Discovering the Women of Art Brut

In Vienna, a new exhibition showcases the ideas and accomplishments of self-taught female artists.

VIENNA — The collective consciousness can be unpredictable. Who could have foreseen that the struggle for LGBT rights, the still-young #MeToo movement’s fight against sexual harassment, and growing alarm over global climate change, among other forces, would combine, as they have recently, into a wake-up call for many Western, industrialized countries?

Even the art world, its penchant for certain kinds of decadence notwithstanding, has made efforts to clean house of reported sexual harassers, and, partly as a result, to rectify the ways in which its women have been treated and overlooked.

The art establishment’s current awareness of women’s status can trace its roots in part to the American art historian Linda Nochlin’s 1971 essay “Why Are There No Great Women Artists?”; that seminal feminist text detailed how, for generations, institutional attitudes and obstacles had prevented deserving female art-makers from being recognized in Western art history’s canon.

Set against this social and cultural backdrop — and the increasing sensitivity to it among the public and in the media — a big, new exhibition at the Bank Austria Kunstforum Wien is shining a spotlight on a remarkable group of the long overlooked among the long overlooked.

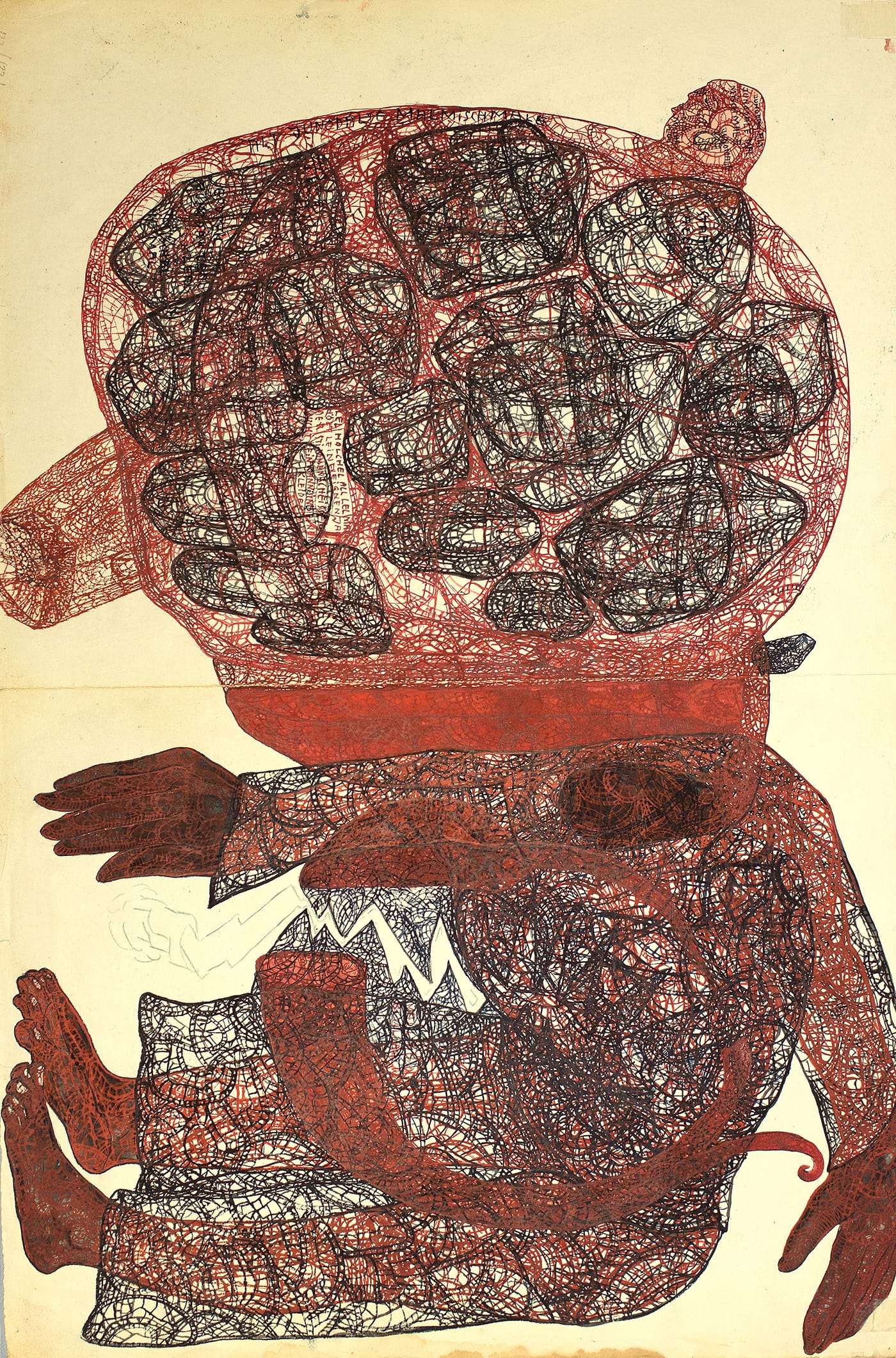

With Flying High: Women Artists of Art Brut, an international survey of more than 300 works, this art center in downtown Vienna is focusing on the accomplishments of 93 female self-taught art-makers. Forget about recognition from the cultural mainstream; many of the artists whose paintings, drawings, sculptures, and unclassifiable creations are gathered here have long been passed over or simply unknown — even in the specialized, overlapping fields of art brut and outsider art.

