, and other countries with Islamic heritage.

“Every single geometric composition in Islamic art and architecture is created the same way, using a grid of construction lines,” Broug explains in an introduction. “Islamic geometric compositions also share another characteristic: they all have the same starting point — a circle.” That circle is then divided into parts, which are then used to create intersections that determine the rest of the pattern, which can continue limitlessly over a surface.

The fusion of mathematics with visual expression in these designs has had its influence on work outside Islamic art, such as M. C. Escher’s tessellations. And a tactile understanding of their careful planning and workmanship also reinforces the connection between the spiritual and the scientific in many of these structures. As Broug writes of experimenting with the designs, they will “reward you, every now and then, by revealing the harmony of geometry and symmetry.”

Pages from Islamic Design Workbook (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Pages from Islamic Design Workbook (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Saffarin Madrasa, Fez, Morocco (1271): “Its name means the ‘madrasa of the metalworkers.’ Like other Marinid madrasas, it is richly decorated, although its student accommodation is unadorned. Its decorative theme is clearly inspired by the Alhambra Palace of the Nasrids in Granada, Spain.” (© 2016 Eric Broug)

Moroccan wooden ceiling: “Moroccan craftsmen use this particular design frequently when making large wooden ceilings. They typically use a full-size template that consists of triangular wedge representing one sixteenth of the ceiling. This is all they need to make the entire ceiling.” (© 2016 Eric Broug)

Patterned ceiling in Morocco (photo by Gregory Palmer/Flickr)

The Aqsunqur Mosque, Cairo, Egypt (1346-47): “Emir Aqsunqur is said to have personally supervised the construction of the mosque. It is not typical of the Mamluk mosques of the period and bears similarities to the Great Mosque of Tripoli, where Aqsunqur was governor before he moved to Cairo.” (© 2016 Eric Broug)

Aqsunqur Mosque in Cairo, as seen in 2016 (photo by yeowatzup/Flickr)

Ulugh Beg Madrasa, Bukhara, Uzbekistan (1417-21): “Ulugh Beg was Timur’s grandson and is known not only as a sultan, but also as an astronomer and mathematician. He built an observatory in Samarkand that was the finest and largest in the Islamic world.” (© 2016 Eric Broug)

Ulugh Beg Madrasa in Uzbekistan, as seen in 2015 (photo by Francisco Anzola/Flickr)

Islamic Design Workbook by Eric Broug is out now from Thames & Hudson.