The words “Flying High,” alluding to the spirit of creative freedom found in these works, appear in English in both the German and the English versions of the exhibition’s title; that phrase also seems to suggest that a presentation of this magnitude may help its featured artists’ reputations to soar.

Co-organized by the Kunstforum Wien’s director, Ingried Brugger, and Hannah Rieger, a Vienna-based expert on art brut and outsider art who has amassed one of the most significant collections of these related genres in Europe, Flying High looks back chronologically at the history of the genre dubbed “art brut” (literally, “raw art”) by the French modern artist Jean Dubuffet in the 1940s. The term refers to the direct-from-the-heart creative impulse, unfiltered by theory, that can be felt in the works of self-taught visionaries situated by choice or by the force of circumstances on the margins of mainstream society and culture.

In tracing the history of this field, Flying High looks back at the work of pioneering European psychiatrists who became interested, often for diagnostic purposes, in the drawings and other creations of their patients at psychiatric hospitals, and places on center stage the art of women who were associated with such institutions.

Thus, the exhibition is broken up into historical-thematic sections looking at various works collected by the Swiss psychiatrist Walter Morgenthaler (1882-1965), whose most famous patient was the art brut creator Adolf Wölfli (1864-1930); and by the German art historian and psychiatrist Hans Prinzhorn at the University of Heidelberg’s psychiatric hospital in the early 1920s. Also on view are artworks personally collected by Dubuffet, who donated his holdings to what would become, in the mid-1970s, the Collection de l’Art Brut, in Lausanne, Switzerland, the world’s first museum dedicated to the creations of visionary autodidacts.

Another section of the exhibition looks at female artists’ works in the collection of L’Aracine, an association founded in France in the 1980s by the late Madeleine Lommel, primarily in response to Dubuffet’s gesture of largesse in neighboring Switzerland. Many years later, L’Aracine’s holdings were donated to the Lille Métropole Museum of Modern Art, Contemporary Art, and Art Brut in northern France, making that institution another key European center for the study and presentation of this kind of art. Flying High’s last section looks more generally at art brut works by women from around the world, from 1860 to today.

In an interview at the Kunstforum Wien just before the exhibition’s opening, Rieger said, “We were purists when it came to considering the criteria by which works were chosen for the show, but we were not so strict in the way they were hung.”

The collector-curator was referring to the fact that certain artists’ works appear in more than one section of the exhibition, given that some are to be found in more than one of the historical collections represented here. As it turns out, it is both enjoyable and informative to encounter drawings by the Swiss Aloïse Corbaz (1886–1964), or by the English Madge Gill (1882–1961), or yarn-covered, enigmatic objects by the American Judith Scott (1943–2005), in more than one spot as the exhibition unfolds, for they offer useful points of reference and comparison for some of the less familiar pieces on display, as well as the works of such non-Western artists as Guo Fengyi, from China, or Tae Takubo, from Japan.

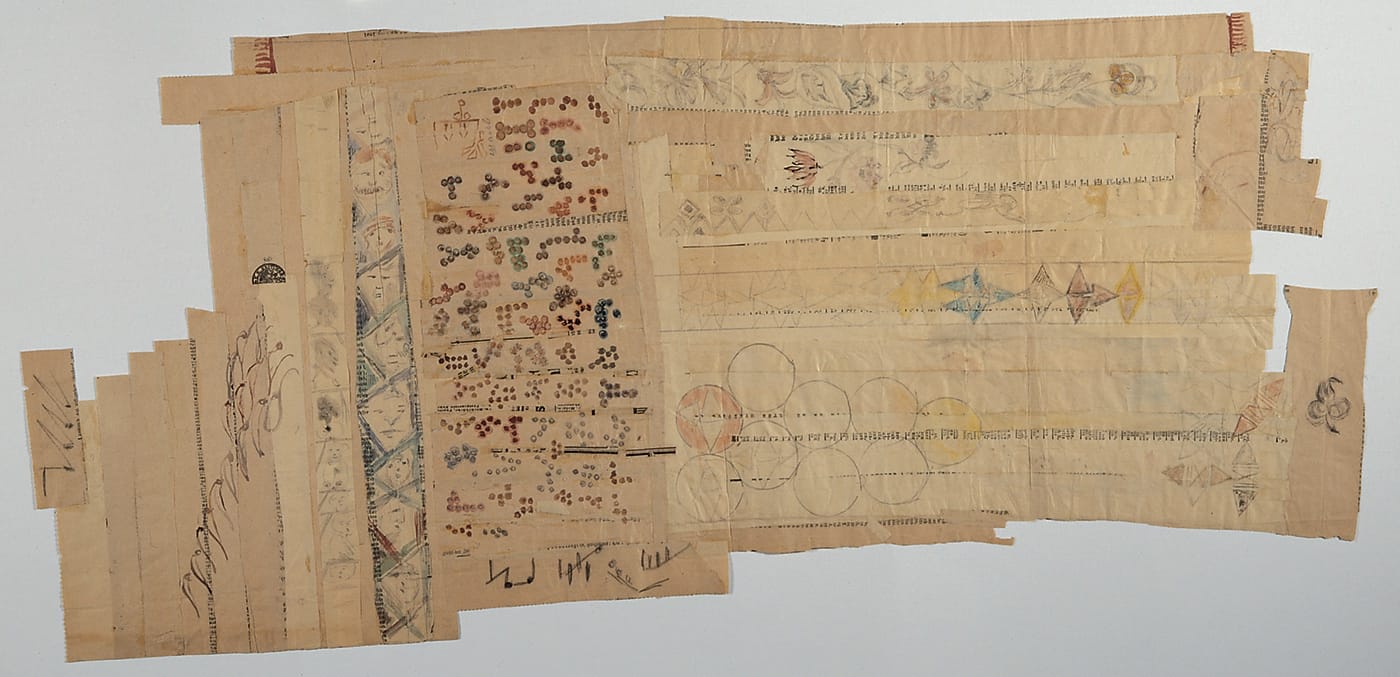

Visitors to the Kunstforum Wien first enter a high-ceilinged room in which the show’s unmistakable anchor piece is on view in a specially constructed vitrine — the nearly 46-foot-long, multi-part drawing “Le Cloisonné de théâtre” (1950–51), in colored pencil on pieced-together sheets of paper, by Corbaz.

One of the definitive art brut makers whose works Dubuffet began collecting during his first prospecting trips to Switzerland in the 1940s, Corbaz had served as a governess at the court of the German emperor Wilhelm II in the early 1900s. After her return to her homeland around the start of World War I, Corbaz was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Many of the boldly colored drawings she went on to make depict handsome German soldiers in their uniforms, while others give visible form to her romantic fantasies regarding the Kaiser.

Flying High also features works by such less well-known talents as the Austrian-born Ida Maly (1894–1941), who studied art and worked as an actress in Germany before being committed to a psychiatric hospital in 1928. She was killed in the Nazis’ euthanasia program. Little is known about her later life, but her mysterious, psychologically intense, fine-lined drawings penetrate their subjects’ faces and bodies like X-rays.

Among numerous pieces from the Prinzhorn Collection, the show includes a tray with a pitcher and a tiny watering can, all made of knotted and crocheted cotton yarn by the German-born Hedwig Wilms (1874–1915), who was diagnosed with, among other ailments, “menstrual psychosis.” Elsewhere, what appears to be a specimen of traditional “women’s work” turns out to be a rather modernist-feeling collage, made of strips of newspapers dated 1890 and 1891, by the Austrian-born artist known only as “Frau St.” (“Ms. St.”). Her creations were preserved thanks to the intervention of an interested professor who sent them to the Prinzhorn Collection in Heidelberg.

Some of the most unexpected works on view include the mixed-media, anatomically accurate dinosaur sculptures of the German artist Julia Krause-Harder (born 1973) and the circular-form abstractions in oil pastel and pencil on paper by the Austrian Sigrid Reingruber (born 1980), which bring to mind featureless faces or strange fruits.

As it turns out, coincidentally, Flying High is being presented at the same time as Vienna’s Lower Belvedere Museum is offering City of Women: Female Artists in Vienna from 1900 to 1938, an exhibition showcasing another group of contributions by women to various modern-art movements of the early 20th century.

“It’s the right moment,” the collector and exhibition co-curator Hannah Rieger pointed out, “but the truth is, when we started planning Flying High a few years ago, we had no idea that the status of women would become such a hot topic in society and in the news.”

Noting that initial reactions to the big show in Austria’s mass media have been very positive, she added, “For women in film, business, science, government, and culture to be recognized and appreciated — that really is great. For the women of art brut to earn this kind of attention — it’s a miracle!”

Flying High: Women Artists of Art Brut, curated by Ingried Brugger (Bank Austria Kunstforum Wien) & Hannah Rieger, continues at Bank Austria Kunstforum Wien (Freyung 8, Vienna, Austria) through June 23.

City of Women: Female Artists in Vienna from 1900 to 1938, curated by Sabine Fellner continues at at the Belvedere Museum (Prinz Eugen-Straße 27, Vienna) through May 19.